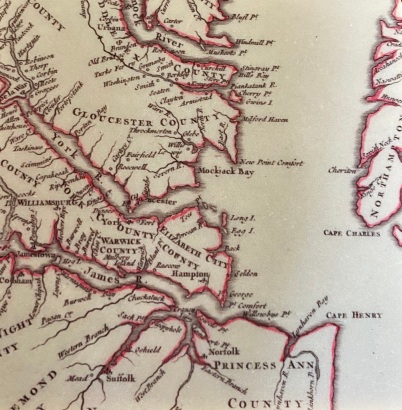

The first known mention of Francis Yeardley in Lower Norfolk County (later named Princess Anne, then Virginia Beach) was in June 1647. As noted in the prior post, Francis and his older brother Argoll, sons of Gov. George Yeardley, had settled in Accomack (later called Northampton County) on the Eastern Shore (Chesapeake Penninsula). Argoll had inherited their father’s lands, been appointed to the Governor’s Council, married, avoided the plague, and was enjoying a prosperous life. While Francis had acquired 3,000 acres by transporting 60 headrights, he was still a bachelor and not as successful as his brother. (See Interwoven Lives: Part I)

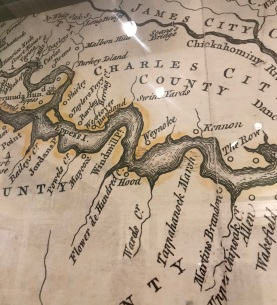

Eastern Shore and Lower Norfolk residents often shared merchant ties and attitudes from their common “outlier” status in the Virginia Colony. As the Thorowgood’s Lower Norfolk lands were close to Cape Henry at the entrance to the Chesapeake Bay, there would have been much shipping passing by, and it was a straight path from Hungars and Nassawadox Creek where the Yeardleys lived to the Thorowgood lands on the Lynnhaven Bay/River. So whether Francis came there for business or was looking for additional land and opportunities, he and several local acquaintances spent the night of June 10, 1647 at the house of the twice widowed Sarah Thorowgood Gookin.

Eastern Shore and Lower Norfolk residents often shared merchant ties and attitudes from their common “outlier” status in the Virginia Colony. As the Thorowgood’s Lower Norfolk lands were close to Cape Henry at the entrance to the Chesapeake Bay, there would have been much shipping passing by, and it was a straight path from Hungars and Nassawadox Creek where the Yeardleys lived to the Thorowgood lands on the Lynnhaven Bay/River. So whether Francis came there for business or was looking for additional land and opportunities, he and several local acquaintances spent the night of June 10, 1647 at the house of the twice widowed Sarah Thorowgood Gookin.

An Unexpected Death

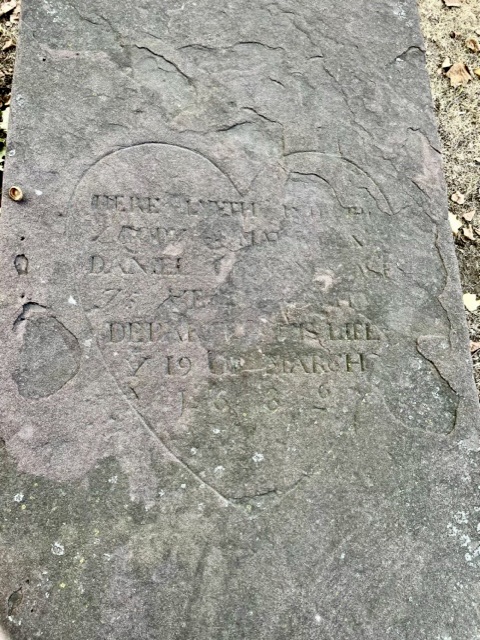

In a court deposition on June 12, Francis Yeardley stated, “Mr. Peregrine Bland being at the house of Mrs. Sarah Gookin in Lynhaven, broke his fast …in company of me and others and fed heartily…and drinking in the interim moderately…till his occasions calling him to go with Mr. Eyres and Mr. Hall, Chyrurgeon (surgeon).” Francis encouraged him to wait until the heat of the day had passed, but Bland proceeded on. Mr. Eyres went to check on him and discovered Bland had fallen asleep in a “barne fort” on the way. When Francis returned to check on him, he found Mr. Bland “lying on his right side, his arms under his head, dead, and purging at the mouth frothy blood.” From the inquest, it was determined there was no foul play, and, thus, their hostess, Sarah Gookin, was spared an appearance in court. [1]

Some have used this passage to conclude that Sarah ran a tavern on her property at which these gentlemen were staying. However, it was expected hospitality to provide food and shelter for travelers in those days, and these were notable guests. Licensed ordinaries (taverns) existed in Lower Norfolk County, and that very year the county court granted licenses to two individuals. None were to Sarah Gookin. [2]

Francis and Sarah had frequent involvement with the Lower Norfolk County Court over more than a decade, but there are no records of licensing, taxing, debts, sales, shipping, disputes, or gatherings for an ordinary connected with the Thorowgoods, Gookins, or Yeardleys . The existence of Gookin’s Landing and the building of a malt house (to produce malted beer) are evidence of smart businesses, but not proof of a tavern. The ceramics and artifacts found during the archaeological excavation of the Thorowgood’s original house site are expensive wares, not the type or quantity expected at a tavern site. Furthermore, all the sworn depositions from this incident clearly refer to the guests staying at Mrs. Gookin’s “house,” not another structure. (See Knives, Forks, and Silver Spoons: The Material Culture (and Jewels) of Sarah Offley Thorowgood Gookin Yeardley in 17th Century Virginia )

It was more than a century later during the Revolutionary era that there were references to a Pleasure House tavern in the Thorowgood area. It was even noted on a map when Benedict Arnold was commanding British troops in the area. That tavern burned in the War of 1812. [3]

An Unexpected Marriage

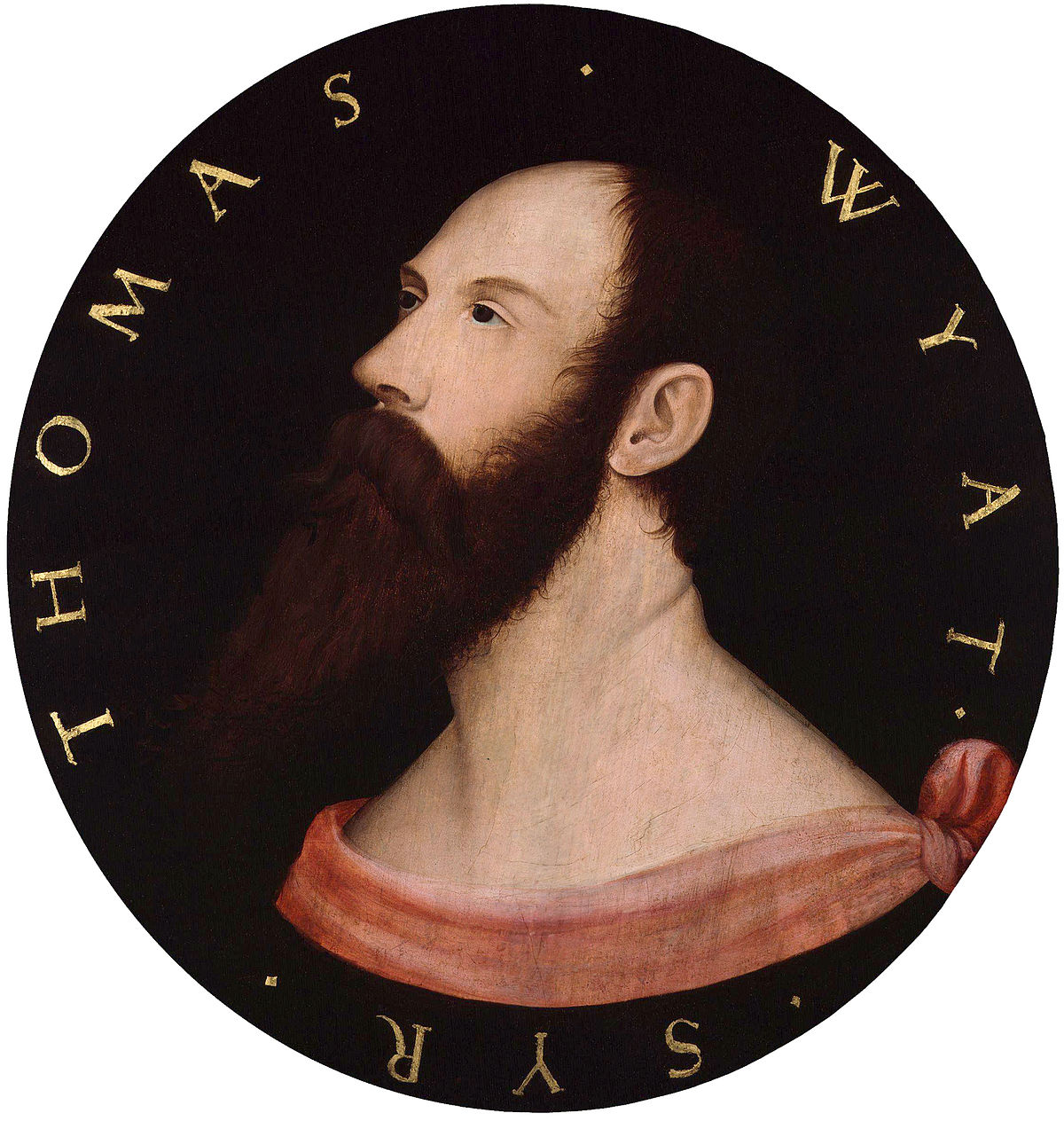

Whether the visit by Francis Yeardley was the start or the continuation of an ongoing courtship, he wooed Sarah Offley Thorowgood Gookin, and they were married within six months . They then lived on Sarah’s estate in Lower Norfolk County. That next year Yeardley patented additional adjoining lands based on transporting more headrights: 20 English, 7 Africans, and Simon, the Turk. [4]

This marriage likely surprised many. Francis was more than 10 years younger than Sarah.* There were obvious advantages for Francis, but what enticement was there for level-headed, wealthy Sarah? Sarah had enjoyed the legal advantages of being a “feme sole” for four years after the death of her second husband and had managed the estate well. Yet, she was also raising 5 children, and her daughters were coming near age for their own marriages. In addition, Sarah was locked in a dispute with the Lower Norfolk justices over the accounting of her children’s inheritances. Was she tiring of the business responsibilities or lonely for companionship or looking for a way to expand and enhance her social experiences and the status of her children? Their marriage seemed to be one of mutual convenience, but there must also have been some spark that drew these two dynamic personalities together, as there were likely other viable suitors. Smart Sarah, though, had learned from the example of Francis’ mother, Lady Temperance Yeardley, and set up a pre-nuptial arrangement to protect her finances before her third marriage. [5] (See The Fascinating and Formidable Sarah Offley Thorowgood Gookin Yeardley of 17th Century Virginia)

The Custis Clan from Rotterdam

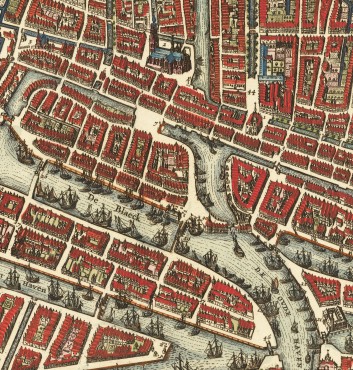

Argoll Yeardley’s life was also changing. Unfortunately, his wife Frances died around 1648, leaving him alone with their young children: Rose, Frances, and Argoll II. That following year, Argoll accompanied his tobacco shipment to Rotterdam and returned, perhaps unexpectedly, with their new stepmother, Ann Custis. It was an era of economic ties and competition between England and Holland, and numerous English merchants, such as Ann’s parents, Henry and Joan Custis, had moved to the cosmopolitan trade center of Rotterdam. In addition to their cloth business, Henry and Joan established St. John’s Head, a Rotterdam inn, that was popular with English merchants and ex-patriots. The Custises would have hosted many eligible and wealthy merchants, so we do not know what set Argoll apart that Ann should agree to leave her comfortable home for the challenges of the Eastern Shore. As with Sarah Offley’s marriage to Adam Thorowgood, Ann must have had a courageous and adventuresome spirit. [6]

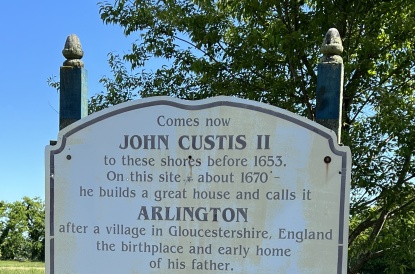

Ann’s acceptance of the marriage proposal brought the Custis family to Virginia. Her uncle, John Custis I, may have accompanied them or arrived shortly thereafter. Although John I conducted business, acquired property, and made periodic visits, he never settled there. However, Ann and Argoll Yeardley enticed her brothers John Custis II, William II, and Joseph, to join them, bringing a Custis dynasty to the New World. John II and William II who were born in Holland, though to English parents, were not naturalized by Act of Assembly until April 1658 which then allowed them to purchase land and hold office “as if they had been Englishmen born.” A woman’s citizenship was that of her husband. [7]

Ann’s acceptance of the marriage proposal brought the Custis family to Virginia. Her uncle, John Custis I, may have accompanied them or arrived shortly thereafter. Although John I conducted business, acquired property, and made periodic visits, he never settled there. However, Ann and Argoll Yeardley enticed her brothers John Custis II, William II, and Joseph, to join them, bringing a Custis dynasty to the New World. John II and William II who were born in Holland, though to English parents, were not naturalized by Act of Assembly until April 1658 which then allowed them to purchase land and hold office “as if they had been Englishmen born.” A woman’s citizenship was that of her husband. [7]

An Unexpected Guest

In 1650, Colonel Henry Norwood on his journey from England found himself stranded on the Eastern Shore. In his journal, he related that when he approached Argoll and Ann Yeardley, he was warmly received, having known Ann from when she was a child and her father who “kept a victualling house in that town, lived in good repute, and was the general host of our nation there.” Colonel Norwood said “I was received and caressed more like a domestic and near relation than a man in misery and a stranger. I stayed there for a passage over the bay, about ten days, welcomed and feasted not only by the esquire and his wife, but by many neighbors that were not too remote.” [8]

Sadly, the Yeardley’s house that provided such a welcome burned in 1651. However, we know from Argoll’s 1655 inventory that their next house was well furnished and had at least a hall chamber, a parlor chamber, a hall, two garrets, a kitchen, and a room over the kitchen as well as a dairy. Argoll and Ann Yeardley were living comfortably on the Eastern Shore and had the added joy of the birth of two sons, Edmund and Henry. Unfortunately, neither of them would have issue. [9]

Civil War Strife in Virginia

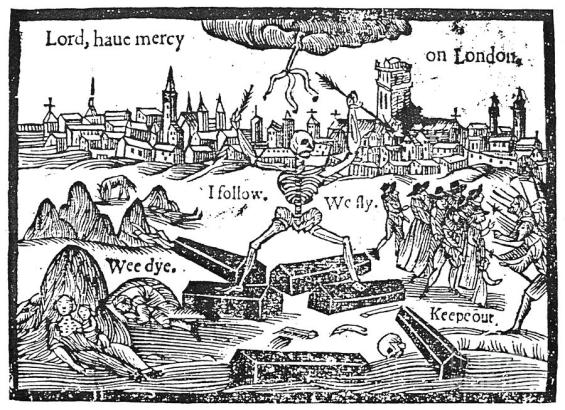

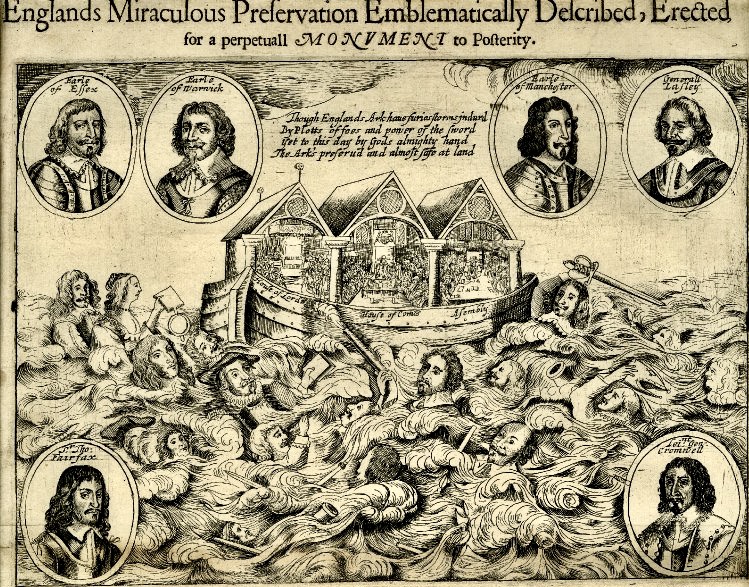

Meanwhile, England was being torn apart by Civil War. Gov. Berkeley, with whom Argoll served on the Council, maintained his loyalty to King Charles I and his son, Charles II, even after the king was beheaded in 1649. As noted in a prior post, Gov. Berkeley had actively persecuted the Virginia Puritans in Upper and Lower Norfolk, resulting in many moving to Maryland, and he had refused to comply with Parliament’s orders. On the Eastern Shore and elsewhere, several spoke out against the King which led the Assembly to prohibit speech in favor of the regicide, the change to Parliamentary governance, or in challenge to local government authority. At times, tensions flared. [10] (See Religious Tolerance/ Intolerance in 17th c Virginia)

Shortly after the English Civil War began, Richard Ingle, the master of the ship Reformation and an avowed supporter of the parliamentary cause, got into an argument with Francis Yeardley about the King and Parliament while he was docked on the Eastern Shore. Argoll, who was also on board, attempted to calm them. However, Ingle grabbed a poleax and a cutlass and ordered all Virginians off his ship. As a Councillor and the Commander of the Eastern Shore, Argoll responded, “I arrest you in the King’s name.” Ingle replied, “If you had arrested me in the King and Parliaments name I would have obeyed it for so it is now.” He then forced the Virginians, including Francis and Argoll, to leave his ship and sailed to Maryland, boasting of his defiance of Yeardley. However, months later, Argoll forgave Inge “of and from all manner of debts, suits, and controversies.”[11]

Shortly after the English Civil War began, Richard Ingle, the master of the ship Reformation and an avowed supporter of the parliamentary cause, got into an argument with Francis Yeardley about the King and Parliament while he was docked on the Eastern Shore. Argoll, who was also on board, attempted to calm them. However, Ingle grabbed a poleax and a cutlass and ordered all Virginians off his ship. As a Councillor and the Commander of the Eastern Shore, Argoll responded, “I arrest you in the King’s name.” Ingle replied, “If you had arrested me in the King and Parliaments name I would have obeyed it for so it is now.” He then forced the Virginians, including Francis and Argoll, to leave his ship and sailed to Maryland, boasting of his defiance of Yeardley. However, months later, Argoll forgave Inge “of and from all manner of debts, suits, and controversies.”[11]

Gov. Berkeley was finally forced to resign and surrender when ships with Parliamentary forces arrived in Virginia in 1652. Argoll Yeadley was appointed to the new Council of Richard Bennett, the Commonwealth’s Governor, and was tasked with obtaining the signatures of the Northampton residents who had to swear their allegiance to the Commonwealth. Whatever the citizens may have felt, this was done without incident.[12]

Sisters-in-Law: Ann & Sarah

Despite their age differences, Ann Custis and Sarah Offley Thorowgood Gookin had married the Yeardley brothers within two years of each other and became sisters-in-law. Their husbands continued to be involved in each other’s ventures and drew the Custis brothers into their affairs. But did Sarah and Ann ever meet or visit or write each other? The records are silent, but these two dynamic women surely knew of and influenced each other.

They likewise shared common grief in losing their Yeardley husbands a year apart: Argoll in 1655 and Francis in 1656. We do not know the circumstances of their deaths, but both died unexpectedly without wills. Did Sarah and Ann confide concerns about their husbands’ health or exchange condolences? Sarah died a year after Francis. They had not had any children together. [13]

They likewise shared common grief in losing their Yeardley husbands a year apart: Argoll in 1655 and Francis in 1656. We do not know the circumstances of their deaths, but both died unexpectedly without wills. Did Sarah and Ann confide concerns about their husbands’ health or exchange condolences? Sarah died a year after Francis. They had not had any children together. [13]

Argoll’s Insufficient Estate

Ann was appointed the executrix of Argoll’s estate when he died intestate. Settling his estate was complex. The inventory and appraisal of the estate on October 29, 1655 revealed that Argoll had 10 ewes, 16 cows, and 3 horses; 2 indentured servants with 3 months of service left in their contracts; and 2 Negro men, 2 Negro women (their wives), and 4 Negro children, only one of which was to be freed at adulthood (see prior post), providing further evidence that their Africans were enslaved, not indentured. The Yeardleys had lived comfortably with cupboards, beds, linens, a large Dutch looking glass (mirror), books, cookware, pewter, silver plate, a small boat, and more. Argoll’s estate was appraised at the equivalent of 41,269 pounds of tobacco which should have been adequate to pay off the usual debts.[14]

Ann was appointed the executrix of Argoll’s estate when he died intestate. Settling his estate was complex. The inventory and appraisal of the estate on October 29, 1655 revealed that Argoll had 10 ewes, 16 cows, and 3 horses; 2 indentured servants with 3 months of service left in their contracts; and 2 Negro men, 2 Negro women (their wives), and 4 Negro children, only one of which was to be freed at adulthood (see prior post), providing further evidence that their Africans were enslaved, not indentured. The Yeardleys had lived comfortably with cupboards, beds, linens, a large Dutch looking glass (mirror), books, cookware, pewter, silver plate, a small boat, and more. Argoll’s estate was appraised at the equivalent of 41,269 pounds of tobacco which should have been adequate to pay off the usual debts.[14]

However, growers of tobacco and trade merchants lived in a world of credit, and their cash flow was often in flux. At the moment of Argoll’s unexpected death, he had extended his credit beyond his means, for Ann reported to the court in November 1655 that she had paid out “a considerable sum of tobacco beyond assets to the creditors of her dead husband.” Ann Yeardley was ordered to find what she could to pay debts, but was granted a Quietus Est or termination of remaining debts by the court. Fortunately, real estate was not included in the assessment, so Argoll II still inherited his father’s property, and Ann received her widow’s dower interest which she released to Argol II when he agreed to deed land to her sons (his stepbrothers). [ 15]

However, growers of tobacco and trade merchants lived in a world of credit, and their cash flow was often in flux. At the moment of Argoll’s unexpected death, he had extended his credit beyond his means, for Ann reported to the court in November 1655 that she had paid out “a considerable sum of tobacco beyond assets to the creditors of her dead husband.” Ann Yeardley was ordered to find what she could to pay debts, but was granted a Quietus Est or termination of remaining debts by the court. Fortunately, real estate was not included in the assessment, so Argoll II still inherited his father’s property, and Ann received her widow’s dower interest which she released to Argol II when he agreed to deed land to her sons (his stepbrothers). [ 15]

Conspiracy? Follow the Money

How did a well respected gentleman such as Argoll end up in such a quandary? Some of his money might have been spent on the joint project initiated by his brother Francis to establish relations and trade with Roanoke tribes in North Carolina which Francis wrote about in 1654. The amount Argoll owed his notable Eastern Shore neighbors was only 11,604 pounds of tobacco which was able to be paid off. However, more than twice that (28,874 lbs. tobacco and 677 Dutch Guilders) was claimed by the Custis family. How could Argoll, who had hosted the emigrant Custises and provided them land, servants, and cattle, ended up owing them so much in just 5 years? John II, who could not yet purchase land, had even been leasing a plot from Argoll since 1653. [16]

On Christmas Day, 1654, Ann’s older brother, Edmund Custis III, was arrested in London with Henry Norwood and other co-conspirators in a plot to supply weapons for an anticipated revolt against Cromwell and for the restoration of the monarchy. The agents of John Thurloe, the Secretary of State and spymaster under Cromwell, discovered “5 chests and 2 trunks of arms now found at his (Edmund’s) house.”

According to one conspirator’s confession, the plan also included hiring a ship of one of Edmund’s brothers (likely Robert who was a shipmaster) to smuggle additional arms into England. Edmund claimed that the arms he had in the house were to send to Virginia, but the Commonwealth Assembly had not requested them. Edmund was sent to prison with Norwood. After Captain Norwood had innocently stayed at the Yeardley’s home in 1650, he had gone to Jamestown and may have initiated the plot in conjunction with Governor Berkeley. Assets of 1,000 pounds from Governor Berkeley were subsequently funneled to Edmund Custis.[17]

According to one conspirator’s confession, the plan also included hiring a ship of one of Edmund’s brothers (likely Robert who was a shipmaster) to smuggle additional arms into England. Edmund claimed that the arms he had in the house were to send to Virginia, but the Commonwealth Assembly had not requested them. Edmund was sent to prison with Norwood. After Captain Norwood had innocently stayed at the Yeardley’s home in 1650, he had gone to Jamestown and may have initiated the plot in conjunction with Governor Berkeley. Assets of 1,000 pounds from Governor Berkeley were subsequently funneled to Edmund Custis.[17]

The claims made against Argoll’s estate which included the 677 Guilders and 10,383 pounds of tobacco were due to this Edmund Custis, called innocently a London merchant, and his brother Joseph, who may have helped handle things while Edmund was imprisoned. John Custis, Sr. (Ann’s uncle) claimed he was owed 14,227 pounds, and John Custis II claimed 4,154 pounds based on goods delivered by his brother Robert to Argoll Yeardley in Virginia. For all the money owed to the Custises, there were no equivalent goods accounted for in the inventory or evidence of services rendered or shipments lost or in process. Perhaps the Custises had contributed when Argoll had to rebuild his burnt house several years before, but even that and the generally “old” furnishings in his household inventory would not equal what he owned.

The claims were made by the Custises who lived at least part-time in Virginia, avoiding review by an English court. Despite Argoll’s oath of allegiance to the Commonwealth, had some of his wealth gone to the purchasing of arms or the funding of a planned rebellion? Or had Argoll unsuccessfully invested in some of Edmund III’s shipping ventures, made even more risky during the First Anglo-Dutch War of 1652-1654? Knowing their sister/ niece’s situation, why did Ann’s family not forgive some of her debt? Edmund would later forgive John II a debt. Ann must have had a difficult and anxious year in 1655: her brother in prison, her husband dead, and her wealth gone. Ann’s brother, John Custis II, did assist her in settling the estate and handling the dwindled assets of her children. [18]

Married, Again

Ann Custis Yeardley soon remarried, as was common with Virginia widows. Not to be confused with the ancient planter John Wilcox who had also lived on the Eastern Shore, Ann’s second husband, John Wilcox/ Wilcocks served as a representative to the Assembly in 1658 and acted as an attorney for other settlers, served on a jury, and helped resolve disputes before the courts. Wilcocks owned land in the area known today as Pear Plain across from Argoll Yeardley on Hungars Creek. A child William was born to them in 1661, but unfortunately did not live long after his baptism. [19] (See The Widow Thorowgood and the Power and Perplexities of 17th Century Widows in Virginia)

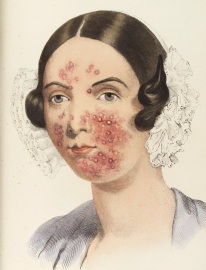

The Face Worth 1,000 Pounds

Jenean Hall uncovered from the Northampton Court records the story of John Wilcocks’ extraordinary concern for his wife. Ann Custis Yeardley Wilcocks developed unspecified sores on her face which led her husband to make an agreement with John Rhoads, a chirugeon (surgeon) then on the Eastern Shore, to pay 1,000 pounds of tobacco for his “paines and means” if Rhoads could provide a long term cure of her sores, lasting at least from spring through fall. Wilcocks later increased the offer to 2,000 pounds. This was a substantial offer. Rhoads expressed some hesitancy on his choice of treatments because Ann was pregnant at the time, but took the deal.

However, Wilcocks did not pay Rhoads that sum. Rhoads sued Wilcocks for payment in April 1662, but the Northampton court was not impressed by the treatment or improvement, for the justices found that the provision of his “diets” (meals–maybe room and board?) was “sufficient satisfaction for the medicines administered.” In addition, Rhoads had to pay the court costs. Unfortunately, in the following weeks, John Wilcocks became seriously ill and died, leaving Ann pregnant and widowed for the second time. Perhaps hoping to collect more from the estate of John Wilcocks, Rhoads again petitioned the court in October for payment for Ann’s treatment. The court, however, rejected it as it was the same plea and there was “no further cause of suit appearing, neither the cure manifested nor any other application used.” Once again, Rhoads had to pay court costs. [20]

Sadly, it seems Ann was not cured at the time, but many questions remain unanswered. Was this a case of exorbitant doctor fees or lofty claims of a cure that could not be provided? A gesture of love or a demand for vanity? What sort of sores were these? It was likely more than a case of usual acne or hormonal imbalance, as Ann had borne children before. Perhaps, acne had worsened with streptococcus or staphylococcus bacteria. The sores did not sound like pox marks which would not have had seasonal variation.

Sadly, it seems Ann was not cured at the time, but many questions remain unanswered. Was this a case of exorbitant doctor fees or lofty claims of a cure that could not be provided? A gesture of love or a demand for vanity? What sort of sores were these? It was likely more than a case of usual acne or hormonal imbalance, as Ann had borne children before. Perhaps, acne had worsened with streptococcus or staphylococcus bacteria. The sores did not sound like pox marks which would not have had seasonal variation.

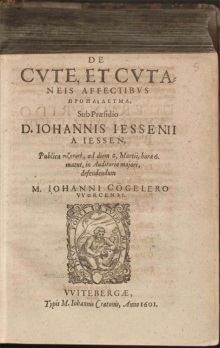

It had only been a few decades since the physician Jan Jessen had published his famous work On Skin and Skin Disorders, so there was still much uncertainty on the nature of human skin and the causes and treatment of skin problems. Lancing/ bleeding/leeches, face plasters, biologic treatments like honey or camphor oil, herbal applications like aloe or onion, more dangerous chemical applications of mercury, lead, or silver, or simply the control of one’s diet were all in practice. While understanding of diseases and treatments has changed over the centuries, the story of a loving husband’s support for his wife’s struggle for a cure still resonates today. [21]

Widowed, Again

In May 1662 just prior to his death, John Wilcocks prepared a will and shortly thereafter revised it. He left to his wife Ann his “whole estate real & personal lands and chattels during her natural life” which, on her decease, would go to their “child or children now in her womb.” But he was also inclusive of his stepsons, Henry and Edmond (Ann’s children with Argoll Yeardley), authorizing Ann to divide of his personal estate as inheritance for them as “to her shall seem fitting” and made them successively his heirs in case of the death of the child in the womb. He reminded his wife that he had “desired to be in some large measure helpful to the children or child of my brother Henry if he should have any.”

In May 1662 just prior to his death, John Wilcocks prepared a will and shortly thereafter revised it. He left to his wife Ann his “whole estate real & personal lands and chattels during her natural life” which, on her decease, would go to their “child or children now in her womb.” But he was also inclusive of his stepsons, Henry and Edmond (Ann’s children with Argoll Yeardley), authorizing Ann to divide of his personal estate as inheritance for them as “to her shall seem fitting” and made them successively his heirs in case of the death of the child in the womb. He reminded his wife that he had “desired to be in some large measure helpful to the children or child of my brother Henry if he should have any.”

In his codicil, he made it clear that “my beloved wife…shall solely and wholly enjoy my whole estate…giving no account of waste to any person.” He also specified that he forgave his brother any debts he owned him and designated that if there were a child of his brother, it would receive 200 acres and 6 cows. John Wilcocks was a generous man who clearly trusted his wife Ann, but unfortunately left no descendant to emulate him. There is circumstantial evidence, based mostly on land records, that Ann Custis Yeardley Wilcocks next married a younger man, John Luke, who lived with her on the Wilcocks property until her death. They had no children together. [22]

Legacies of the Ladies

The Thorowgoods are rarely acknowledged in Eastern Shore history; yet as Francis’ wife, the powerful Sarah would have had some impact on affairs there. The Thorowgood genes and heritage infused the Eastern Shore through the marriage of her daughter Elizabeth Thorowgood to John Michaels, and thus to their Custis grandchildren. The Yeardley genes and heritage likewise came to Lower Norfolk through Argoll’s daughter Frances Yeardley II who married Adam Thorowgood II. The Thorowgood, Custis, and Yeardley women may not be the names that are usually remembered in history, but they played important roles in weaving the complex tapestry of the developing Virginia society.

The Thorowgoods are rarely acknowledged in Eastern Shore history; yet as Francis’ wife, the powerful Sarah would have had some impact on affairs there. The Thorowgood genes and heritage infused the Eastern Shore through the marriage of her daughter Elizabeth Thorowgood to John Michaels, and thus to their Custis grandchildren. The Yeardley genes and heritage likewise came to Lower Norfolk through Argoll’s daughter Frances Yeardley II who married Adam Thorowgood II. The Thorowgood, Custis, and Yeardley women may not be the names that are usually remembered in history, but they played important roles in weaving the complex tapestry of the developing Virginia society.

* There is question regarding the birth years of Argoll and Francis Yeardley. The 1624 Muster recorded Argoll as 4; Frances as 1; and their older sister as 6 years old while living in James City with their parents. A birth year of 1619/20 for Argoll meant he would have been unusually young when he married, inherited his father’s lands, and was placed on the Council. Likewise, Frances would have been young to receive a patent for bringing headrights. Disparities in the ages listed for other individuals in the Muster have raised questions as to what reference point was used, i.e. Adam Thorowgood was listed as 18, although he was 20 in 1624. In depositions given in 1630 for the suit Yardley v. Rossingham (C24/561 Pt2/136), William Claiborne stated “the eldest son known by Argall Yardley… being of the age of some thirteen years or thereabouts and the second of the age of some twelve years.” Susanna Hall stated in her deposition that the daughter was “some 16 years of age or thereabouts; the eldest son some 14 years old, and the youngest some 12 years old.” This would adjust Argoll’s birthdate to about 1616 or 1617 and Francis’ birthdate to around 1618 or 1619. The adjusted dates seem more reasonable. [See footnote 5]

Next Post: Dutch Merchants in the Chesapeake and Thorowgood Brides

Special Thanks to Jenean Hall, Eastern Shore historian and author, and Jorja Jean, Virginia Beach historian and researcher, for their insights and assistance.

Footnotes:

- Walter, Alice Granberry, Lower Norfolk County Virginia, Court Records: Book “B” 1646-1651/2 (Baltimore: Clearfield, 2009), 40-41. Turner, Florence Kimberly, Gateway to the New World: A History of Princess Anne County Virginia, 1607-1824 (Easley, South Carolina: Southern Historical Press, 1984), 55.

- Walter, Book “B,” 59-60. Pieczynski, Christopher, The Pleasure House: A Research Study Submitted to the Virginia Beach Historic Preservation Commission (June 30, 2020). Accessed 4/20/2023 online at https://www.vb.gov.com

- Luccketti, Nicholas M., Robert Haas and Mathew Laird, Archaeological Assessment of the Chesopean Site, Virginia Beach, Virginia (Williamsburg, VA: James River Institute for Archaeology, Inc, December 2006), 6-7, 28-30. Outlaw, Merry and Bly Bogley (cataloguers), “Site Number 44VB48: Thorowgood or Chesopean, Virginia Beach,” Archaeological Specimen Catalog for The Virginia Research Center for Archaeology, 1980.

- Walter, Book “B,” 53 (53a), 49 ( 50), 58-59 (60), 74 (76a), 81 ( 90a).

- Morgan, Edmund S., American Slavery, American Freedom (New York: W.W. Norton, 1975), 166-167. Hotten, John Camden, The Original Lists of Persons of Quality (Berryville, Virginia: Virginia Book Company, 1980; originally published in London, 1874), 123, 222. Dorman, John Frederick, Adventurers of Purse and Person Virginia 1607-1624/5, v. 3, 4th edition (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co, Inc., 2007), 865-866. McCarthy, Martha W., Virginia Immigrants and Adventurers, 1607-1635 (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 2007), 775. Nugent, Nell Marion, Cavaliers and Pioneers: Abstracts of Virginia Land Patents and Grants 1623-1666, v. 1 (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1979), 81. Currer-Briggs, Noel, “Parentage and Ancestry of Sir George Yeardley and Temperance Flowerdew,” National Genealogical Society Quarterly, 66, 17-28.

- Dorman, 866. Whitelaw, Ralph T., Virginia’s Eastern Shore, v.1 (Richmond: Virginia Historical Society, 1950), 289. Lynch, James B., Jr, The Custis Chronicles: The Years of Migration (Camden, Maine: Picton Press, 1992), 36-37, 49-50.

- Lynch, 137-151, 159-160, 217. McCartney, Jamestown People to 1800 (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company, 2012), 131-134.

- Lynch 137-138. Whitelaw, 289. Turman, Nora Miller, The Eastern Shore of Virginia 1603-1964, (Onancock, Virginia: The Eastern Shore News, Inc., 1964), 49-51.

- Whitelaw, 289. Dorman 866. Bruce, Philip Alexander, Economic History of Virginia in the Seventeenth Century (New York: The MacMillan Company, 1907), 157. Mackey, Howard and Marlene A. Groves, Northampton County Virginia Record Book: Orders, Deed, Wills 1654-1655, v. 5 (Rockport, Maine, Picton Press, 1999), 222-225.

- Perry, James R., The Formation of a Society on Virginia’s Eastern Shore, 1615-1655 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1990), 209-210. Wise, Jennings Cropper, Ye Kingdome of Accawmacke or the Eastern Shore of Virginia in the Seventeenth Century (Richmond: The Bell Book and Stationary Co., 1911), 133-136.

- Perry 207. Hall, Jenean, unpublished papers, 2023.

- Bond, Edward L., Damned Souls in a Tobacco Colony: Religion in Seventeenth Century Virginia (Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2000), 158-159. Neill, Edward D. Virginia Carolorum: The Colony Under the Rule of Charles the First and Second (Albany:Joel Munsell’s and Sons, 1886, reprinted by Scholar Select), 217-225.

- Dorman, 328, 865-866.

- Turner, Nora MIller and Mark C. Lewis, “Inventory of the Estate of Argoll Yeardley of Northampton County, Virginia in 1655,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, 70:4 (October 1962), 410-419. Whitelaw, 290.

- Mackey, Howard and Marllene A. Groves, Northampton County Virginia Record Book: Deeds, Wills & Etc. 1665-1657, v. 6 and 7-8 (Rockport, Maine: Picton Press, 2002), 37-38.

- Mackey, v.6 and 7-8, p. 9-10, 21-22. Lynch, 160. Salley, Alexander S., Jr., (editor), Narratives of Early Carolina 1650-1708 (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1911. Facsimile copy by Elibron Classics, 2005), 25-29. “Money in the 17th century Netherlands,” accessed online 7/3/23 at Dutch money

- Lynch, 63-66, 106-107. Harrison, Fairfax, “Henry Norwood (1615-1689),” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, 33:1 (January 1925), 6-7. “Henry Norwood,” wikipedia. Accessed online 7/3/23.

- Mackey, v.6 and 7-8, p. 9-10. Lynch, 58-59.

- McCartney, Jamestown, 446. Whitelaw, 412-413. Mackey, Howard and Candy McMahan Perry, NorthamptonCounty Virginia Record Book: Deeds, Wills & Etc 1637-1666, v. 7, (Rockport, Maine: Picton Press, 2002), 175-176. Lynch, 139. Hall, Jenean, unpublished papers, 2023.

- Mackey, Howard and Marlene A. Groves, Northampton Count Virginia Record Book: Court Cases 1637-1664, v.8 (Rockport, Maine: Picton Press, 2002), 228-229, 269-270. Hall, Jenean, unpuplished papers, 2023.

- Murphy H., Skin and Disease in Early Modern Medicine: Jan Jessen’s De cute, et cutaneis affectibus (1601). Bull Hist Med. 2020;94(2):179-214. doi: 10.1353/bhm.2020.0034. PMID: 33416551; PMCID: PMC7850318. Mahmood NF, Shipman AR. The age-old problem of acne. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2016 Dec 2;3(2):71-76. doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2016.11.002. PMID: 28560299; PMCID: PMC5440448.

- Lynch, 138-139, 224-225. Whitelaw, 412-413. Hall, Jenean, unpublished papers, 2023.

Sadly, very little was created and even less preserved to document the thoughts and lives of these women, so we must again turn to the stories and documents of the men to catch them in the shadows. In the prior post, the children of Gov. George and Lady Temperance Yeardley were left orphaned in Jamestown and returned to England under the guardianship of their uncle, Ralph Yeardley. Nothing is known of their English childhoods. Their uncle was an apothecary of the merchant class, but with the wealth and status of Sir & Lady Yeardley, these orphans likely had an advantageous upbringing and an acquaintance with the cultured ways of English society. The daughter Elizabeth then disappeared from the records, hopefully through marriage rather than death. Argoll and Francis reappeared when they returned to Virginia to claim their inheritances. (See

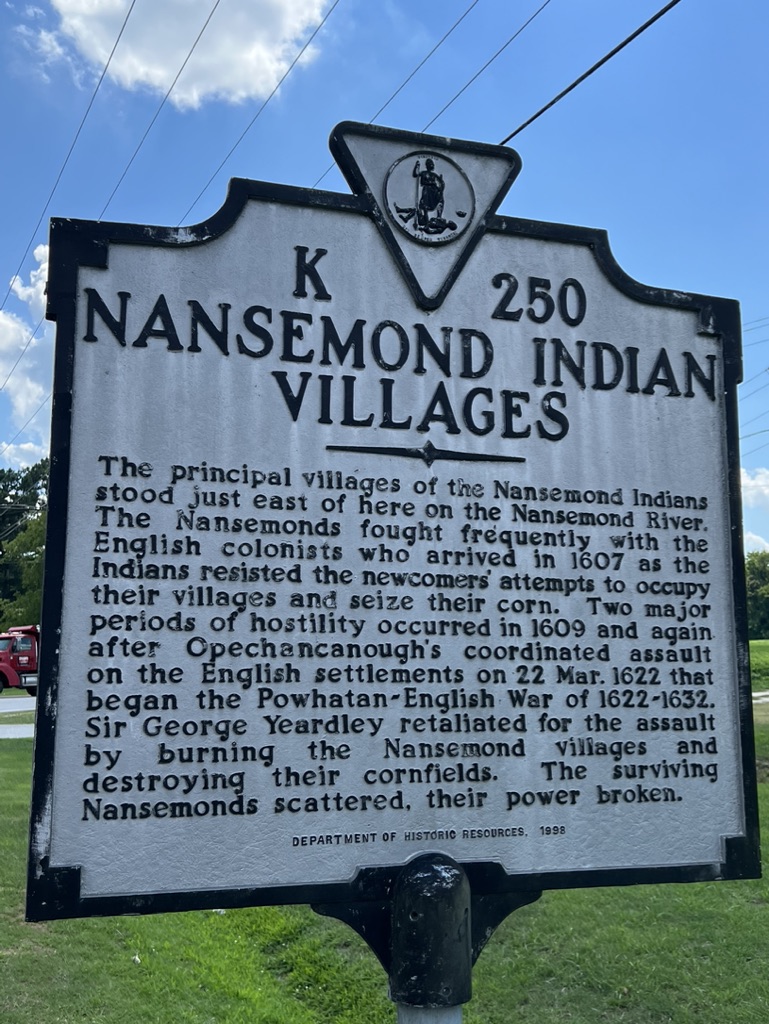

Sadly, very little was created and even less preserved to document the thoughts and lives of these women, so we must again turn to the stories and documents of the men to catch them in the shadows. In the prior post, the children of Gov. George and Lady Temperance Yeardley were left orphaned in Jamestown and returned to England under the guardianship of their uncle, Ralph Yeardley. Nothing is known of their English childhoods. Their uncle was an apothecary of the merchant class, but with the wealth and status of Sir & Lady Yeardley, these orphans likely had an advantageous upbringing and an acquaintance with the cultured ways of English society. The daughter Elizabeth then disappeared from the records, hopefully through marriage rather than death. Argoll and Francis reappeared when they returned to Virginia to claim their inheritances. (See  Sir George had left his sons the acreage he had received on the Eastern Shore (Chesapeake Penninsula) from the Accomac chieftain called The Laughing King. However, that was not where Argoll acquired his first property in Virginia. Before returning to Virginia, Argoll had married Frances Knight of London and so listed her as one of his headrights to patent 500 acres of land on Dumpling Island on the Nansemond River in Upper Norfolk County (later Nansemond Co.) in February 1637/38. An approximate birthdate of 1620 based on the 1624 Jamestown census would have made Argoll only about 18 years old when he patented land, which was unusually young for that time. There is some question as to the reference point of the ages on the Muster, and depositions given in 1630, indicate that Argoll and Francis were about two years older than reported on the Muster.* To maintain a land claim, it had to be “seated” (settled) and there had to be improvements made on the land. It is unknown what kind of improvements Argoll made there or whether he or Francis ever lived in Upper Norfolk . [2]

Sir George had left his sons the acreage he had received on the Eastern Shore (Chesapeake Penninsula) from the Accomac chieftain called The Laughing King. However, that was not where Argoll acquired his first property in Virginia. Before returning to Virginia, Argoll had married Frances Knight of London and so listed her as one of his headrights to patent 500 acres of land on Dumpling Island on the Nansemond River in Upper Norfolk County (later Nansemond Co.) in February 1637/38. An approximate birthdate of 1620 based on the 1624 Jamestown census would have made Argoll only about 18 years old when he patented land, which was unusually young for that time. There is some question as to the reference point of the ages on the Muster, and depositions given in 1630, indicate that Argoll and Francis were about two years older than reported on the Muster.* To maintain a land claim, it had to be “seated” (settled) and there had to be improvements made on the land. It is unknown what kind of improvements Argoll made there or whether he or Francis ever lived in Upper Norfolk . [2] A few months later in September 1638, Argoll Yeardley, was designated as Esquire (a gentleman, not a lawyer) and was granted 3700 acres as his father’s inheritance on Hungars Creek in Accomack Co. (later Northampton Co.) of the Eastern Shore. Despite his young age, he was quickly accepted into the developing elite Virginia society and was recommended by Sir Francis Wyatt for his Governor’s Council. While Burgesses were elected, councillors were recommended by the governor and appointed for life by the King, with vacancies often filled by the sons or relatives of former councillors. Argoll would have served briefly with Adam Thorowgood on the Council before Adam suddenly died in 1640. [3]

A few months later in September 1638, Argoll Yeardley, was designated as Esquire (a gentleman, not a lawyer) and was granted 3700 acres as his father’s inheritance on Hungars Creek in Accomack Co. (later Northampton Co.) of the Eastern Shore. Despite his young age, he was quickly accepted into the developing elite Virginia society and was recommended by Sir Francis Wyatt for his Governor’s Council. While Burgesses were elected, councillors were recommended by the governor and appointed for life by the King, with vacancies often filled by the sons or relatives of former councillors. Argoll would have served briefly with Adam Thorowgood on the Council before Adam suddenly died in 1640. [3] In January 1641/42, Argoll was also appointed a commissioner and justice for Accomack County. However, not all residents were content with this young man’s authority. A contentious resident Thomas Parks was sent for trial by the Council (of which Argoll was a part) in 1643 for insulting and slandering Argoll’s parents’ background, disputing Argoll’s fairness, and threatening to take his grievances to Maryland or the native tribes (which could have stirred up trouble). Parke did not seem to learn that disrespect toward those in authority would not be tolerated, as he reappeared in court a few months later for affronting Yeardley and other commissioners and received 30 lashes. Two years later, he defamed Commissioner Obedience Robins, but was spared another whipping when he finally apologized. However, the councillors themselves were not above reprimands. Argoll himself was charged with contempt in 1644. [4]

In January 1641/42, Argoll was also appointed a commissioner and justice for Accomack County. However, not all residents were content with this young man’s authority. A contentious resident Thomas Parks was sent for trial by the Council (of which Argoll was a part) in 1643 for insulting and slandering Argoll’s parents’ background, disputing Argoll’s fairness, and threatening to take his grievances to Maryland or the native tribes (which could have stirred up trouble). Parke did not seem to learn that disrespect toward those in authority would not be tolerated, as he reappeared in court a few months later for affronting Yeardley and other commissioners and received 30 lashes. Two years later, he defamed Commissioner Obedience Robins, but was spared another whipping when he finally apologized. However, the councillors themselves were not above reprimands. Argoll himself was charged with contempt in 1644. [4]

The Eastern Shore settlement grew outwards along the bayside from the inlet at Old Plantation and the Ackomack River (later called Cherrystone) to King’s Creek and further up to Hungars and Nassawadox where the Yeardleys lived. As the land was divided by many streams and inlets, travel would have been challenging, going either by skiff (small open boat) or by walking paths around the water and marshy lands. It is likely that most of Frances’ social network would have been within a five mile radius (journey of an hour or two), as was found in a study of 17th c women in the Chesapeake area. Church and court days would have increased opportunities to develop relationships. [5]

The Eastern Shore settlement grew outwards along the bayside from the inlet at Old Plantation and the Ackomack River (later called Cherrystone) to King’s Creek and further up to Hungars and Nassawadox where the Yeardleys lived. As the land was divided by many streams and inlets, travel would have been challenging, going either by skiff (small open boat) or by walking paths around the water and marshy lands. It is likely that most of Frances’ social network would have been within a five mile radius (journey of an hour or two), as was found in a study of 17th c women in the Chesapeake area. Church and court days would have increased opportunities to develop relationships. [5] Frances must have been delighted when Argoll got a horse in 1642 (the first known horse purchased on the Eastern Shore) and continued to expand his herd. Hopefully, Frances had use of the horses, although it might have created some local jealousy as happened when Sarah Thorowgood rode her horse in Lower Norfolk. Overall, horses continued to be scarce on the Eastern Shore with only 6 landowners having horses by 1650 which only grew to 22 by 1655.

Frances must have been delighted when Argoll got a horse in 1642 (the first known horse purchased on the Eastern Shore) and continued to expand his herd. Hopefully, Frances had use of the horses, although it might have created some local jealousy as happened when Sarah Thorowgood rode her horse in Lower Norfolk. Overall, horses continued to be scarce on the Eastern Shore with only 6 landowners having horses by 1650 which only grew to 22 by 1655.

Despite Francis’ young age and lack of any military experience, Gov. Berkeley appointed him as a captain of the militia shortly after his arrival in Virginia. Francis had the authority “to appoint subordinate officers, exercise his company once a month, and levy a special tax to raise funds for the purchase of a drum, colors, and tent” for the King’s Creek to Hungars Creek area. Although relations were generally peaceful with the Accomac tribe on the Eastern Shore when Francis was appointed, the militia was reorganized shortly thereafter in response to increasing colony concerns in the era of the third Anglo-Powhatan War from 1644-1646. Francis continued as a captain, but Argoll eventually became the Commander of the Eastern Shore. [12]

Despite Francis’ young age and lack of any military experience, Gov. Berkeley appointed him as a captain of the militia shortly after his arrival in Virginia. Francis had the authority “to appoint subordinate officers, exercise his company once a month, and levy a special tax to raise funds for the purchase of a drum, colors, and tent” for the King’s Creek to Hungars Creek area. Although relations were generally peaceful with the Accomac tribe on the Eastern Shore when Francis was appointed, the militia was reorganized shortly thereafter in response to increasing colony concerns in the era of the third Anglo-Powhatan War from 1644-1646. Francis continued as a captain, but Argoll eventually became the Commander of the Eastern Shore. [12] Francis did not appear to have his older brother’s business skills. In a tobacco economy based upon the annual sale of the crop, it could be tricky to manage finances. While Francis was land rich, his bills were not always paid on time. In 1646, the county court on which his brother sat found Francis owed Thomas Savage, a cooper/carpenter, for his 4 years of service (possibly from an indentureship) 2 suits of clothes, 2 pair shoes, Irish stockings, 2 shirts, 1 cap, and 1 servants bed. Mr. Stephen Charlton had earlier warned a prospective worker to avoid working for Mr. Yeardley who, though a gentleman, had not given Thomas Savage anything for his work for 2 years. Francis Yeardley was also ordered in 1646 to pay his debts of £6+ to Obedience Robins and 50 guilders to William Waters. The bachelor Francis, though, was resourceful and improved his situation that next year by moving and marrying a rich Virginia widow. [13]

Francis did not appear to have his older brother’s business skills. In a tobacco economy based upon the annual sale of the crop, it could be tricky to manage finances. While Francis was land rich, his bills were not always paid on time. In 1646, the county court on which his brother sat found Francis owed Thomas Savage, a cooper/carpenter, for his 4 years of service (possibly from an indentureship) 2 suits of clothes, 2 pair shoes, Irish stockings, 2 shirts, 1 cap, and 1 servants bed. Mr. Stephen Charlton had earlier warned a prospective worker to avoid working for Mr. Yeardley who, though a gentleman, had not given Thomas Savage anything for his work for 2 years. Francis Yeardley was also ordered in 1646 to pay his debts of £6+ to Obedience Robins and 50 guilders to William Waters. The bachelor Francis, though, was resourceful and improved his situation that next year by moving and marrying a rich Virginia widow. [13] So, how did Ann Custis from Rotterdam and Sarah Offley Thorowgood Gookin from Lower Norfolk County, Virginia, get entangled in this story and end up as sisters in law? What impact did they have on the Eastern Shore story? Did Sarah really run a tavern? And whose complexion was worth 1,000 lbs. of tobacco?

So, how did Ann Custis from Rotterdam and Sarah Offley Thorowgood Gookin from Lower Norfolk County, Virginia, get entangled in this story and end up as sisters in law? What impact did they have on the Eastern Shore story? Did Sarah really run a tavern? And whose complexion was worth 1,000 lbs. of tobacco? If Sarah Offley Thorowgood Gookin Yeardley had had a chance to meet her new mother-in law when she married Francis Yeardley as her third husband, they likely would have found much in common. However, Temperance Flowerdew Barrow Yeardley West died in Jamestown in 1628, leaving her three young children, Elizabeth, Argoll, and Francis, orphaned. The children’s father, Sir George Yeardley, Governor of Virginia, had died in 1627. Not only did Sarah and Temperance each marry three times and survive challenging times in the Colony, they were both smart and powerful women who managed large estates, married wisely, and ensured the future prosperity of their children. [1] (See:

If Sarah Offley Thorowgood Gookin Yeardley had had a chance to meet her new mother-in law when she married Francis Yeardley as her third husband, they likely would have found much in common. However, Temperance Flowerdew Barrow Yeardley West died in Jamestown in 1628, leaving her three young children, Elizabeth, Argoll, and Francis, orphaned. The children’s father, Sir George Yeardley, Governor of Virginia, had died in 1627. Not only did Sarah and Temperance each marry three times and survive challenging times in the Colony, they were both smart and powerful women who managed large estates, married wisely, and ensured the future prosperity of their children. [1] (See:

Along with his political advancement, George Yeardley went from arriving in 1610 with “nothing more valuable than a sword ” to becoming the wealthiest man in the colony. Yeardley was shrewd and figured out how to turn things to his favor and make a profit, particularly in the acquisition and sale of real estate. Rather than receiving a salary, governors under the Virginia Company were granted 3,000 acres outside Jamestown known as the “Governor’s Lands” to manage and profit from and then to pass on to the next governor. However, arrangements were not always adequately spelled out. When Yeardley’s first term as governor ended, he contested that he had agreed to transfer all the Company workers that had been sent to him to the newly appointed Gov. Wyatt. [8]

Along with his political advancement, George Yeardley went from arriving in 1610 with “nothing more valuable than a sword ” to becoming the wealthiest man in the colony. Yeardley was shrewd and figured out how to turn things to his favor and make a profit, particularly in the acquisition and sale of real estate. Rather than receiving a salary, governors under the Virginia Company were granted 3,000 acres outside Jamestown known as the “Governor’s Lands” to manage and profit from and then to pass on to the next governor. However, arrangements were not always adequately spelled out. When Yeardley’s first term as governor ended, he contested that he had agreed to transfer all the Company workers that had been sent to him to the newly appointed Gov. Wyatt. [8]

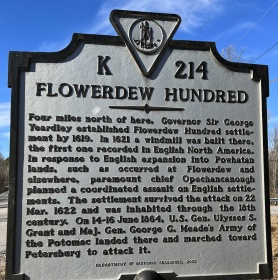

Yeardley was also among those to establish a “particular plantation” or “hundred” where more profit could be made than when working lands under Company control. He purchased 1,000 acres along the James River in 1619 and named it Flowerdew Hundred after his wife’s family name. Stanley Flowerdew, Temperance’s brother who had also come to Virginia, took a shipment of tobacco to England that year, so some portion of the plantation may have already been under cultivation. Yeardley built the first windmill known in the colonies, but continued to reside in Jamestown with his family. In 1624, he decided to sell Flowerdew to Abraham Piersey who renamed it Piersey’s Hundred. [11]

Yeardley was also among those to establish a “particular plantation” or “hundred” where more profit could be made than when working lands under Company control. He purchased 1,000 acres along the James River in 1619 and named it Flowerdew Hundred after his wife’s family name. Stanley Flowerdew, Temperance’s brother who had also come to Virginia, took a shipment of tobacco to England that year, so some portion of the plantation may have already been under cultivation. Yeardley built the first windmill known in the colonies, but continued to reside in Jamestown with his family. In 1624, he decided to sell Flowerdew to Abraham Piersey who renamed it Piersey’s Hundred. [11]

In 1617, Powhatan Chief Opechancanough gave Yeardley 2,200 acres of the lands of the Weyanock tribe almost directly across the James River from Flowerdew. The reason for the gift is unknown. Was he trying to curry favor with Yeardley or responding to pressure? Was it punishment for the Weyanocks, an attempt to maintain their presence in the midst of the English, or part of a larger plan to destroy the English? Even though the land was occupied by the tribe, the Virginia Company felt it needed to ratify the deal which it approved “in consideration of the long good and faithful service done by you, Captain George Yeardley,…in the Colony.”

In 1617, Powhatan Chief Opechancanough gave Yeardley 2,200 acres of the lands of the Weyanock tribe almost directly across the James River from Flowerdew. The reason for the gift is unknown. Was he trying to curry favor with Yeardley or responding to pressure? Was it punishment for the Weyanocks, an attempt to maintain their presence in the midst of the English, or part of a larger plan to destroy the English? Even though the land was occupied by the tribe, the Virginia Company felt it needed to ratify the deal which it approved “in consideration of the long good and faithful service done by you, Captain George Yeardley,…in the Colony.” The Weyanocks continued to live peaceably among Yeardley’s indentured servants for several years. However, when they rose up on March 22 as part of the Powhatan Offensive, they slaughtered all 22 of the English living there. Yeardley personally sought revenge on the Weyanocks, but when he arrived, the tribe had left, and the settlement was devoid of humans. In 1624, he sold the land to Piersey along with Flowerdew. [13]

The Weyanocks continued to live peaceably among Yeardley’s indentured servants for several years. However, when they rose up on March 22 as part of the Powhatan Offensive, they slaughtered all 22 of the English living there. Yeardley personally sought revenge on the Weyanocks, but when he arrived, the tribe had left, and the settlement was devoid of humans. In 1624, he sold the land to Piersey along with Flowerdew. [13]

Creating Yeardley’s wealth on these plantations was his labor force of English indentured servants and Africans. The first Africans arrived in 1619 aboard The White Lion at Point Comfort (Hampton), Virginia, having been captured by English privateers from a slave ship in the Gulf of Mexico. Governor Yeardley and Abraham Piersey, the Company’s cape merchant, agreed to give the crew needed provisions in exchange for the “twenty and odd Negroes.”

Creating Yeardley’s wealth on these plantations was his labor force of English indentured servants and Africans. The first Africans arrived in 1619 aboard The White Lion at Point Comfort (Hampton), Virginia, having been captured by English privateers from a slave ship in the Gulf of Mexico. Governor Yeardley and Abraham Piersey, the Company’s cape merchant, agreed to give the crew needed provisions in exchange for the “twenty and odd Negroes.”

Then the unthinkable, but sadly not the unusual, happened. Within eight months of Temperance’s remarriage and slightly over a year after Sir George’s death, she died in December 1628. It must have been sudden for, with all her careful record keeping, she died without a will. What was to happen to the children? And all the wealth?

Then the unthinkable, but sadly not the unusual, happened. Within eight months of Temperance’s remarriage and slightly over a year after Sir George’s death, she died in December 1628. It must have been sudden for, with all her careful record keeping, she died without a will. What was to happen to the children? And all the wealth? On February 14, 1628/9, Ralph Yeardley, an apothecary in London and brother of George Yeardley, was given the commission ” to administer the goods and chattels of the said deceased during the minority of Elizabeth Yeardley, Argoll Yeardley, and Francis Yeardley.” It is presumed that the children returned to England under the care of their uncle, although nothing is known of their childhoods there. Elizabeth disappeared from the records at that point, whether through an early death or a change of name through marriage is unknown. Argoll and Francis’ documented stories do not resume until they returned to Virginia to claim their inheritances. [19]

On February 14, 1628/9, Ralph Yeardley, an apothecary in London and brother of George Yeardley, was given the commission ” to administer the goods and chattels of the said deceased during the minority of Elizabeth Yeardley, Argoll Yeardley, and Francis Yeardley.” It is presumed that the children returned to England under the care of their uncle, although nothing is known of their childhoods there. Elizabeth disappeared from the records at that point, whether through an early death or a change of name through marriage is unknown. Argoll and Francis’ documented stories do not resume until they returned to Virginia to claim their inheritances. [19]

Inspired by Cromwell’s successes, Parliament was preparing at the end of 1644 to reorganize its army into the national New Model Army which would emphasize efficiency and merit. In an attempt to make this new army less political, those serving in both the military and Parliament were forced to choose between those positions through the Self-Denying Ordinance. However, the army ended up with greater representation of Independents like Cromwell than fervent Presbyterians which ultimately resulted in its own conflicts. While the New Model Army’s focus was to win battles, there was a general religious orientation, and they were issued a special Soldiers Catechism. It was also the first time there was a national uniform created for the troops who became called “redcoats.” [5]

Inspired by Cromwell’s successes, Parliament was preparing at the end of 1644 to reorganize its army into the national New Model Army which would emphasize efficiency and merit. In an attempt to make this new army less political, those serving in both the military and Parliament were forced to choose between those positions through the Self-Denying Ordinance. However, the army ended up with greater representation of Independents like Cromwell than fervent Presbyterians which ultimately resulted in its own conflicts. While the New Model Army’s focus was to win battles, there was a general religious orientation, and they were issued a special Soldiers Catechism. It was also the first time there was a national uniform created for the troops who became called “redcoats.” [5]

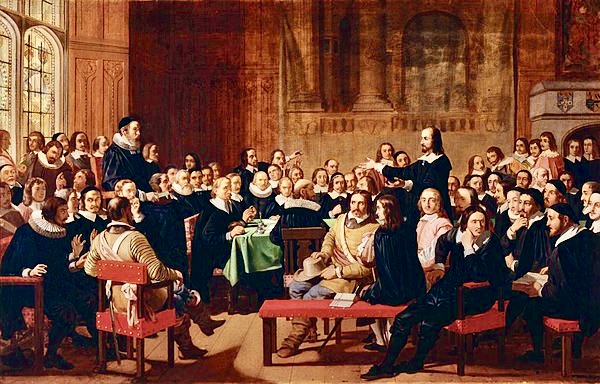

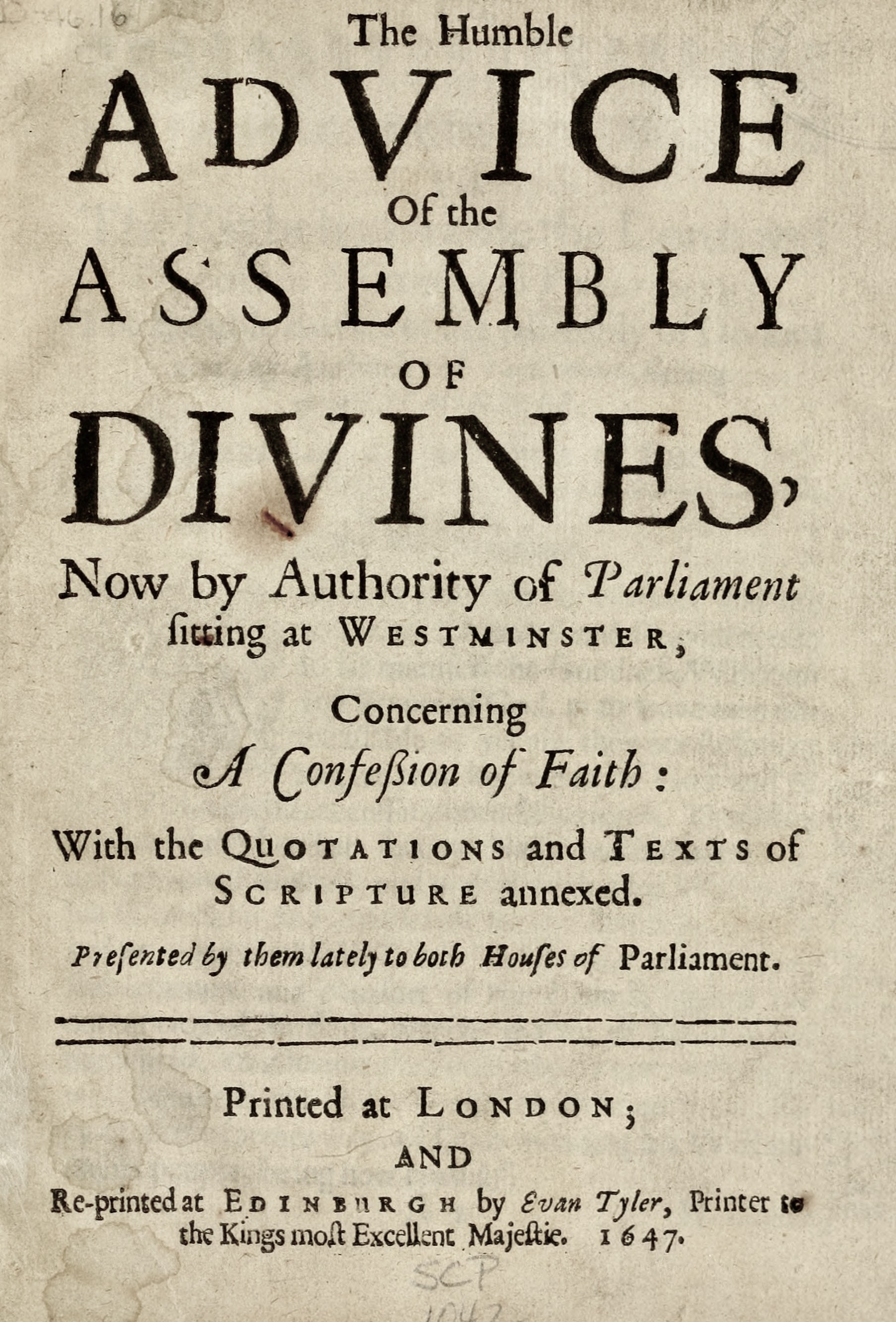

In April 1642, Parliament authorized the calling of an Anglo-Scottish synod of “divines” to revise the prayer book (rejecting the Anglican Common Book of Prayer) and decide matters regarding acceptable church liturgy, practices, and governance. Invited were 121 ordained ministers, 10 peers, 20 MPs as lay assessors, and 8 Scots (5 clerics and 3 laymen). The Assembly opened on July 1, 1643 at Westminster and continued until 1653. No Anglican ministers were appointed. Thomas Thorowgood was one of two selected to represent Norfolk, and he served from 1643 until 1649. In 1646, the Assembly published a New Confession of Faith based on Calvinistic doctrine and prescribed a Presbyterian form of church governance. Although the church in Scotland continued to employ the Westminster Assembly’s standards, they were revoked in England in 1660 when the Anglican Church was reinstated with the restoration of Charles II. [8]

In April 1642, Parliament authorized the calling of an Anglo-Scottish synod of “divines” to revise the prayer book (rejecting the Anglican Common Book of Prayer) and decide matters regarding acceptable church liturgy, practices, and governance. Invited were 121 ordained ministers, 10 peers, 20 MPs as lay assessors, and 8 Scots (5 clerics and 3 laymen). The Assembly opened on July 1, 1643 at Westminster and continued until 1653. No Anglican ministers were appointed. Thomas Thorowgood was one of two selected to represent Norfolk, and he served from 1643 until 1649. In 1646, the Assembly published a New Confession of Faith based on Calvinistic doctrine and prescribed a Presbyterian form of church governance. Although the church in Scotland continued to employ the Westminster Assembly’s standards, they were revoked in England in 1660 when the Anglican Church was reinstated with the restoration of Charles II. [8]

This approach to Christmas was not well received by the populace. Apprentices who lost their day off rioted in London against shop owners who complied with keeping their shops open in non-observance of the holiday. Some homes and even a few Puritan churches continued to decorate for Christmas. The declared Puritan days of fasts and thanksgivings never captured the hearts and imaginations of the people or produced a communal feeling like the religious festivals had. The denial of such entertainments only led to increased noncompliance and resentment against Puritan leaders. [13]

This approach to Christmas was not well received by the populace. Apprentices who lost their day off rioted in London against shop owners who complied with keeping their shops open in non-observance of the holiday. Some homes and even a few Puritan churches continued to decorate for Christmas. The declared Puritan days of fasts and thanksgivings never captured the hearts and imaginations of the people or produced a communal feeling like the religious festivals had. The denial of such entertainments only led to increased noncompliance and resentment against Puritan leaders. [13]  Noting that the choice of the date and manner of the Christmas celebration had more to do with the pagan solstice celebrations than Christ’s actual birth date which Rev. Thorowgood and others had concluded was likely in the spring, Thorowgood expressed willingness to accept another date and manner of celebrating the birth:

Noting that the choice of the date and manner of the Christmas celebration had more to do with the pagan solstice celebrations than Christ’s actual birth date which Rev. Thorowgood and others had concluded was likely in the spring, Thorowgood expressed willingness to accept another date and manner of celebrating the birth:

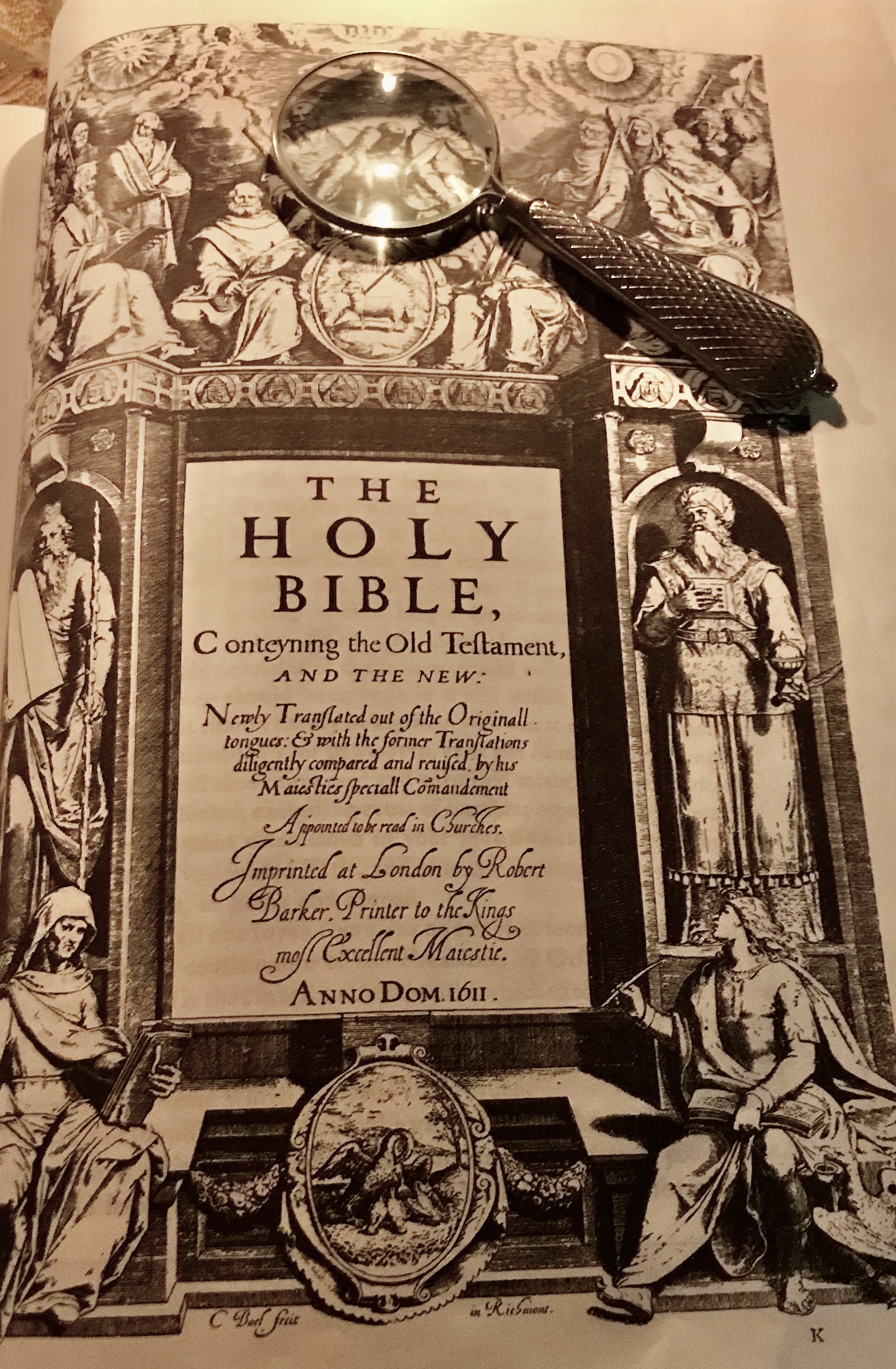

In 1589, John Aylmer, who became Bishop of London, declared that “God is English.” That same year Richard Hakluyt glorified the efforts of English colonization in North America to spread the “true” religion. In 1610, William Crashaw preached that England and the struggling Virginia colonists were “the friend of God.” The Protestant English of the 17th century believed they were now God’s chosen people and that, like the Israelites of the Old Testament, God intended them to possess this new promised land. [3]

In 1589, John Aylmer, who became Bishop of London, declared that “God is English.” That same year Richard Hakluyt glorified the efforts of English colonization in North America to spread the “true” religion. In 1610, William Crashaw preached that England and the struggling Virginia colonists were “the friend of God.” The Protestant English of the 17th century believed they were now God’s chosen people and that, like the Israelites of the Old Testament, God intended them to possess this new promised land. [3]

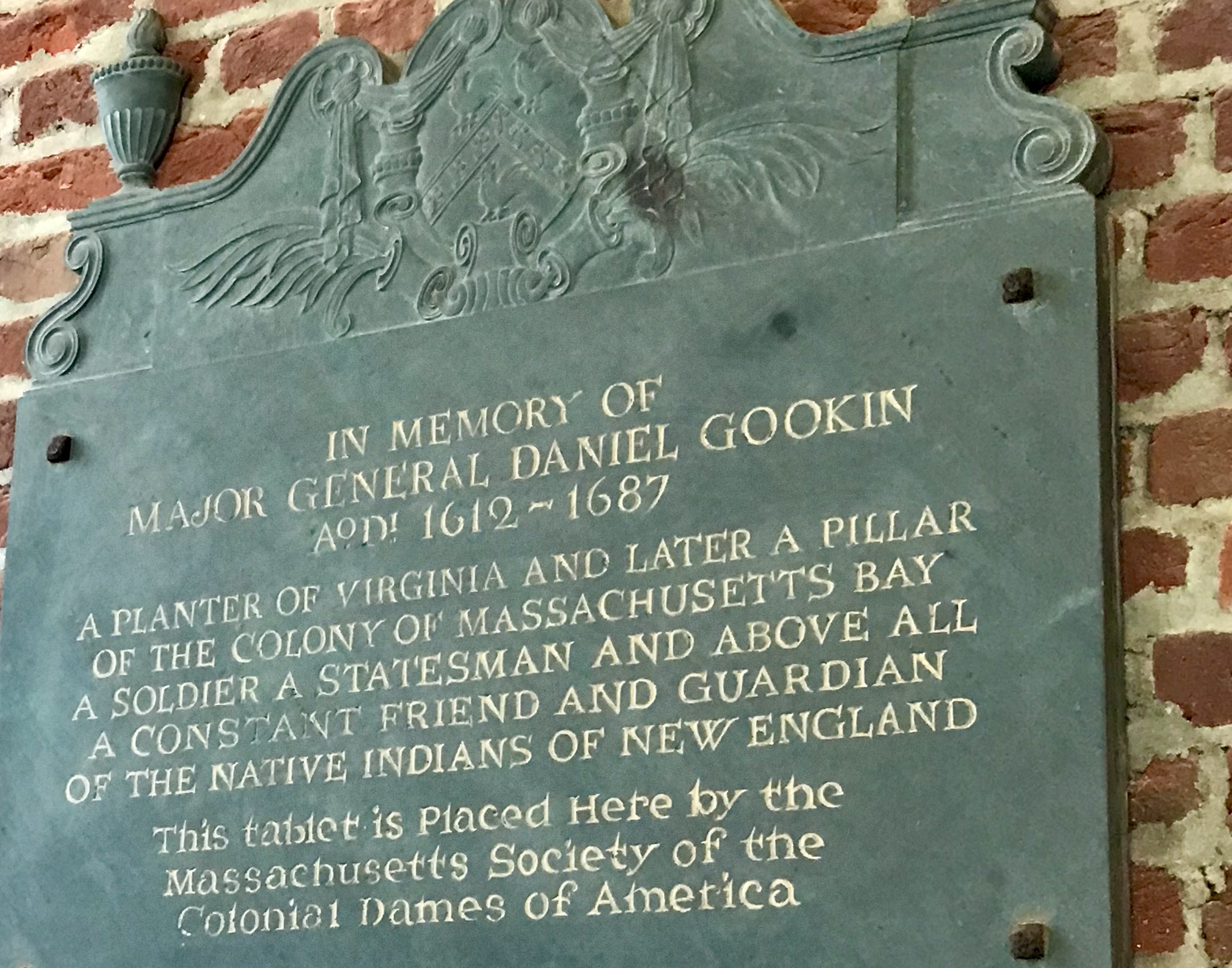

As noted in the last post, Daniel Gookin, Richard Bennett, and 69 others from the Nansemond area requested ministers from Puritans in New England in May 1642. Their letter was received favorably by the elders of Christ Church in Boston and, after consideration, three suitable ministers were sent to Virginia: William Tompson, John Knowles, and Thomas James. Wanting to be respectful of the Virginian leaders, they arrived with a letter of introduction from Gov. Winthrop to Virginia’s relatively new Gov. William Berkeley. Although the Assembly initially seemed pleased that colonists had successfully solicited ministers, Berkeley did not welcome them. However, many Virginians responded to their religious fervor. It was reported they “preached openly unto the people for some space of time, and also from house to house exhorted the people daily that they would cleave unto the Lord; the harvest they had was plentiful for the little space of time they were there.” Knowles reported, “The people’s hearts were inflamed with desire to hear them.” [18]

As noted in the last post, Daniel Gookin, Richard Bennett, and 69 others from the Nansemond area requested ministers from Puritans in New England in May 1642. Their letter was received favorably by the elders of Christ Church in Boston and, after consideration, three suitable ministers were sent to Virginia: William Tompson, John Knowles, and Thomas James. Wanting to be respectful of the Virginian leaders, they arrived with a letter of introduction from Gov. Winthrop to Virginia’s relatively new Gov. William Berkeley. Although the Assembly initially seemed pleased that colonists had successfully solicited ministers, Berkeley did not welcome them. However, many Virginians responded to their religious fervor. It was reported they “preached openly unto the people for some space of time, and also from house to house exhorted the people daily that they would cleave unto the Lord; the harvest they had was plentiful for the little space of time they were there.” Knowles reported, “The people’s hearts were inflamed with desire to hear them.” [18]

The conflict became particularly heated in the Elizabeth River Parish of Lower Norfolk County when the popular Puritan Rev. Harrison was charged with nonconformity in 1645 by the Anglican justices of a divided county court. When Harrison left and went to the welcoming Nansemond parishes, William Durand, an unordained minister, began to preach Puritan doctrine in his stead, but was arrested, and his unauthorized flock was told to disperse. Puritan Cornelius Lloyd, a Lower Norfolk Burgess, and his brother Edward Lloyd, a former Burgess, came to Durand’s defense which resulted in them being accused as “abettors to much sedition and mutiny.” In 1648, Berkeley and his council banished Harrison and Durand from the colony. That next year when Charles I was deposed, Virginia Puritans appealed to the English Parliamentary Council of State who ordered Berkeley to reinstate the Rev. Harrison, but he had already left for New England and never returned. [20]

The conflict became particularly heated in the Elizabeth River Parish of Lower Norfolk County when the popular Puritan Rev. Harrison was charged with nonconformity in 1645 by the Anglican justices of a divided county court. When Harrison left and went to the welcoming Nansemond parishes, William Durand, an unordained minister, began to preach Puritan doctrine in his stead, but was arrested, and his unauthorized flock was told to disperse. Puritan Cornelius Lloyd, a Lower Norfolk Burgess, and his brother Edward Lloyd, a former Burgess, came to Durand’s defense which resulted in them being accused as “abettors to much sedition and mutiny.” In 1648, Berkeley and his council banished Harrison and Durand from the colony. That next year when Charles I was deposed, Virginia Puritans appealed to the English Parliamentary Council of State who ordered Berkeley to reinstate the Rev. Harrison, but he had already left for New England and never returned. [20]

Another important trader on the Chesapeake was the Dutch merchant Simon Overzee who married Adam and Sarah Thorowgood’s daughter Sarah and moved from Virginia to St. Mary’s County in the 1650s. The Thorowgood’s daughter Ann married Job Chandler, a friend of the Maryland governor, and also moved to Maryland in 1651. With the increasing persecution in Virginia, ultimately about 300 Puritan men, women, and children decided to leave their homes in Virginia in the 1650s. These Virginians established the town Providence, now known as Annapolis, in Maryland where they received fertile land as well as “the liberty of our consciences in matter of religion and all other privileges of English subjects.” Ironically, the Act of Toleration that had initially protected those Puritans was repealed when they took over the Maryland government in 1652, but it was reinstated in 1657. [22]

Another important trader on the Chesapeake was the Dutch merchant Simon Overzee who married Adam and Sarah Thorowgood’s daughter Sarah and moved from Virginia to St. Mary’s County in the 1650s. The Thorowgood’s daughter Ann married Job Chandler, a friend of the Maryland governor, and also moved to Maryland in 1651. With the increasing persecution in Virginia, ultimately about 300 Puritan men, women, and children decided to leave their homes in Virginia in the 1650s. These Virginians established the town Providence, now known as Annapolis, in Maryland where they received fertile land as well as “the liberty of our consciences in matter of religion and all other privileges of English subjects.” Ironically, the Act of Toleration that had initially protected those Puritans was repealed when they took over the Maryland government in 1652, but it was reinstated in 1657. [22]

Cromwell’s Commonwealth ended shortly after his death, and by the time King Charles II ascended to the throne, Berkeley had been returned as Virginia’s governor. Berkeley was less strident in his persecution of religious dissidents in his second term, but faced other challenges building to Bacon’s Rebellion in 1675.

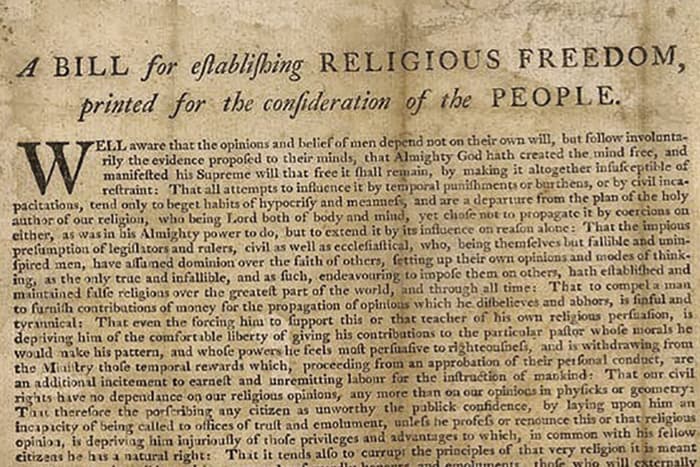

Cromwell’s Commonwealth ended shortly after his death, and by the time King Charles II ascended to the throne, Berkeley had been returned as Virginia’s governor. Berkeley was less strident in his persecution of religious dissidents in his second term, but faced other challenges building to Bacon’s Rebellion in 1675.  Under Bishop Compton’s commissaries, Virginia became more solidly Anglican in the 18th century. Persecution continued against nonconformists who expanded to include Presbyterians, Baptists, and Methodists. It was not until the throes of the American Revolution that Thomas Jefferson’s bill The Virginia Statute for Establishing Religious Freedom, was proposed, although it was not passed by the Virginia Assembly until 1786. At last there was separation of church and state, and Virginians were free to select their own faith without coercion or persecution. [26]

Under Bishop Compton’s commissaries, Virginia became more solidly Anglican in the 18th century. Persecution continued against nonconformists who expanded to include Presbyterians, Baptists, and Methodists. It was not until the throes of the American Revolution that Thomas Jefferson’s bill The Virginia Statute for Establishing Religious Freedom, was proposed, although it was not passed by the Virginia Assembly until 1786. At last there was separation of church and state, and Virginians were free to select their own faith without coercion or persecution. [26]

Likely inspired by them, Daniel Gookin Sr. had an approved proposal to bring cattle out of Ireland to Virginia by November 1620, and in July 1621, he asked the Council to be granted a plantation as large as was given to William Neuce. Daniel Gookin Sr. arrived in Virginia from Ireland in November 1621 on the Flying Harte to the acclaim of the Virginia Council:[5]

Likely inspired by them, Daniel Gookin Sr. had an approved proposal to bring cattle out of Ireland to Virginia by November 1620, and in July 1621, he asked the Council to be granted a plantation as large as was given to William Neuce. Daniel Gookin Sr. arrived in Virginia from Ireland in November 1621 on the Flying Harte to the acclaim of the Virginia Council:[5]

Good real estate often stays good real estate. The site that Daniel Gookin Sr. chose on the James River not far from the confluence with the Nansemond River is today covered by the Newport News shipyard (America’s largest industrial shipbuilder) and a terminus for the largest coal exporting site in the U.S. While nothing of Marie’s Mount remains to be found, a small window opened between 1928 and 1935 when a Newport News physician, Jerome Knowles, found a large exposed 17th century trash pit on the eroding banks of the James River in the area of Marie’s Mount. Dr. Knowles eventually donated the artifacts to Iver Noel Hume, the director of archaeology for Colonial Williamsburg, where the collection still resides. Dr. Hume noted the artifacts were from the 2nd quarter of the 17th century (the Gookin era) and stated there was “the finest group of Pisa marbled slipwares that I have seen or heard of from any other site.” The quantity and type of artifacts in this happenstance collection seemed to be in line with the presence of around 30-50 people at the Gookin site. [8]

Good real estate often stays good real estate. The site that Daniel Gookin Sr. chose on the James River not far from the confluence with the Nansemond River is today covered by the Newport News shipyard (America’s largest industrial shipbuilder) and a terminus for the largest coal exporting site in the U.S. While nothing of Marie’s Mount remains to be found, a small window opened between 1928 and 1935 when a Newport News physician, Jerome Knowles, found a large exposed 17th century trash pit on the eroding banks of the James River in the area of Marie’s Mount. Dr. Knowles eventually donated the artifacts to Iver Noel Hume, the director of archaeology for Colonial Williamsburg, where the collection still resides. Dr. Hume noted the artifacts were from the 2nd quarter of the 17th century (the Gookin era) and stated there was “the finest group of Pisa marbled slipwares that I have seen or heard of from any other site.” The quantity and type of artifacts in this happenstance collection seemed to be in line with the presence of around 30-50 people at the Gookin site. [8]

John ultimately acquired 1490 acres, including 640 acres in Lower Norfolk County adjoining the Thorowgood estate in October 1641 after his marriage to Sarah Thorowgood. This land came to him for transporting 13 persons, which included 7 unnamed negroes. John and Daniel Gookin also patented land on the Rappahannock River along with Richard Bennett and other neighbors from the Nansemond region, although neither were resident there. [11]

John ultimately acquired 1490 acres, including 640 acres in Lower Norfolk County adjoining the Thorowgood estate in October 1641 after his marriage to Sarah Thorowgood. This land came to him for transporting 13 persons, which included 7 unnamed negroes. John and Daniel Gookin also patented land on the Rappahannock River along with Richard Bennett and other neighbors from the Nansemond region, although neither were resident there. [11]

While most government officials and Jamestown residents remained staunchly Anglican and tried to enforce adherence to the official religion, there were dissensions in Virginia as well as England in this pre-English Civil War era. The Munster area in Ireland that the Gookins came from was also known to have Puritan connections. Puritan influence in Virginia became particularly strong in Upper and Lower Norfolk and on the Eastern Shore. Richard Bennett, a friend and neighbor of the Gookins, went on to become the first Governor under the Puritan Commonwealth Era government.[14]

While most government officials and Jamestown residents remained staunchly Anglican and tried to enforce adherence to the official religion, there were dissensions in Virginia as well as England in this pre-English Civil War era. The Munster area in Ireland that the Gookins came from was also known to have Puritan connections. Puritan influence in Virginia became particularly strong in Upper and Lower Norfolk and on the Eastern Shore. Richard Bennett, a friend and neighbor of the Gookins, went on to become the first Governor under the Puritan Commonwealth Era government.[14]

As would be expected under the legal concept of coverture, John Gookin took financial responsibility for the Thorowgood estate after the marriage. He pursued debt collection and represented the Thorowgood heirs in land matters in court. After his marriage, John stepped out of his older brother’s shadow and was quickly elevated to responsible positions and accorded increased status. Thomas Willoughby and John Gookin agreed to jointly build a store at Willoughby Point for the benefit of the community. John later was designated to provide a ferry at Lynnhaven on the lands of the Thorowgood heirs. “John Gookin’s Landing,” referred to in later deeds, was on Samuel Bennett’s Creek near the site called Ferry where the Old Donation Church was built. John was reported to represent Lower Norfolk County in the Assembly in 1640. [18]

As would be expected under the legal concept of coverture, John Gookin took financial responsibility for the Thorowgood estate after the marriage. He pursued debt collection and represented the Thorowgood heirs in land matters in court. After his marriage, John stepped out of his older brother’s shadow and was quickly elevated to responsible positions and accorded increased status. Thomas Willoughby and John Gookin agreed to jointly build a store at Willoughby Point for the benefit of the community. John later was designated to provide a ferry at Lynnhaven on the lands of the Thorowgood heirs. “John Gookin’s Landing,” referred to in later deeds, was on Samuel Bennett’s Creek near the site called Ferry where the Old Donation Church was built. John was reported to represent Lower Norfolk County in the Assembly in 1640. [18]

The first jury trial in Lower Norfolk County also concerned John Gookin. Whereas fellow justices generally had no qualms about passing judgment on cases involving their peers, they decided that using a jury of 12 men provided the “most equitable way” in this matter. As noted in a prior post, the hogs belonging to Capt. John Gookin escaped their pen and damaged the corn field of his neighbor Richard Foster. As Gookin had installed sturdy fencing to try to keep his hogs in and Foster had none to keep animals out, the jury found for Gookin. At that time, planters were expected to fence in their plants if they wanted to protect them from roaming animals. [20]