What were you thinking, Adam Thorowgood? Why did you do it?

Recorded in the land records of the Lower County of New Norfolk on February 8, 1637, Captain Adam Thorowgood was granted “150 acres, due for transportation of 3 Negroes.”2 Adam had become a success by 1637. He arrived in Virginia in 1621 as a 17-year-old indentured servant eager to learn the skills of a successful planter. He married well, recruited his own indentured servants, became a planter-merchant, was elected a Burgess, and was appointed to the Governor’s Council. Through good management of his affairs, he secured the largest land grant at that time in Lower Norfolk (Virginia Beach), and, with his English family connections, he even received a recommendation from the King’s Privy Council. He had achieved all that by age 33 without owning a single enslaved person. He had acquired his land and wealth through providing opportunities for willing English workers to come to Virginia– until that February.1

Adam Thorowgood, by then a Captain in the local militia, had transported over 100 English headrights whose names were recorded. Unlike his white indentured servants, the unnamed Africans had not willingly agreed to pay for their passage with their labor. His purchase appeared as an insignificant entry in the 17th century land records, yet it was a pivotal life moment. How seriously did Adam consider his decision? As the son of a minister, did his soul wrestle with a moral decision or was it a business decision based on “others are doing it?” As three more workers and 150 acres were not critical to his success and there were few Africans in the Colony, was it done for status? being part of the next new trend? “wise” planning for the future?

Virginia’s First Africans

The first Africans arrived in Virginia in August 1619 before the Pilgrims or New England Puritans ever stepped foot in North America. They arrived, not bringing their hopes for freedom from oppression and dreams of unlimited possibilities, but with sadness for their lost homes and liberty as well as fear for the future. The United States recently commemorated 400 years since the first Africans were brought to Point Comfort (Hampton), Virginia, aboard the White Lion commanded by an English privateer John Jope. The White Lion along with the Treasurer, which was owned by the Earl of Warwick, had attacked the Portuguese slave ship St. John de Baptiste which was carrying 350 African captives to Veracruz, Spanish America.

The captains took around 60 of the Africans as booty, of which the White Lion, arriving in Virginia, “brought not anything but 20, and odd Negroes which the Governor [Yeardley] and Cape Merchant bought for vituals…at the best and easiest rates they could.”3 It was a significant moment in the history of the Colony of Virginia and the future United States of America. Their descendants and those of later enslaved persons brought here have been part of the fabric and story of this nation ever since. The descendants of those from Africa are as American as Mayflower descendants who came from England.

Enslaved or Indentured?

When Captain Thorowgood and the early Virginians looked at the world around them, they likely saw what they considered justification. Although Virginia had been the first permanent English colony founded, it was not the first to be brought captured Africans. The first Negro was taken to English Bermuda in 1616, only three years after the settlement of that island. In 1619, when Virginia got its first twenty or so, Bermuda had nearly 100 Black Africans, who, having been captured from slave ships, continued in bondage.4

In Bermuda and Virginia, a few Black Africans were fortunate to have time-limited service and were granted or able to buy their freedom. Some historians have suggested that the status of Africans in Virginia was initially unclear as there were no official laws about slavery until the 1660s, and they should be considered indentured, not enslaved. However, as early as 1623, Bermuda passed a law forbidding Negros from having firearms, which Virginia seemed to copy in 1640 legislating that “all persons, except Negroes” should be provided with arms and ammunition. In 1630, English Barbados passed a law that “Negros … who came here to be sold should serve for life unless a contract was before made to the contrary.” English racism and slavery had taken root.5

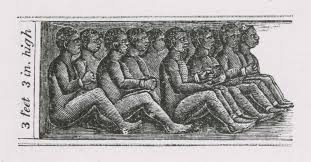

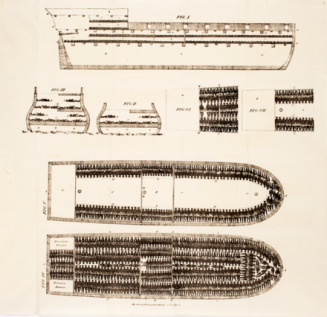

Slavery, though, is not just defined by the term of service, but also the conditions under which a person is placed in bondage. No one was going all the way to Africa or even the Caribbean to recruit voluntary indentured servants for Virginia. Persons from Africa were not offered options for time- limited contracts while in their home countries nor did they request transport to the Americas on slave ships. The White Lion and Treasurer were not on humanitarian rescue missions to free those they pirated from the slave ship, but rather sought to profit from them. Slave ship captains brought captured Africans to the Americas against their wills in the most horrendous conditions and sold them to labor involuntarily without recompense or opportunity to return to their homes. That is slavery, whether it was for a few years, a lifetime, or perpetual; whether they were treated kindly or harshly; whether housed with white servants or in slave quarters; whether or not the term “slave” was yet in the legal code or even if they were accorded a few rights.6

Trans-Saharan and East African Slave Trade

The English and early Virginians, though, were not the inventors of African slavery. Centuries before Columbus “discovered” America, Arabs and Ottoman Turks, forbidden from enslaving fellow Muslims, had been capturing sub-Saharan Africans for forced labor in Africa or transporting them as enslaved laborers and servants to the Persian Gulf and Arabian Penninsula.

While the triangle trade of tobacco, sugar, and slaves spanned the Atlantic in the 17th and 18th centuries, there was also the trans-Saharan and East African trade in gold, salt, spices, ivory, and slaves with major slave markets in the Nile Basin and on Zanzibar Island in the Indian Ocean. It has been estimated that at least 9 million Africans were taken in the East African slave trade which did not end until into the 20th century.7

Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade

Portuguese mariners started to sell Black African slaves in Lagos, Portugal, 50 years before Columbus sailed and quickly expanded their trade further into the Western Mediterranean and islands off the African coast. By the early 16th century, they were also sending enslaved persons to colonies in the Americas. Most of the 5.8 million enslaved Africans transported by the Portuguese had short lives in the sugar plantations of Brazil and the Caribbean. Although records of the Spanish trans-Atlantic trade are sketchy, it is now believed the Spanish may have taken at least 1.5 million Africans to their Spanish colonies.8

The Dutch were early participants in the slave trade and brought about a million captured Africans across the Atlantic between 1596 to 1829 to their sugar plantations in Dutch Guiana, the Caribbean, and other colonies. The French were also significant slave traders, bringing more than a million enslaved Africans to their Caribbean islands, particularly Saint-Domingue (Haiti). Even the Prussians and Danes joined in the slave trade in the 17th through 19th centuries. 9

English Slave Trade

Being late to colonization, the English were late to enter the African slave trade, but ultimately became the second largest group of slave traders. In the 1560s, Queen Elizabeth I authorized Sir John Hawkins to engage in slave trading directly with Africa, taking around 1,300 Africans to the Spanish Caribbean over 4 voyages to exchange for pearls and other commodities. However, it proved more profitable for English privateers to simply prey on Spanish and Portuguese slaving ships, as with the White Lion and Treasurer. In 1631, the Guinea Company of London merchants were granted rights by King Charles I to trade with West Africa. This was revitalized and reformed into the Royal African Company in 1672 under King Charles II. It is estimated that between 1640-1807, the British transported 3.1 million Africans to the Caribbean, North and South America, and other countries.10

The number of Africans brought to Virginia in the first half of the 17th century was relatively small compared to the number of white English indentured servants. However, as it became harder to entice English laborers to Virginia, planters increasingly turned to using enslaved African workers. By 1650, there were about 300 enslaved persons in Virginia. By 1700, there were 6,000. Virginia became a slave society, dependent on their slave labor. By 1860, the slave population in the United States had expanded to almost 4,000,000 of which about 500,000 lived in Virginia.11

Slavery in New England

In the popular narrative of Colonial American history, slavery is viewed as a Southern sin. However, New England Puritans not only profited from the slave trade early on, but some owned and financed slave ships as well as had enslaved servants and laborers. In 1638, the year after Thorowgood made his purchase, the Salem-based ship Desire took a group of captured Native Americans to the West Indies to exchange for the first shipload of enslaved Negros to be brought to New England.

In 1641, Massachusetts was the first colony to enact a law regarding the parameters of slavery. By midcentury, there were actually more enslaved Africans in the Northern colonies than in the Chesapeake region, although that rapidly changed. In the Boston vicinity, many families transitioned from primarily using white indentured servants to enslaved Africans during the 17th century. However, as in all eras, there were those who embraced humanity, such as Samuel Sewall, the author of the first New England anti-slavery pamphlet, The Selling of Joseph, in 1700, which declared that even slaves, “are the Offspring of God, and have equal Right unto Liberty….” 12

Accountability

Overall, the total number of enslaved Africans imported to the areas that became the United States of America was around 600,000. This was only about 5% of the estimated 12 million enslaved Africans brought to North and South America in the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Despite the great migration of white Europeans across the Atlantic from 1580-1700, there were even more who arrived in the Americas in those years as enslaved Africans. However, as the Black population expanded in the colonies, the number of enslaved individuals who were bought and sold in the intercolonial trade soon exceeded those brought from afar. 13

Slavery would not have spread across the world, though, without some complicit Africans. Portugal engaged in war in Angola, but most Europeans waited for captured Africans to be brought to the coasts. Prisoners from wars between kingdoms and tribal groupings were sold by enemy groups. In addition, greedy and cruel mercenaries raided rural villages and sophisticated cities to capture and sell Blacks for profit. Countless men, women, and children died in the raids, wars, and horrific marches across Africa to the sea coasts. Many of those who survived then died in the slave ships during the Middle Passage voyage across the Atlantic. Trying to grasp the breath and depth of seventeenth century slavery through this post is not intended to shift or lessen anyone’s responsibility, but rather to extend accountability. 14

Concept of Equality

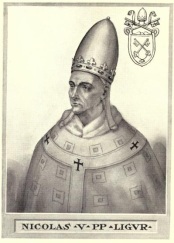

How could Adam Thorowgood and other decent people of his time not see the shared humanity of the enslaved? Through the 17th century, most Europeans and non-Europeans did not believe all men were equal or that liberty was a God-given right. The concept of equality was not championed by prevailing religious, political, or scientific thought. Pope Nicholas V in 1452 sanctioned Portuguese Christians to “vanquish” and “reduce their [black Gentiles] persons to perpetual slavery…” as a means of conversion and controlling barbarians. Protestant, especially Calvinistic, thought at the time believed men were predestined to their station in life and saw divine providence in the hierarchical social structure. Many New England Puritans, including Governor Winthrop, did not oppose enslaving Africans or Native Americans. Science focused on differentiating species and subspecies which some extended to humanity and the idea of race “inferiority.”15

John Locke, the influential English philosopher, proposed in 1689 that men had a natural right to life, liberty, and property, despite he himself having stock in slave trading companies. Gradually through the 17th and 18th centuries, these principles gained greater acceptance, even if they were not yet inclusive of all mankind/womankind. The American Founding Fathers, while imperfect in their own understandings, attitudes, and actions, were extraordinary and revolutionary in using ideals, not persons or heredity, to create a national government based on principles of equality and liberty. Unfortunately, these rights were not extended to all. We still need to improve.16

John Locke, the influential English philosopher, proposed in 1689 that men had a natural right to life, liberty, and property, despite he himself having stock in slave trading companies. Gradually through the 17th and 18th centuries, these principles gained greater acceptance, even if they were not yet inclusive of all mankind/womankind. The American Founding Fathers, while imperfect in their own understandings, attitudes, and actions, were extraordinary and revolutionary in using ideals, not persons or heredity, to create a national government based on principles of equality and liberty. Unfortunately, these rights were not extended to all. We still need to improve.16

Slavery in New Norfolk, Virginia

Adam Thorowgood was not the only one in New Norfolk, Virginia, to own Africans. Argoll Yeardley, the elder son of Governor Yeardley, received his land grant in New Norfolk on February 6, 1637 by including “Andolo and Maria 2 Negroes.” On May 18, 1637, John Wilkins also received land there for importing a Negro. Between 1638 and 1650, at least 33 Africans were purchased in Lower Norfolk County. Among those, Francisco, Emanuell, Antonyo, Lewis, and Maria were sold to Francis Yeardley, Argoll’s younger brother and the third husband of Adam’s widow, Sarah Thorowgood Gookin Yeardley, “to possess and peaceably enjoy…for ever.” A few years later in 1653, Argoll Yeardley sold to John Custis, recently arrived in Northampton, Virginia, his first enslaved person, a girl named Doll. The terms were explicit that Custis was to “have and to hold her and her increase forever.” Although this all occurred before the 1660 slavery laws, this was classic slavery.17

Legacies

I have found no evidence that Adam Thorowgood himself purchased more than his initial three Africans. He died only three years later in 1640. In his will, Adam did not enumerate the names of or differentiate between his servants, but gave them all to his wife and minor children.18 I will discuss their further family entanglements with slavery in future posts. While some of Adam and Sarah’s descendants continued to own enslaved persons until the Emancipation, others had already willingly freed theirs. Some of their descendants moved North and fought and died as Union soldiers; others supported the Confederacy. The complexity of Adam and Sarah Thorowgood’s legacy is evidenced as one descendant, Mary Anna Randolph Custis, married Robert E. Lee and another, Julia Dent, married Ulysses S. Grant.

I wish I could travel back in time to change the course of history and warn Adam Thorowgood and others not to open that door to slavery. However, neither I, nor any of us, can alter the past, although we can seek to better understand and learn from it. In my time, I can oppose injustice and seek to make my community, my nation, and my world more inclusive, more kind, and more fair as we strive harder for liberty and justice for all. I wish the world could have understood earlier how much Black lives really do matter.

Upcoming Post: Envisioning the Invisible: Thorowgood’s First Home in Lynnhaven, Virginia

- McCartney, Martha W., Virginia Immigrants and Adventurers 1607-1635 (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 2007), 691-692. ↩

- Nugent, Nell Marion, Cavaliers and Pioneers: Abstracts of Virginia Land Patents and Grants, 1623-1800, v. I (Richmond: Dietz Printing Co., 1934), 79. ↩

- Horn, James, 1619: Jamestown and the Forging of American Democracy (New York: Basic Books, 2018), 85-88. ↩

- Jarvis, Michael J., “Bermuda and the Beginnings of Black Anglo-America,” Virginia 1619: Slavery and Freedom in the Making of English America, Paul Musselwhite, Peter C. Mancall and James Horn eds. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2019), 114-115, 125. ↩

- Horn, 103, 112-114, 239. Jarvis, 125. Billings, Warren M., The Old Dominion in the Seventeenth Century (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007), 173-178. ↩

- Horn, 107-108. Morgan, Philip D., “Virginia Slavery in Atlantic Context, 1550 to 1650,”Virginia 1619: Slavery and Freedom in the Making of English America, Paul Musselwhite, Peter C. Mancall and James Horn eds. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2019), 86. ↩

- McDougall, E. Ann, “The Caravel and the Caravan,” The Atlantic World and Virginia: 1550-1624, Peter C. Mancall, ed. (Chapel Hill: The University or North Carolina Press, 2007), 143-149. Horn, 92-94. Koigi, Bob, “Forgotten Slavery: The Arab-Muslim Slave Trade,” Fair Planet Dossier. Accessed online on August 27, 2020 at fairplanet.org/dossier ↩

- Horn, 92-94. Northrup, David, ” The Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic World,” The Atlantic World and Virginia: 1550-1624, Peter C. Mancall, ed. (Chapel Hill: The University or North Carolina Press, 2007), 174, 227. Davis, David Brion, Slavery in the Colonial Chesapeake (Williamsburg, Virginia: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1986), 2-4. Low Country Digital History Initiative of the College of Charleston, “African Laborers for a New Empire: Iberia, Slavery, and the Atlantic World.” Accessed online August 21, 2020 at ldhi.library.cofc.edu ↩

- “Dutch Slave Trade” and “French Slave Trade,” Slavery and Remembrance: A Guide to Sites, Museums and Memory, (Williamsburg, Virginia; The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 2020). Accessed online on 8/18, 2020 at slaveryandremembrance.org. Eltis, David, The Rise of African Slavery in the Americas (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 37-38, 121-122. Boucher, Philip P., “Revisioning the French Atlantic,”Virginia 1619: Slavery and Freedom in the Making of English America, Paul Musselwhite, Peter C. Mancall and James Horn eds. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2019), 302-304. Weindl, Andrea, “The Slave Trade of Northern Germany from the Seventeenth to the Nineteenth Centuries,” Extending the Frontiers, Yale Scholarship Online. Accessed 8/15/20 at yale.universitypressscholarship.com ↩

- Eltis, 61-62. Morgan, 102-104. The National Archives, “Britain and the Slave Trade.” Accessed online 8/ 14/20 at nationalarchives.gov.uk ↩

- Billings, 173. Morgan, 85-87. “Virginia Slave Population Map, 1860,” Shaping the Constitution: Resources from the Library of Virginia and the Library of Congress. Accessed online on 9/8/2020 at edu.lva.virginia.gov. ↩

- Warren, Wendy, New England Bound: Slavery and Colonization in Early America (New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2016), 7, 11-12; 221-222. Whiting, Gloria McCahon, ” Race, Slavery, and the Problem of Numbers in Early New England,” The William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd ser. 77:3 (July 2020), 424-427. ↩

- Eltis, 11. O’Malley, Gregory E., Final Passages: The Intercolonial Slave Trade of British America, 1619-1807 (Chapel Hill: The University ofNorth Carolina Press, 2014). “Slavery in the United States” Accessed online at en.wikipedia.org on 8/5/2020. ↩

- Eltis, 59-60, 147-151. Horn, 115-116. ↩

- Horn, 105- 107. LDHI online. Davis, David Brion, The Problem of Slavery in the Age of Revolution 1770-1823 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 42-44. Warren, 31-33. ↩

- Davis, Problem of Slavery, 45-47. Eltis, 15-18. Douglass, Frederick, “The Constitution of the United States: Is it Pro-Slavery or Anti-Slavery?” presented at the Scottish Anti-Slavery Society in Glasgow, Scotland on March 26, 1860. Accessed online on September 15, 2020 at blackpast . Uzgalis, William, “John Locke, Racism, Slavery, and Indian Lands,” abstracted from The Oxford Handbook of Philosophy and Race. Accessed 8/18/20 at Oxford Handbooks Online: Scholarly Research Reviews at oxfordhandbooks.com ↩

- Billings, 223. Horn, 111-112. Morgan, 86. Nugent, 53, 75, 81. Walczyk, Frank V., Northampton County, Virginia Orders and Wills 1698-1710, vol II 1704-1710 (Coram, New York: Peter’s Row, 2001), 7, 128. ↩

- “The Thorowgood Family of Princess Anne County, Va.” The Richmond Standard. 26 November 1882 ↩

This was my puzzlement–the curiosity that started my research and blog. How did a twenty-two-year-old young man raised in Norfolk, England, having just spent four years working as an indentured servant in Virginia, suddenly show up in London and, within a year, marry the daughter of a wealthy merchant who was also a granddaughter and great-granddaughter of Lord Mayors of London? In the Big Bang Theory of life, how did these two very different orbits ever come crashing into each other? The marriage of Adam Thorowgood to Sarah Offly was recorded in the parish register of St. Anne’s Blackfriars, London, on July 18, 1627.

This was my puzzlement–the curiosity that started my research and blog. How did a twenty-two-year-old young man raised in Norfolk, England, having just spent four years working as an indentured servant in Virginia, suddenly show up in London and, within a year, marry the daughter of a wealthy merchant who was also a granddaughter and great-granddaughter of Lord Mayors of London? In the Big Bang Theory of life, how did these two very different orbits ever come crashing into each other? The marriage of Adam Thorowgood to Sarah Offly was recorded in the parish register of St. Anne’s Blackfriars, London, on July 18, 1627.

William Thorowgood was born around 1560 in Felsted, Essex, but moved to Grimston, Norfolk around 1585 when he married Anne Edwards of Norwich, Norfolk, and accepted the post as the Vicar of St. Boltolph’s Church. All of William’s nine children were born in Grimston. Reverend Thorowgood was honored by being appointed as the commissary for the Bishop of Norwich. William came from an armorial family. Although not needed for his position with the church, he received “a confirmation of this Armes and Crest” in March 1620.

William Thorowgood was born around 1560 in Felsted, Essex, but moved to Grimston, Norfolk around 1585 when he married Anne Edwards of Norwich, Norfolk, and accepted the post as the Vicar of St. Boltolph’s Church. All of William’s nine children were born in Grimston. Reverend Thorowgood was honored by being appointed as the commissary for the Bishop of Norwich. William came from an armorial family. Although not needed for his position with the church, he received “a confirmation of this Armes and Crest” in March 1620.  Robert Offley II and his wife, Anne Osbourne, were both born in London. Robert was a “Turkey merchant” with the Levant Company (traders with the Ottomans) whose first Governor was his father-in-law, Sir Edward Osborne. Osborne had been knighted and had been a Lord Mayor of London (like his father-in -law William Hewitt).

Robert Offley II and his wife, Anne Osbourne, were both born in London. Robert was a “Turkey merchant” with the Levant Company (traders with the Ottomans) whose first Governor was his father-in-law, Sir Edward Osborne. Osborne had been knighted and had been a Lord Mayor of London (like his father-in -law William Hewitt).  It has sometimes been assumed that Adam’s older brother, Sir John Thorowgood of Kensington, brought the families together based on his position in the court of King Charles I and the erroneous belief that he had been serving as the secretary to William Herbert, Earl of Pembroke, a significant member of the Virginia Company of London. As

It has sometimes been assumed that Adam’s older brother, Sir John Thorowgood of Kensington, brought the families together based on his position in the court of King Charles I and the erroneous belief that he had been serving as the secretary to William Herbert, Earl of Pembroke, a significant member of the Virginia Company of London. As

Sarah and her sisters might have been even more daring than her brothers. They likely had watched with interest as the Virginia Company had recruited “young, handsome, and honestly-educated Maids” to send to the Colony in 1620-21 on “bride ships” to establish families and bring greater stability and order to colonial society. These women were as much “adventurers” as their male counterparts.

Sarah and her sisters might have been even more daring than her brothers. They likely had watched with interest as the Virginia Company had recruited “young, handsome, and honestly-educated Maids” to send to the Colony in 1620-21 on “bride ships” to establish families and bring greater stability and order to colonial society. These women were as much “adventurers” as their male counterparts.

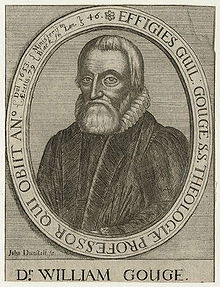

Sarah and Adam would certainly have been familiar with Reverend William Gouge’s famous sermon “Of Domestical Duties” delivered there in 1622 which was considered a “text” on family life in that era. In the hierarchical structure popular in that age, Reverend Gouge saw a wife as above her children, but below her husband who was to be “as a Priest unto his wife…. He is as a king in his owne house.”

Sarah and Adam would certainly have been familiar with Reverend William Gouge’s famous sermon “Of Domestical Duties” delivered there in 1622 which was considered a “text” on family life in that era. In the hierarchical structure popular in that age, Reverend Gouge saw a wife as above her children, but below her husband who was to be “as a Priest unto his wife…. He is as a king in his owne house.”

Shakespeare, himself, had his heroine Juliette pose the question, “What is in a name?” (Romeo and Juliette) In this case, the name seems to be the issue on which the verdict hangs. Everyone basically agreed that the sailor Edward Samuel was killed with a shovel by another sailor with the last name of Waters in a dispute shortly after the shipwreck on Bermuda. He then hid on the island and refused to join the other passengers when they finally sailed to Virginia in 1610.

Shakespeare, himself, had his heroine Juliette pose the question, “What is in a name?” (Romeo and Juliette) In this case, the name seems to be the issue on which the verdict hangs. Everyone basically agreed that the sailor Edward Samuel was killed with a shovel by another sailor with the last name of Waters in a dispute shortly after the shipwreck on Bermuda. He then hid on the island and refused to join the other passengers when they finally sailed to Virginia in 1610.

In the Muster, Edward Waters was living in Elizabeth Cittie and listed as the head of the household. He was reported to have 37 barrels of corn and 1500 dry fish (far more than his neighbors); no livestock (very few had any); 1 boat, 4 houses/buildings, and 1 palisade; 10 pounds of powder, 100 pounds of lead, 11″pieces” (muskets?), 1 pistol, 6 swords, and 4 “armors and coates.” Edward Waters gave his age as 40 and stated he had arrived in Virginia on the Patience, having left England in 1608. He had actually embarked on the SeaVenture in 1609, but with the Julian calendar still in use in England, it would have been only a few months into that new year.

In the Muster, Edward Waters was living in Elizabeth Cittie and listed as the head of the household. He was reported to have 37 barrels of corn and 1500 dry fish (far more than his neighbors); no livestock (very few had any); 1 boat, 4 houses/buildings, and 1 palisade; 10 pounds of powder, 100 pounds of lead, 11″pieces” (muskets?), 1 pistol, 6 swords, and 4 “armors and coates.” Edward Waters gave his age as 40 and stated he had arrived in Virginia on the Patience, having left England in 1608. He had actually embarked on the SeaVenture in 1609, but with the Julian calendar still in use in England, it would have been only a few months into that new year.

That does not mean that Edward Waters’ conduct was spotless. He was ready to resort to violence with Edward Chard over disputes regarding the ambergris. He also chose to join the shady voyage to the West Indies for “supplies” which Richard Norwood refused to be part of. That group of 32 from Bermuda were never designated as pirates or privateers, although they did attack and capture a Portuguese vessel while they were “off-course” in the Canary Islands, had an encounter with a French pirate, and later were rescued after another shipwreck on a deserted isle by an unnamed English pirate.

That does not mean that Edward Waters’ conduct was spotless. He was ready to resort to violence with Edward Chard over disputes regarding the ambergris. He also chose to join the shady voyage to the West Indies for “supplies” which Richard Norwood refused to be part of. That group of 32 from Bermuda were never designated as pirates or privateers, although they did attack and capture a Portuguese vessel while they were “off-course” in the Canary Islands, had an encounter with a French pirate, and later were rescued after another shipwreck on a deserted isle by an unnamed English pirate.

At the end of the first month, the first of the counselors, Caldicott, persuaded thirty-two others, including Edward Waters and Edward Chard, to go with him to the West Indies for “supplies” (loot). Richard Norwood, the surveyor, wrote in his diary:

At the end of the first month, the first of the counselors, Caldicott, persuaded thirty-two others, including Edward Waters and Edward Chard, to go with him to the West Indies for “supplies” (loot). Richard Norwood, the surveyor, wrote in his diary: