Jamestown. October 16, 1629. The General Assembly of the Colony of Virginia convened consisting of 46 elected representatives from 24 designated sites along with Governor John Pott and his Councillors. It had been ten years since the House of Burgesses with its twenty-two representatives from 11 localities had met under the leadership of the newly appointed governor, Sir George Yeardley, becoming the first representative legislative assembly in the Americas.1 In the intervening years, the Colony had pulled through the devastation of the Powhatan Uprising and the dissolution of its founding commercial Virginia Company of London. The Colony had not only survived, but prospered. In 2019, the Commonwealth of Virginia celebrated the 400th anniversary of the beginning of representative government in America. Did the Burgesses in 1629 happen to pause to acknowledge its tenth anniversary?

The burgesses that year would have been aware that their situation was tenuous. The election of representatives began while the Colony was under the private chartered Virginia Company of London. After the Company was dissolved and Virginia was designated a Royal Colony in 1624, the House of Burgesses was neither sanctioned nor disallowed by King Charles I. Virginians, though, had taken to the idea of elected representation, and, despite the uncertainty, the General Assembly still met. 2 Still, continuation of a representative assembly was not assured. Ironically, while the Virginia representatives met in 1629, Charles I, weary of not getting the monies and approvals he wanted, dissolved England’s Parliament. He did not call it back into session until 1640, a time in English history known as “The Eleven Year Tyranny.” 3 The citizens in England in that period were denied their representative voice.

The Vision of a Commonwealth

The commission that was carried to the Colony in 1619 by Governor Yeardley changed the course of Virginia’s government and ultimately that of the United States of America. It reflected an important step in the English philosophical debate about how nations and colonies should be governed. In the 15th and 16th century, some judicial philosophers put forward the idealized concept of a nation as a “common-weal” where a harmonious hierarchical balance would be maintained between the monarchy, the government, and the people in such a way that all would share in a common well-being. To achieve this would require an enlightened monarch, a responsive and responsible government, and a represented and diligent populace, all of them living in accordance with the righteous principles and laws of the Church. 4

Although the basic components of a commonwealth existed in 17th century England (King, Parliament, Church, and the People), they were not harmoniously united, and the initial governments of Jamestown were chaotic and authoritarian. The harsh implementation of the Company’s initial “Lawes Divine, Moral, and Martial” by its governors had not fostered shared prosperity or unity in Virginia. With the Colony still struggling, the Virginia Company changed leadership, and Sir Edwin Sandys, a proponent of the commonwealth concept, was elected a director.

Sir Edwin Sandys, A Founding Father

Sandys and his supporters desired for Virginia to become a New World commonwealth that would benefit all those living there and involve them in their own public affairs. He believed in strengthening the economy by diversification of crops and production, increasing emigration through land incentives, allowing free trade, providing representation in government, and converting the native peoples to Anglican Protestantism after which they surely would happily assume their place in this harmonious, supportive hierarchy. He saw Virginia as the opportunity to create “a perfected English society.” However, Virginia was not a blank slate. The Powhatan Indians were not interested in becoming loyal Protestant subjects of James I. Colonists already had a taste of wealth through tobacco and did not want to diversify. The offer of land ownership and a voice in one’s governance, though, were attractive incentives to increase emigration. 5

Sir Edwin Sandys also had his difficulties with the Crown. Considered the most influential member of the House of Commons at the time, he was in frequent conflict with King James I. In 1621, he was even placed under house arrest related to his contrary opinion on the “Spanish marriage” being considered for Prince Charles. Sandys never proposed a commonwealth without a monarch, but he supported a powerful Parliament. Perceiving his democratic tendencies, Capt. John Bargrave attacked the Virginia commonwealth project saying, “the mouth of equal liberty must be stopped.” 6

Today, while one of the fifty states, Virginia is still officially named The Commonwealth of Virginia. The noted Jamestown historian, Dr. James Horn, summarized Sandys’s contribution as an unrecognized early Founding Father thus: 7

Sandys’s dream of creating a commonwealth in the interests of settlers and Indians proved short-lived. But the twin-pillars of democracy–the rule of law and representative government–survived and flourished. It was his greatest legacy to America.

Challenges of Creating a General Assembly

While the concept of an elected governmental body was exciting to the early colonists, there were challenges in its implementation. It was easily decided that the Assembly would meet in the choir seats of the largest and finest building in Jamestown, its new church built in 1617, but how to conduct the meeting was a greater challenge. Only John Pory, the Secretary of the Colony, had ever had legislative experience as a member of the House of Commons in Parliament, so he was authorized as the Speaker of the House. Still, it was uncertain what a colonial legislative body of a private company could or should do. Was it to be more of an advisory appendage to handle local matters for the Company or could it actually formulate laws for the Colony and become a type of “Little Parliament?” 8

Until 1643, the General Assembly was a unicameral body intended to convene annually with the Governor, his Councillors, and the elected Burgesses all meeting and working together. According to the instructions, Sir George Yeardley was to establish ” a laudable form of Magistracy and just Laws…for the happy guiding and governing of the people.” With little direction from England, no experience in drafting laws, and a whole new set of circumstances to regulate, Virginians began to craft their own unique government, setting themselves on a twisting and rocky path that would ultimately lead to independence.9

17th Century Voting and Representation

Among those newly elected Burgesses in 1629 was Adam Thorowgood of Elizabeth City, whose life regular readers of this blog know I am tracking through the 17th Century. It is rather remarkable that he was elected at that point, for it was only four years since he had finished his indentureship to Edward Waters, and Elizabeth City was a large and important settlement. However, much had transpired in those years to boost his prominence. Likely using the £100 inheritance from his father, Adam purchased 150 acres and was recognized as a “gentleman of Kikotan. ” He then returned to England and married into the influential and wealthy merchant families of the Osbournes and Offleys. Around that time, his older brother, John Thorowgood, was appointed a Gentleman of the Bed Chamber for King Charles (like Ladies in Waiting for a Queen) and was anticipating knighthood. Although only 24 years old when he returned to Virginia in 1628, Adam Thorowgood was a young man of which to take note. So, who would have been able to vote to elect him a Burgess? 10

In the beginning, to vote for a Burgess one had only to be a free man of age (21) who gave allegiance to England. Today we equate representation with being able to cast a vote. It was construed differently at that time. The first Africans were brought to Virginia a month after the Burgesses first met in 1619, but their arrival was unanticipated. (future posts) The restriction on being free was not originally intended to exclude slaves, but to keep bound indentured servants from voting who might be unduly pressured by their temporary “owners.” Masters were viewed as representing their bound and enslaved servants.11

Most adult women were considered under the concept of “feme covert.” If unmarried and living at home, she was considered represented by her father. If married, her husband was to represent her and their children. Only widowed or independent single women (“feme sole”) had no “representation” in this system. With men outnumbering women in the Colony for its first century, women were usually not single for long. Adam Thorowgood’s wife, Sarah, though, became a formidable widow even without the vote. 12

Initially, it was easier for a man to qualify to vote in Virginia than in England. Just as what was happening in England influenced Virginia, what Virginia did influenced the direction of events in England. There were efforts in the House of Commons during this same period to broaden England’s parliamentary franchise, but they were unsuccessful. Unfortunately, with time, more restrictions were added to Virginia’s voting requirements. In 1670, around the period the Assembly was passing restrictive race-related laws, they added the requirement that one had to to own land or property to vote.13

Out of concern over the increasing number of free blacks within the Colony and fear they might join in a slave insurrection, the Assembly passed a law in 1723 “That no free negro, mulatto, or Indian whatsoever, hereafter have any vote at the election of burgesses, or any other election whatsoever.” Another right was curtailed. After Bacon’s rebellion in 1676, the King had begun to exert more control over Virginia, so even the elected legislature began to lose some of its freedoms and independence.14

The Legislative Agendas 1629-1632

During the years Adam Thorowgood participated as a Burgess, the Assembly dealt with some significant changes as well as rather provincial matters. In his first session in 1629, the Burgesses considered the usual issues of planting corn, going against the Indians, planting tobacco, penalties for not going to church, paying for tithables, and the refortification of Point Comfort.15

Discussions might have been a bit more interesting in the following session on March 24, 1629/30 (using the Julian calendar). Sir John Harvey had just been appointed governor to replace John Pott, who was accused of stealing cattle (he was convicted in July). The Assembly passed Acts prohibiting price gouging and defrauding by sea merchants and colonists, ordering farmers to grow at least 2 acres of corn per worker, forbidding the killing of female cows until they were post-breeding, and, as colonists had renewed attacks on the Indians, allowing “noe peace bee concluded with them.” Act 5, though, was more unusual. After asking each household to preserve their wood ashes for the making of potash, the following was requested: 16

Discussions might have been a bit more interesting in the following session on March 24, 1629/30 (using the Julian calendar). Sir John Harvey had just been appointed governor to replace John Pott, who was accused of stealing cattle (he was convicted in July). The Assembly passed Acts prohibiting price gouging and defrauding by sea merchants and colonists, ordering farmers to grow at least 2 acres of corn per worker, forbidding the killing of female cows until they were post-breeding, and, as colonists had renewed attacks on the Indians, allowing “noe peace bee concluded with them.” Act 5, though, was more unusual. After asking each household to preserve their wood ashes for the making of potash, the following was requested: 16

ACT V

…every master of a family shall have a special care…to preserve and keepe all their urine which shall be made…they shall receave directions the benefit whereof…shall redounde to those that shall make the experiment…

How the urine was to be collected and stored and the means of the Act’s enforcement were not explained. Indeed, there was much the Burgesses still needed to learn about the fine art of practical legislation. However, urine could be used as the source of potassium nitrate which, combined with manure and a few other ingredients and allowed to age for 10 months, could produce gunpowder. Or you could just order more ready-made from England.

In contrast, the sessions in 1631-32 were groundbreaking as the Assembly decided to review, consolidate, revise, void when needed, and reform the body of laws that had accumulated over the years. This was their first attempt to develop and publish a consistent Code of Law for the Colony. The first review appeared to have taken place by only a partial Assembly as it included only 20 Burgesses representing 13 combined districts and started meeting on February 21, 1631/32. They produced a document of 68 acts which included 15 related to Church matters. Not surprisingly, the “urine collection” regulation did not survive the review. 17

In contrast, the sessions in 1631-32 were groundbreaking as the Assembly decided to review, consolidate, revise, void when needed, and reform the body of laws that had accumulated over the years. This was their first attempt to develop and publish a consistent Code of Law for the Colony. The first review appeared to have taken place by only a partial Assembly as it included only 20 Burgesses representing 13 combined districts and started meeting on February 21, 1631/32. They produced a document of 68 acts which included 15 related to Church matters. Not surprisingly, the “urine collection” regulation did not survive the review. 17

While Adam Thorowgood was not in the February meetings, he was present a few months later on September 4, 1632 when the entire group of 37 Burgesses from all 25 sites met to consider the work that had been done. With some changes to the earlier revision for clarity and convenience, the Assembly then issued 61 Acts. The Preamble stated: 18

we doe therefore herby ordeyne and establish that these acts and orders… be published in this colony and to be accounted and adjudged in force. And all other acts and orders of any assembly heretofore holden to be voyd and of none effect.

While there would be many more revisions in the years to come, that year Virginians confidently took ownership of their legislative process.

Coming Post: Thorowgood’s Return: Competing for Emigrants for 17th Century Virginia

Footnotes:

- Hening, William Waller, The Statutes at Large Being a Collection of all the Laws of Virginia from the First Session of the Legislature in the Year 1619, vol. I (New York: R.W. & G. Bartow, 1823), 132-33. Accessed online at books. google on May 15, 2020. McIlwaine, H.R. and J.P. Kennedy, eds., Journal of the House of Burgesses of Virginia I: 1619-1658-59. (Virginia, General Assembly, 1915), 2-3; 52 137. Accessed online at books.google on May 15, 2020. ↩

- Billings, Warren M., The Old Dominion in the Seventeenth Century: A Documentary History of Virginia, 1607-1700 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007), 52. ↩

- Crofton, Ian, The Kings and Queens of England (London: Quercus, 2006), 162-163. ↩

- Horn, James, 1619: Jamestown and the Forging of American Democracy (New York: Basic Books, 2018), 121-123. ↩

- Ibid., 127-131, 153. Rabb, Theodore K. “Sir Edwin Sandys (1561–1629).” Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Humanities, 18 Feb. 2014. Web. 18 May. 2020. ↩

- Horn, 8. ↩

- Ibid., 217. ↩

- Ibid., 68-69. Billings, Warren M., A Little Parliament: The Virginia General Assembly in the Seventeenth Century (Richmond: The Library of Virginia, 2004), xvi-xix, 160. ↩

- Billings, Little Parliament, 16-17. Horn, 60, 67-68, 81, 160. ↩

- McCartney, Martha W., Virginia Immigrants and Adventurers 1607-1635 (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., Inc., 2007), 168. Matthew, H. C. G., and Brian Harrison ed., “Thoroughgood, John” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 54 (London: Oxford University Press, 2004), 660-662. ↩

- Billings, Little Parliament, 18, 55, 160. ↩

- Billings, Old Dominion, 360-361. Parramore, Thomas C., Peter C. Stewart, and Tommy L. Bogger, Norfolk: The First Four Centuries (Charlottesville: Univeristy Press of Virginia, 1994), 26-28, 39-42. ↩

- Horn, 208. Bushman, Richard, “English Franchise Reform in the Seventeenth Century,” The Journal of British Studies, III (November 1963), 36-38. Accessed online on May 10, 2020 at http://www.jstor.org/stable/pdfplus/175047.pdf. Requirements for Voting in Virginia, 1670-1850 from Virginia Places. Accessed online May 2, 2020 at http://www.virginiaplaces.org/government/voteproperty.html ↩

- Wolfe, Brendan. “Free Blacks in Colonial Virginia.” Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Humanities, 13 May. 2019. Web. 19 May. 2020. ↩

- Hening, 145. ↩

- Ibid., 149-152 ↩

- Ibid., 153. ↩

- Ibid., 178-180. Billings, Little Parliament, 193-194. ↩

Easter has long been regarded as the most important of the Holy Days for Christians. In medieval times, the faithful would prepare by consuming fish, but abstaining from all meat and dairy for 40 days in the observance of Lent. Holy Week started with Palm Sunday and proceeded through Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, Holy Saturday, and finally culminated in Resurrection Sunday with great feasting and festivity. As with Christmas, some pagan aspects were adopted, especially symbols associated with new life and fertility, such as rabbits, eggs, and new chicks.

Easter has long been regarded as the most important of the Holy Days for Christians. In medieval times, the faithful would prepare by consuming fish, but abstaining from all meat and dairy for 40 days in the observance of Lent. Holy Week started with Palm Sunday and proceeded through Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, Holy Saturday, and finally culminated in Resurrection Sunday with great feasting and festivity. As with Christmas, some pagan aspects were adopted, especially symbols associated with new life and fertility, such as rabbits, eggs, and new chicks.  As eggs were also one of the forbidden foods in Lent, they were often in great abundance at the Easter Day feast. There was also likely to be roast lamb, replacing the Passover lamb of the Last Supper with the symbol of Christ as the unblemished Lamb of God. In 1407, the Bishop of Salisbury and his 80 guests consumed two lambs as well as venison, veal, beef, pigs and piglets, 20 capons, 48 chickens, and more than 500 eggs!

As eggs were also one of the forbidden foods in Lent, they were often in great abundance at the Easter Day feast. There was also likely to be roast lamb, replacing the Passover lamb of the Last Supper with the symbol of Christ as the unblemished Lamb of God. In 1407, the Bishop of Salisbury and his 80 guests consumed two lambs as well as venison, veal, beef, pigs and piglets, 20 capons, 48 chickens, and more than 500 eggs!  Maundy Thursday, named for the mandatum or commandment given by Christ at the Last Supper to love others, had been associated with humility and the washing of the feet of the poor since the fourth century. King John started the English tradition of the monarch giving gifts in 1210 by him donating clothing, forks, food, and other gifts to the poor. In 1213, he gave small silver coins. By 1363, Edward III was both giving coins and washing the feet of selected poor. Nobles were also known to have held their own Maundy distributions, but not necessarily at Easter.

Maundy Thursday, named for the mandatum or commandment given by Christ at the Last Supper to love others, had been associated with humility and the washing of the feet of the poor since the fourth century. King John started the English tradition of the monarch giving gifts in 1210 by him donating clothing, forks, food, and other gifts to the poor. In 1213, he gave small silver coins. By 1363, Edward III was both giving coins and washing the feet of selected poor. Nobles were also known to have held their own Maundy distributions, but not necessarily at Easter.  The decorating and gifting of eggs was an ancient tradition in many cultures. Eggs became a Christian symbol of the resurrection with elaborate decoration particularly popular in the Germanic and Eastern Orthodox churches. Coloring eggs was also adopted in England. The household accounts for Edward I in 1307 included “18 pence for 450 eggs to be boiled and dyed or covered with gold leaf and distributed to the Royal household.”

The decorating and gifting of eggs was an ancient tradition in many cultures. Eggs became a Christian symbol of the resurrection with elaborate decoration particularly popular in the Germanic and Eastern Orthodox churches. Coloring eggs was also adopted in England. The household accounts for Edward I in 1307 included “18 pence for 450 eggs to be boiled and dyed or covered with gold leaf and distributed to the Royal household.”

Although most colonists did not come to Virginia seeking religious freedom or with intense religious zeal, there was greater diversity of religious beliefs and practices in the early years than is often recognized. Archaeological evidence at the Jamestown fort has revealed that there were some secret Catholics in the fort. The first Puritans in America settled in Virginia years before a group traveled together to Massachusetts in 1630. Adam Thorowgood seemed to have had Puritan leanings himself, as his brother, Thomas, became a noted Puritan preacher in England, and Adam and his wife Sarah had married in a Puritan congregation in England. Sarah’s second husband, John Gookin, was from a staunch early Puritan family. Later, even Quakers established themselves in Virginia. Dissidents would later be forced to leave.

Although most colonists did not come to Virginia seeking religious freedom or with intense religious zeal, there was greater diversity of religious beliefs and practices in the early years than is often recognized. Archaeological evidence at the Jamestown fort has revealed that there were some secret Catholics in the fort. The first Puritans in America settled in Virginia years before a group traveled together to Massachusetts in 1630. Adam Thorowgood seemed to have had Puritan leanings himself, as his brother, Thomas, became a noted Puritan preacher in England, and Adam and his wife Sarah had married in a Puritan congregation in England. Sarah’s second husband, John Gookin, was from a staunch early Puritan family. Later, even Quakers established themselves in Virginia. Dissidents would later be forced to leave.

Lent was probably observed, ending with an Easter feast, though not as elaborate as in England. As the Elizabeth Cittie Parish remained firmly Anglican, except unwittingly during the Commonwealth era, Easter Communion would have been offered and probably Palm Sunday celebrated. I have found no references to other special services during Holy Week in this era in Virginia, although they may have been held. As on other Sundays, they would have likely followed their tradition of “tarrying” before and/or after church, as it was one of the few occasions when the settlers could gather casually with friends and distant neighbors. At the second church site, the finding of numerous pipe stems of the period is evidence of leisure gatherings.

Lent was probably observed, ending with an Easter feast, though not as elaborate as in England. As the Elizabeth Cittie Parish remained firmly Anglican, except unwittingly during the Commonwealth era, Easter Communion would have been offered and probably Palm Sunday celebrated. I have found no references to other special services during Holy Week in this era in Virginia, although they may have been held. As on other Sundays, they would have likely followed their tradition of “tarrying” before and/or after church, as it was one of the few occasions when the settlers could gather casually with friends and distant neighbors. At the second church site, the finding of numerous pipe stems of the period is evidence of leisure gatherings.

At the time the English arrived, the Indians at Kecoughtan were a small group living in about 18 homes (yi-hakans) under the Powhatan chiefdom. They had once been a larger tribe, but were conquered by Chief Powhatan in 1597/8 . At the time of the landing, Pochins, a son of Powhatan, was their leader. Captain John Smith later traded with the Kecoughtans (forcibly) for corn and spent a pleasant and memorable Christmas season where “we were never more merry nor fed on more plentie of good oysters, fish, flesh, and wild fowle and good bread, nor never had better fires in England than in the dry smoky houses of Kecoughten.”

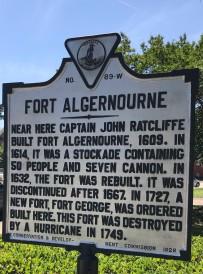

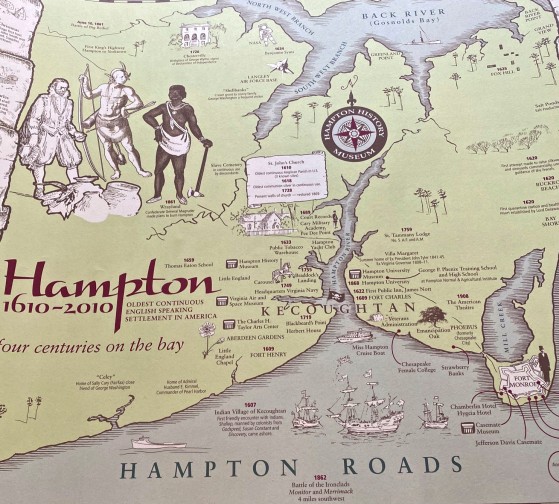

At the time the English arrived, the Indians at Kecoughtan were a small group living in about 18 homes (yi-hakans) under the Powhatan chiefdom. They had once been a larger tribe, but were conquered by Chief Powhatan in 1597/8 . At the time of the landing, Pochins, a son of Powhatan, was their leader. Captain John Smith later traded with the Kecoughtans (forcibly) for corn and spent a pleasant and memorable Christmas season where “we were never more merry nor fed on more plentie of good oysters, fish, flesh, and wild fowle and good bread, nor never had better fires in England than in the dry smoky houses of Kecoughten.” The English quickly realized the importance of this Indian territory to control access to the James River. By October 1609, George Percy, as leader of the colony, ordered Fort Algernourne built near Cape Comfort (today’s Fort Monroe). With greater access to fresh water and food sources, those stationed there survived the 1609/10 Starving Time far better than those at Jamestown. However, they made no attempt to rescue Jamestown, but, rather, some secretly planned to return to England.

The English quickly realized the importance of this Indian territory to control access to the James River. By October 1609, George Percy, as leader of the colony, ordered Fort Algernourne built near Cape Comfort (today’s Fort Monroe). With greater access to fresh water and food sources, those stationed there survived the 1609/10 Starving Time far better than those at Jamestown. However, they made no attempt to rescue Jamestown, but, rather, some secretly planned to return to England.

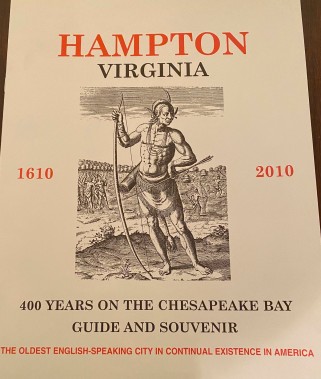

This “cittie” originally included much of the area south of Jamestown, but should not be confused with today’s Elizabeth City in North Carolina. For many years, part of the area was still called Kecoughtan, especially near Indian Thicket where their village once stood. There are streets, a high school, and shopping places that continue to carry the name. Ironically, Cape “Comfort” became the site where the first “twenty or odd” Africans were brought to the colony on the privateer vessel The White Lion and traded for supplies in 1619. In 1620, the English in Kecoughtan numbered 28 men, 12 women, and 14 children.

This “cittie” originally included much of the area south of Jamestown, but should not be confused with today’s Elizabeth City in North Carolina. For many years, part of the area was still called Kecoughtan, especially near Indian Thicket where their village once stood. There are streets, a high school, and shopping places that continue to carry the name. Ironically, Cape “Comfort” became the site where the first “twenty or odd” Africans were brought to the colony on the privateer vessel The White Lion and traded for supplies in 1619. In 1620, the English in Kecoughtan numbered 28 men, 12 women, and 14 children.

As early as 1617, the Virginia Company sent over some French colonists to try growing grape vines in a beach area they called Buckroe. In 1620 they tried the cultivation of silk worms without much success. Still, there were 30 colonists living in Buckroe in 1623. Over the years, this Chesapeake Bay beach in Hampton became best known for its production of recreational fun.

As early as 1617, the Virginia Company sent over some French colonists to try growing grape vines in a beach area they called Buckroe. In 1620 they tried the cultivation of silk worms without much success. Still, there were 30 colonists living in Buckroe in 1623. Over the years, this Chesapeake Bay beach in Hampton became best known for its production of recreational fun.

Kecoughton/ Elizabeth Cittie quickly developed into a proper town. An Anglican parish had been established in July 1610, making St. John’s Episcopal Church in Hampton “the oldest active, English-speaking congregation in the Americas.” The site of the initial church building is unknown, but the second church whose foundations have been found on the Hampton University grounds was built around 1624. Adam and Sarah Thorowgood and their neighbors would have worshipped there. Several of the upright (or uptight?) men and women of this town were involved in bringing accusations in the first witchcraft trial in the English colonies against Joan Wright who had lived in Kecoughtan .

Kecoughton/ Elizabeth Cittie quickly developed into a proper town. An Anglican parish had been established in July 1610, making St. John’s Episcopal Church in Hampton “the oldest active, English-speaking congregation in the Americas.” The site of the initial church building is unknown, but the second church whose foundations have been found on the Hampton University grounds was built around 1624. Adam and Sarah Thorowgood and their neighbors would have worshipped there. Several of the upright (or uptight?) men and women of this town were involved in bringing accusations in the first witchcraft trial in the English colonies against Joan Wright who had lived in Kecoughtan . In the early 1620s, Captain Thomas Neuce, the manager of the Virginia Company of London lands, built two guest houses for the reception of new immigrants when they first arrived. William Capps offered to build one on the west side of the river in 1623 to help with the influx of persons. However, hospitality took a step up when James Knott in 1632 leased land “desiring to keepe a house of entertainment…whereby strangers and others my bee well accommodated…the howse commonly called the great howse.” John Potts, the Virginia governor who was disgraced and discharged in 1630 for stealing cattle, was among those known to enjoy the entertainment (which was a respectable term) in Kecoughtan.

In the early 1620s, Captain Thomas Neuce, the manager of the Virginia Company of London lands, built two guest houses for the reception of new immigrants when they first arrived. William Capps offered to build one on the west side of the river in 1623 to help with the influx of persons. However, hospitality took a step up when James Knott in 1632 leased land “desiring to keepe a house of entertainment…whereby strangers and others my bee well accommodated…the howse commonly called the great howse.” John Potts, the Virginia governor who was disgraced and discharged in 1630 for stealing cattle, was among those known to enjoy the entertainment (which was a respectable term) in Kecoughtan.

There are no actual buildings that remain in Hampton, or the rest of Virginia, from the second quarter of the 17th century when Adam and the others lived there. Archaeological studies have found that homes both for the wealthy and the common folk were built from the abundant timber in a post-in-ground earthfast manner which did not survive long in Virginia’s climate and soil. In 1986-87, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation’s Department of Archaeological Research conducted follow-up investigations of an early 17th century site at Hampton University. They found evidence of an early two-bay house of wood and mud possibly from the 1620s that was followed by other houses within 10-15 years “embellished with glass windows, possibly a tile roof, a passage, and a brick-lined cellar.” The artifacts found at the site suggested a “relatively high-status colonial residence,” and they were comparable in the quality, quantity, and point of origin to those found at the capital Jamestown. These findings seem to correlate with economic and societal progress of Elizabeth Cittie.

There are no actual buildings that remain in Hampton, or the rest of Virginia, from the second quarter of the 17th century when Adam and the others lived there. Archaeological studies have found that homes both for the wealthy and the common folk were built from the abundant timber in a post-in-ground earthfast manner which did not survive long in Virginia’s climate and soil. In 1986-87, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation’s Department of Archaeological Research conducted follow-up investigations of an early 17th century site at Hampton University. They found evidence of an early two-bay house of wood and mud possibly from the 1620s that was followed by other houses within 10-15 years “embellished with glass windows, possibly a tile roof, a passage, and a brick-lined cellar.” The artifacts found at the site suggested a “relatively high-status colonial residence,” and they were comparable in the quality, quantity, and point of origin to those found at the capital Jamestown. These findings seem to correlate with economic and societal progress of Elizabeth Cittie. Like most of the early landowners, Adam Thorowgood bought additional tracts of land. While his purchases were never in dispute, there was extensive litigation over some land claims, particularly in the original areas designated as “company lands” by the Virginia Company. Some colonists had already settled in the areas of Strawberry Banks and Mill Creek, and there were muddled and contested claims after the Company was dissolved in 1624.

Like most of the early landowners, Adam Thorowgood bought additional tracts of land. While his purchases were never in dispute, there was extensive litigation over some land claims, particularly in the original areas designated as “company lands” by the Virginia Company. Some colonists had already settled in the areas of Strawberry Banks and Mill Creek, and there were muddled and contested claims after the Company was dissolved in 1624.

Did I forget to mention that the head of Blackbeard, the Pirate, was placed on a spike on the James River in 1718 to adorn the entrance to Hampton and scare off the pirates?

Did I forget to mention that the head of Blackbeard, the Pirate, was placed on a spike on the James River in 1718 to adorn the entrance to Hampton and scare off the pirates? Or that the first Southern reading of the Emancipation Proclamation was done under the Emancipation Oak in Hampton?

Or that the first Southern reading of the Emancipation Proclamation was done under the Emancipation Oak in Hampton?

A headright to the British Colonies in the 17th Century was someone whose passage was paid for by another person who in turn received a land grant, typically of 50 acres, for each person brought as an effort to encourage sponsorship of emigrants. The headright was then expected to repay his or her passage, usually through labor as an indentured servant for 4-7 years. Augustine Warner was among the first 35 individuals recruited as headrights by the newly wed Adam and Sarah Thorowgood in England. Augustine accompanied them to Virginia in the Hopewell in 1628.

A headright to the British Colonies in the 17th Century was someone whose passage was paid for by another person who in turn received a land grant, typically of 50 acres, for each person brought as an effort to encourage sponsorship of emigrants. The headright was then expected to repay his or her passage, usually through labor as an indentured servant for 4-7 years. Augustine Warner was among the first 35 individuals recruited as headrights by the newly wed Adam and Sarah Thorowgood in England. Augustine accompanied them to Virginia in the Hopewell in 1628.

Adam Thorowgood brought more headrights than he would have needed to work his own land in 1628, so he would likely have followed the custom of selling indentured contracts to other planters. It is not known where Augustine served his indentureship. However, in 1635, a few years after having finished his service, Augustine obtained his first 250 acres of land, based on sponsoring 12 headrights of his own to Virginia. He purchased “one neck of ground called…Pynie Neck…lying at the new Poquoson.”

Adam Thorowgood brought more headrights than he would have needed to work his own land in 1628, so he would likely have followed the custom of selling indentured contracts to other planters. It is not known where Augustine served his indentureship. However, in 1635, a few years after having finished his service, Augustine obtained his first 250 acres of land, based on sponsoring 12 headrights of his own to Virginia. He purchased “one neck of ground called…Pynie Neck…lying at the new Poquoson.”

Augustine Warner remained on the Council until his death on December 24, 1674 at the age of 63. He and his wife Mary were buried in the family cemetery at Warner Hall in Gloucester, Virginia.

Augustine Warner remained on the Council until his death on December 24, 1674 at the age of 63. He and his wife Mary were buried in the family cemetery at Warner Hall in Gloucester, Virginia.

Although no original structures remain of the first Warner Hall built on the Severn River and this plantation was sold out of the family in 1830, the site has continued to be known by the Warner name.

Although no original structures remain of the first Warner Hall built on the Severn River and this plantation was sold out of the family in 1830, the site has continued to be known by the Warner name.

Today

Today

Since Biblical times, good Christians had been taught to fear the Devil and his evil spirits, but around the 14th century, suspicions developed that the odd ones living in their communities might have sold their souls to the Devil and contracted to do his biding.

Since Biblical times, good Christians had been taught to fear the Devil and his evil spirits, but around the 14th century, suspicions developed that the odd ones living in their communities might have sold their souls to the Devil and contracted to do his biding.

As the trial was in September, it is unknown whether Adam had returned to England before the trial started. However, having lived in Kecoughtan the previous years as part of Edward Waters’ household, he may well have known the Wrights or at least heard talk of Joan’s suspicious activities. According to the surviving

As the trial was in September, it is unknown whether Adam had returned to England before the trial started. However, having lived in Kecoughtan the previous years as part of Edward Waters’ household, he may well have known the Wrights or at least heard talk of Joan’s suspicious activities. According to the surviving  Joan Wright had been asked by Lt. Allington, to attend to his pregnant wife as the midwife, but when the wife discovered that Joan was left-handed and heard the rumors about her, she refused her and had another midwife brought. When Goodwife Wright found out, she was upset. The Allingtons believed she therefore cursed them, and consequently, each sequentially became ill (although of different disorders). Even though they all recovered, the infant succumbed after a second illness more than a month after its birth.

Joan Wright had been asked by Lt. Allington, to attend to his pregnant wife as the midwife, but when the wife discovered that Joan was left-handed and heard the rumors about her, she refused her and had another midwife brought. When Goodwife Wright found out, she was upset. The Allingtons believed she therefore cursed them, and consequently, each sequentially became ill (although of different disorders). Even though they all recovered, the infant succumbed after a second illness more than a month after its birth.

The Virginia justices found most of the accusations of witchcraft unsubstantiated. The only guilty verdict that remains is for William Harding of the Northern Neck in Virginia, who was accused by his Scottish preacher of witchcraft and sorcery in 1656. The accusations must not have been too serious, for his punishment was only ten lashes and banishment from the county. Nor were the citizens overly concerned, as he was given two months to leave. Katherine Grady was the only suspected witch to be hung, but it was done before she even reached Virginia in 1654 and under the direction of the ship’s captain, not court justices. When the ship encountered a severe storm near the end of its journey, the passengers were convinced that Katherine had caused it through witchcraft. Upon reaching Jamestown, the Captain had to appear before the admiralty court, but its findings have been lost.

The Virginia justices found most of the accusations of witchcraft unsubstantiated. The only guilty verdict that remains is for William Harding of the Northern Neck in Virginia, who was accused by his Scottish preacher of witchcraft and sorcery in 1656. The accusations must not have been too serious, for his punishment was only ten lashes and banishment from the county. Nor were the citizens overly concerned, as he was given two months to leave. Katherine Grady was the only suspected witch to be hung, but it was done before she even reached Virginia in 1654 and under the direction of the ship’s captain, not court justices. When the ship encountered a severe storm near the end of its journey, the passengers were convinced that Katherine had caused it through witchcraft. Upon reaching Jamestown, the Captain had to appear before the admiralty court, but its findings have been lost. This was put to the test in 1698 when John and Ann Byrd sued Charles Kinsey and John Potts for having “falsely and scandalously” defamed them by claiming they were witches and “in league with the Devil.” Kinsey finally admitted to the court that he might have only dreamed that they “had rid him along the Seaside and home” through witchcraft . John Thorowgood, a son of Adam Thorowgood II, was one of the justices on that court which surprisingly did not give a cash award to the Byrds, but rather found for the defendants. However, they chose not to pursue witchcraft charges against the Byrds.

This was put to the test in 1698 when John and Ann Byrd sued Charles Kinsey and John Potts for having “falsely and scandalously” defamed them by claiming they were witches and “in league with the Devil.” Kinsey finally admitted to the court that he might have only dreamed that they “had rid him along the Seaside and home” through witchcraft . John Thorowgood, a son of Adam Thorowgood II, was one of the justices on that court which surprisingly did not give a cash award to the Byrds, but rather found for the defendants. However, they chose not to pursue witchcraft charges against the Byrds.

In 1705, Elizabeth Hill, another neighbor, called Grace a witch, and a brawl between them ensued. Grace filed a complaint of trespassing and assault and battery against Elizabeth. Although Grace prevailed, she received little in monetary damages. Elizabeth Hill’s husband then made a formal charge of witchcraft against her. Accusations included that no grass would grow where she had danced in the moonlight, that she had soured the cow’s milk, and that she had made herself small enough to fly in an eggshell to England and back in one night to get rosemary seeds for her garden. However, rosemary was abundant locally and, ironically, often used to protect against witches.

In 1705, Elizabeth Hill, another neighbor, called Grace a witch, and a brawl between them ensued. Grace filed a complaint of trespassing and assault and battery against Elizabeth. Although Grace prevailed, she received little in monetary damages. Elizabeth Hill’s husband then made a formal charge of witchcraft against her. Accusations included that no grass would grow where she had danced in the moonlight, that she had soured the cow’s milk, and that she had made herself small enough to fly in an eggshell to England and back in one night to get rosemary seeds for her garden. However, rosemary was abundant locally and, ironically, often used to protect against witches.

Virginia Beach has erected a kindly statue in honor of this misunderstood woman, and the Governor of Virginia recently pardoned her, even though there is no record of her conviction. Grace seems not to have had the sweet disposition portrayed in the statue, but still she serves as a symbol of those innocent “

Virginia Beach has erected a kindly statue in honor of this misunderstood woman, and the Governor of Virginia recently pardoned her, even though there is no record of her conviction. Grace seems not to have had the sweet disposition portrayed in the statue, but still she serves as a symbol of those innocent “

Witchcraft and the occult are still practiced by some today. While there are those who try to connect with the spirit of the earth and be “good witches,” there are others who have carried out horrific acts. Unfortunately, over the ages, many innocents were sent to their deaths because of the superstitions and suspicions of others. It has been estimated that 85% of those killed in European witch hunts were women. A Puritan preacher of the time, William Perkins, was unapologetic in his explanation:

Witchcraft and the occult are still practiced by some today. While there are those who try to connect with the spirit of the earth and be “good witches,” there are others who have carried out horrific acts. Unfortunately, over the ages, many innocents were sent to their deaths because of the superstitions and suspicions of others. It has been estimated that 85% of those killed in European witch hunts were women. A Puritan preacher of the time, William Perkins, was unapologetic in his explanation:

The Virginia Beach History Museum staff had thoughtfully invited not only the descendants of Adam Thorowgood, but also those with Native or African ancestors who might have lived or worked at the site. Generously, they also offered free admission and birthday cake to anyone else who showed up. I thought surely some of the departed ancestors would come for cake and a chance to see how their descendants turned out. However, if they did, they were most discreet, and any missing cake was attributable to hungry guests.

The Virginia Beach History Museum staff had thoughtfully invited not only the descendants of Adam Thorowgood, but also those with Native or African ancestors who might have lived or worked at the site. Generously, they also offered free admission and birthday cake to anyone else who showed up. I thought surely some of the departed ancestors would come for cake and a chance to see how their descendants turned out. However, if they did, they were most discreet, and any missing cake was attributable to hungry guests.

The party celebrated the 300th birthday of the construction of the house. As noted in my

The party celebrated the 300th birthday of the construction of the house. As noted in my  To celebrate, there was dancing on the lawn and children’s activities as well as informative presentations by historian Matthew Laird on “Adam and Sarah Thorowgood–Virginia Beach’s First Power Couple” and on “Finding Your 17th Century Ancestor,” by Donald Moore, a professional genealogist. Although I made contact with some friendly, living Adam Thorowgood descendants and experts, I did not meet any of the haunting kind.

To celebrate, there was dancing on the lawn and children’s activities as well as informative presentations by historian Matthew Laird on “Adam and Sarah Thorowgood–Virginia Beach’s First Power Couple” and on “Finding Your 17th Century Ancestor,” by Donald Moore, a professional genealogist. Although I made contact with some friendly, living Adam Thorowgood descendants and experts, I did not meet any of the haunting kind. Therefore, I decided to take a more direct approach and returned the next week for an evening tour, “Haunted Encounters of the Thoroughgood Kind.” The staff had set the stage for our adventure by serving the guests either witches’ brew or dragon’s blood and cookies while showing the silent movie version of Phantom of the Opera in the waiting area.

Therefore, I decided to take a more direct approach and returned the next week for an evening tour, “Haunted Encounters of the Thoroughgood Kind.” The staff had set the stage for our adventure by serving the guests either witches’ brew or dragon’s blood and cookies while showing the silent movie version of Phantom of the Opera in the waiting area. As we headed across the grounds, our guide became enveloped in fog before we found our way to the gardens. There we were instructed in the proper techniques and herbs to use to protect our houses from evil spirits. Though the house was quiet that evening, the tales of inexplicable encounters and occurrences experienced by reputable staff and guests gave credence to the earlier stories.

As we headed across the grounds, our guide became enveloped in fog before we found our way to the gardens. There we were instructed in the proper techniques and herbs to use to protect our houses from evil spirits. Though the house was quiet that evening, the tales of inexplicable encounters and occurrences experienced by reputable staff and guests gave credence to the earlier stories. There continue to be accounts of the openings of a door bolted from the inside; of noises and shadowy figures; of the man in the brown suit and the woman in the window. In the dim interiors, the 17th century crackled looking glass (mirror) gave back eerie reflections.

There continue to be accounts of the openings of a door bolted from the inside; of noises and shadowy figures; of the man in the brown suit and the woman in the window. In the dim interiors, the 17th century crackled looking glass (mirror) gave back eerie reflections. As I left that evening, a full moon was rising over the darkened house. Was there something hidden in those obscure corners, waiting to come out after the noisy intruders left? I didn’t stay to find out.

As I left that evening, a full moon was rising over the darkened house. Was there something hidden in those obscure corners, waiting to come out after the noisy intruders left? I didn’t stay to find out.

Those reported as dead were Edward Waters, his wife, a child, a maid, and a boy. In the 1624 muster, two children (William and Margaret Waters, “bourne in Virgina”) are listed.

Those reported as dead were Edward Waters, his wife, a child, a maid, and a boy. In the 1624 muster, two children (William and Margaret Waters, “bourne in Virgina”) are listed.

That morning the Powhatan warriors had also been optimistic. They hoped that this would be a mortal blow to this strange (overdressed and smelly) people who had come uninvited to their kingdom, taking their lands and demanding their food, even in times of drought when there was not enough for their own people. Perhaps, these strangers would finally acknowledge their incompetence in surviving in this land, and, defeated, return to their own country. When the English ordered their survivors to abandon their lands and settlements and pull back to secured areas after the attack, the wereoance chiefs must have hoped they had succeeded.

That morning the Powhatan warriors had also been optimistic. They hoped that this would be a mortal blow to this strange (overdressed and smelly) people who had come uninvited to their kingdom, taking their lands and demanding their food, even in times of drought when there was not enough for their own people. Perhaps, these strangers would finally acknowledge their incompetence in surviving in this land, and, defeated, return to their own country. When the English ordered their survivors to abandon their lands and settlements and pull back to secured areas after the attack, the wereoance chiefs must have hoped they had succeeded. Could this conflict have been prevented? As noted above, there are always alternative possibilities. Chief Powhatan himself, knowing the difference between “war and peace better than any” had posed the question to John Smith in 1609, “What will it avail you to take…by force what you may quickly have by love, or to destroy them that provide you food? What can you get by war?”

Could this conflict have been prevented? As noted above, there are always alternative possibilities. Chief Powhatan himself, knowing the difference between “war and peace better than any” had posed the question to John Smith in 1609, “What will it avail you to take…by force what you may quickly have by love, or to destroy them that provide you food? What can you get by war?”  Even if such differences could have been accepted, the two groups would never have been able to meet each other’s expectations or give what the other wanted most. The English wanted land and subservient, Protestant, Indian workers and subjects of King James I. The Powhatans wanted their lands, English weapons, and allies who would work under their Chiefdom to defeat their tribal enemies and protect them. The English considered them false-hearted; to the Powhatans, the English were truce-breakers.

Even if such differences could have been accepted, the two groups would never have been able to meet each other’s expectations or give what the other wanted most. The English wanted land and subservient, Protestant, Indian workers and subjects of King James I. The Powhatans wanted their lands, English weapons, and allies who would work under their Chiefdom to defeat their tribal enemies and protect them. The English considered them false-hearted; to the Powhatans, the English were truce-breakers.  What should this event be called? For centuries, American textbooks called it the Indian or Jamestown “Massacre.” Recently, recognizing the complexities of the conflicts between the English and Powhatans, it has been preferable to call it the Powhatan Uprising or The Great Assault. By definition, the incident was a massacre, but, using the same standard, so were many of the attacks by the English. The events of that March day were brutal, but they were neither the first, nor the last, horrific act perpetrated by both sides.

What should this event be called? For centuries, American textbooks called it the Indian or Jamestown “Massacre.” Recently, recognizing the complexities of the conflicts between the English and Powhatans, it has been preferable to call it the Powhatan Uprising or The Great Assault. By definition, the incident was a massacre, but, using the same standard, so were many of the attacks by the English. The events of that March day were brutal, but they were neither the first, nor the last, horrific act perpetrated by both sides.

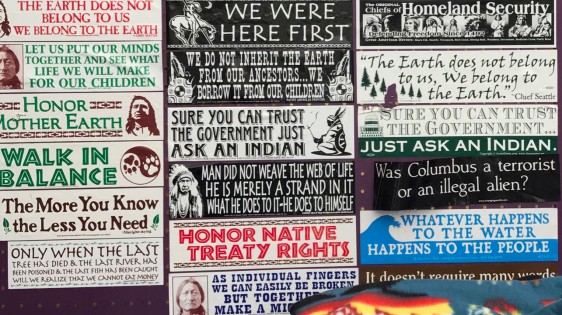

What story did the Powhatans tell about this time? Searching for the authentic 17th century Powhatan voice is difficult. There are voids; silences. Some of the tribes no longer exist–killed off by war and disease or absorbed as they were moved off their lands. Native Tribes were forced into submission and their tribal stories and traditions were suppressed, if not forbidden. By the 1800s, their Algonquin language was considered “dead” and most of their lands had been ceded to the English/ Americans.

What story did the Powhatans tell about this time? Searching for the authentic 17th century Powhatan voice is difficult. There are voids; silences. Some of the tribes no longer exist–killed off by war and disease or absorbed as they were moved off their lands. Native Tribes were forced into submission and their tribal stories and traditions were suppressed, if not forbidden. By the 1800s, their Algonquin language was considered “dead” and most of their lands had been ceded to the English/ Americans. There have been other attempts to explain the timing of the attack (phases of the moon, the English New Year, etc), but it does not appear there was a symbolic choice of dates. Helen Roundtree suggests that the Powhatans may actually have hoped to carry out the attack the prior year. It does make sense, though, that it would be carried out in the native season of cattapeuk (early spring) after the warriors had returned from their winter hunts where they could have laid plans out of earshot of English spies, and while their women and children were away fishing and foraging, out of the reach of the revengeful English.

There have been other attempts to explain the timing of the attack (phases of the moon, the English New Year, etc), but it does not appear there was a symbolic choice of dates. Helen Roundtree suggests that the Powhatans may actually have hoped to carry out the attack the prior year. It does make sense, though, that it would be carried out in the native season of cattapeuk (early spring) after the warriors had returned from their winter hunts where they could have laid plans out of earshot of English spies, and while their women and children were away fishing and foraging, out of the reach of the revengeful English.  Were the Powhatans and English really engaged in a war? Sometimes history books read more like there were just isolated and random attacks. Today scholars now divide this early period of colonial conflict into the First (1609-1614), Second (1622-1632), and Third Anglo-Powhatan Wars (1644-1646) with periods of truce and relative peace in between. There was no formal declaration of war, but at each point there were egregious acts which “quickly escalated into a bitter, vengeful ‘holy war’ for political hegemony and territorial control that neither side could afford to lose.” Each side became more determined to eliminate the other.

Were the Powhatans and English really engaged in a war? Sometimes history books read more like there were just isolated and random attacks. Today scholars now divide this early period of colonial conflict into the First (1609-1614), Second (1622-1632), and Third Anglo-Powhatan Wars (1644-1646) with periods of truce and relative peace in between. There was no formal declaration of war, but at each point there were egregious acts which “quickly escalated into a bitter, vengeful ‘holy war’ for political hegemony and territorial control that neither side could afford to lose.” Each side became more determined to eliminate the other.

It is sadly ironic that the first Native People the English encountered have been some of the last to receive tribal recognition. With much effort, Virginia now recognizes the following tribes: Cheroenhaka (Nottaway); Chickahominy; Eastern Chickahominy; Mattaponi; Monacan; Nansemond; Nottoway; Pamunkey; Patawomeck; Rappahannock; and Upper Mattaponi. In 2016, the Pamunkey tribe (to which Powhatan and Pocahontas belonged) became the first Virginia tribe to receive federal recognition. In 2018, the federal government also granted federal recognition to the Chickahominy; Eastern Chickahominy; Upper Mattaponi; Rappahannock; Nansemond; and Monacan tribes.

It is sadly ironic that the first Native People the English encountered have been some of the last to receive tribal recognition. With much effort, Virginia now recognizes the following tribes: Cheroenhaka (Nottaway); Chickahominy; Eastern Chickahominy; Mattaponi; Monacan; Nansemond; Nottoway; Pamunkey; Patawomeck; Rappahannock; and Upper Mattaponi. In 2016, the Pamunkey tribe (to which Powhatan and Pocahontas belonged) became the first Virginia tribe to receive federal recognition. In 2018, the federal government also granted federal recognition to the Chickahominy; Eastern Chickahominy; Upper Mattaponi; Rappahannock; Nansemond; and Monacan tribes. Attending the recent Nansemond Firebird Festival, I was reminded that the native nations that live amongst us are our closest 21st century neighbors. Can we finally learn respect and acceptance from our troubled shared history? Hopefully.

Attending the recent Nansemond Firebird Festival, I was reminded that the native nations that live amongst us are our closest 21st century neighbors. Can we finally learn respect and acceptance from our troubled shared history? Hopefully.

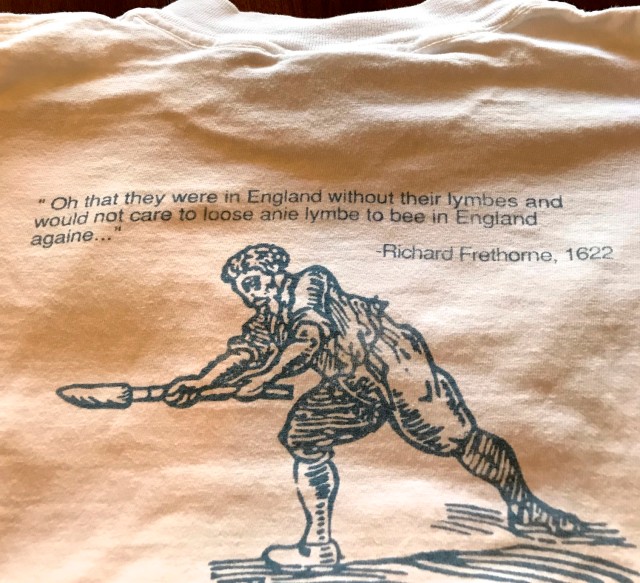

Indentureships were usually pre-arranged through a contract with set terms signed before the voyage between the potential servant and the ship’s captain or a merchant paying for the voyage. Usual terms were for 4-5 years, but it could be more for younger servants. Those contracts would then be sold to the planters when the ship arrived. Persons who arrived without a prior contract, but who wanted to be in service, might find their terms longer or less desirable, as their services were sold in the “custom of the country.” I will focus on Virginia in this post, but indentured servants were also heading to the West Indies, Barbados, Ireland, and other British colonies.

Indentureships were usually pre-arranged through a contract with set terms signed before the voyage between the potential servant and the ship’s captain or a merchant paying for the voyage. Usual terms were for 4-5 years, but it could be more for younger servants. Those contracts would then be sold to the planters when the ship arrived. Persons who arrived without a prior contract, but who wanted to be in service, might find their terms longer or less desirable, as their services were sold in the “custom of the country.” I will focus on Virginia in this post, but indentured servants were also heading to the West Indies, Barbados, Ireland, and other British colonies.

What seemed to make the difference between those who survived and those who did not? Among indentured servants, older ones with some education, skills, and/or connections fared better. Outcomes were surely affected as well by individual personalities, self- advocacy skills, and work ethics. Potential servants might have been able to choose a broad destination (Virginia v. West Indies),and those who sought advice and input in advance may have fared better.

What seemed to make the difference between those who survived and those who did not? Among indentured servants, older ones with some education, skills, and/or connections fared better. Outcomes were surely affected as well by individual personalities, self- advocacy skills, and work ethics. Potential servants might have been able to choose a broad destination (Virginia v. West Indies),and those who sought advice and input in advance may have fared better.

with his former indentured servant, Adam Thorowgood. Once again, Adam had been fortunate.

with his former indentured servant, Adam Thorowgood. Once again, Adam had been fortunate.

However, by the following year’s proclamation, President Kennedy recognized that there was more than one claim to being first and that the Pilgrims’ feast with the Wampanoag tribe in 1621 did not establish a yearly precedent. (2)

However, by the following year’s proclamation, President Kennedy recognized that there was more than one claim to being first and that the Pilgrims’ feast with the Wampanoag tribe in 1621 did not establish a yearly precedent. (2)

Long before Europeans arrived, they had their own harvest feasts, expressing thanks to the Great One and eating wild turkey, corn, squash, and other foods that are part of today’s Thanksgiving traditions. While some tribes see a connection between Thanksgiving and their ancient beliefs and practices, others have used that time to protest the overall treatment of the indigenous people in this country. (8)

Long before Europeans arrived, they had their own harvest feasts, expressing thanks to the Great One and eating wild turkey, corn, squash, and other foods that are part of today’s Thanksgiving traditions. While some tribes see a connection between Thanksgiving and their ancient beliefs and practices, others have used that time to protest the overall treatment of the indigenous people in this country. (8)

Although the Charles made about four known journeys to Jamestown, it was not one of the regulars.

Although the Charles made about four known journeys to Jamestown, it was not one of the regulars.