Let us of this Nation pray, pray that God would return the Head to the Body, the King to the Parliament; that He will heal our breaches, compose our differences, and hasten the restoration of a safe and well grounded Peace… [1]

So ended the lengthy address to the English House of Commons on December 25, 1644, by the Puritan Rev. Thomas Thorowgood, one of Adam Thorowgood’s older brothers. It was a notable “Christmas,” for in the weeks before, the Puritan-led Parliament had banned the celebration of this tradition-rich holiday, declaring that it should be noted only by the Wednesday monthly fast that happened to fall on the 25th.

It was in these circumstances that Rev. Thorowgood, one of the appointed members of the Westminster Assembly of Divines, “being summoned to the service…found…my lot was cast upon that very day, which the providence of heaven had designed to fall on Christmas Day….The election of a Theme and the manner of handling it was in my power, and by Divine guidance I chose Moderation.” [2] His chosen text was from Philippians 4:5:

Let your moderation be known unto all men; the Lord is at hand.

The Turning Tide in the English Civil War

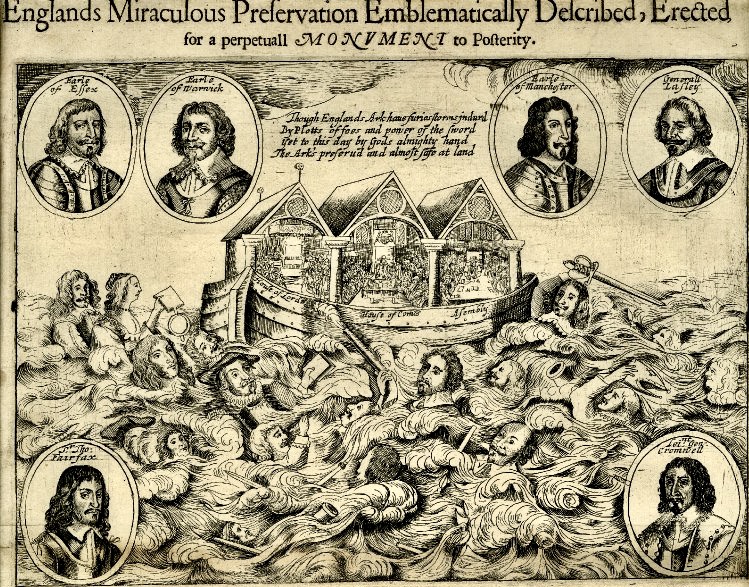

For two years, England had been in the throes of a Civil War, torn between royalists who supported the rigid King Charles I and reformers who sought to increase the powers of Parliament, with the sides fractured on matters of religion. Most English still hoped there could be a reconciliation with improved and more responsive governance, although a few were already calling for the end to the monarchy. Both sides vied for the support of Scotland and its troops that vacillated according to the support they perceived for maintaining their Presbyterian Scottish Kirk in Scotland and extending it to become the state religion of England. However, despite Parliament’s acceptance of “The Covenant” in 1643 which required all English and Scottish citizens to subscribe to the Scottish version of the church, Anglican royalists, English Puritans, and the less-sectarian Independents resisted widespread acceptance of Presbyterian governance of their churches. [3]

The Parliamentarian forces had achieved a major victory against the royalists and their Scottish allies the prior summer at Marston Gap and were now in control of Northern and Eastern England. The war had turned in their favor. Lt. General Oliver Cromwell had brilliantly routed royalist forces with his specially recruited calvary that he had filled with “godly, honest men” who were committed to fight for the “preservation of the true religion, the laws, liberty, and peace of the Kingdom.” Cromwell forbade engaging in customary troop behavior, such as plundering, getting drunk, whoring, and swearing. Many of Cromwell’s recruits came from his home region, the Puritan-leaning East Anglia, where Thomas Thorowgood was a minister. [4]

Inspired by Cromwell’s successes, Parliament was preparing at the end of 1644 to reorganize its army into the national New Model Army which would emphasize efficiency and merit. In an attempt to make this new army less political, those serving in both the military and Parliament were forced to choose between those positions through the Self-Denying Ordinance. However, the army ended up with greater representation of Independents like Cromwell than fervent Presbyterians which ultimately resulted in its own conflicts. While the New Model Army’s focus was to win battles, there was a general religious orientation, and they were issued a special Soldiers Catechism. It was also the first time there was a national uniform created for the troops who became called “redcoats.” [5]

Inspired by Cromwell’s successes, Parliament was preparing at the end of 1644 to reorganize its army into the national New Model Army which would emphasize efficiency and merit. In an attempt to make this new army less political, those serving in both the military and Parliament were forced to choose between those positions through the Self-Denying Ordinance. However, the army ended up with greater representation of Independents like Cromwell than fervent Presbyterians which ultimately resulted in its own conflicts. While the New Model Army’s focus was to win battles, there was a general religious orientation, and they were issued a special Soldiers Catechism. It was also the first time there was a national uniform created for the troops who became called “redcoats.” [5]

In discussing the second part of his text, “the Lord is at hand,” Rev. Thorowgood saw similarities between prophesied destructions that would come upon the world prior to Christ’s return and what had occurred in England in a few short years. He wished that

the Kingdoms may yet be happy in a safe and well-grounded Peace; and it is high time to hasten it, the whole Land almost is already laid waste by the Sword, which, if not speedily sheathed, is bringing upon us a worse evil unavoidably, a Famine; for they that be slain with the sword are better then they that be slain with hunger…but let not the fear of Sword or Famine scare you into any other Peace than that which is the Peace of God made in Christ, joined with truth, else a greater mischief will fall upon the Nation than war or hunger; Not a famine of bread or a thirst for water, but of hearing the word of God (Amos 8:11)…..

O England: never since thou wert a Nation didst thou see thyself so miserably torn and rent with such uncivil, unnatural, and bloody distractions: If it had been said to any of thy people, four or five years since, that they should do such things, as are now done in the midst of thee, they would have replied with indignation….Wretched things are done by men, Christian men, Englishmen against Englishmen, professing the same Religion, protesting the same Cause and End of their quarrel: O that thou couldst yet discern those formidable clouds of blood in their scattering: but alas, they threaten worser evils, even to make thee a full sea of blood within as thou art without surrounded by water….But let all those be ashamed and astonished, prophets and people, that have not helped to quench, but kindle this fire: This is indeed a lamentation. [6]

Thomas Thorowgood and the Westminster Assembly of Divines

Who was this minister who should boldly plead for peace before Parliament during this time of war? Thomas Thorowgood was born in 1588 in Grimston, Norfolk, where his father, William Thorowgood, was the Rector. He was educated at Queen’s College at Cambridge and himself became a rector at Massingham, Norfolk in 1621. After his father passed in 1625, he became the rector at Grimston. While the presiding bishops of Norwich in those years were Anglican and mostly anti-Puritan, the citizenry of Norfolk developed strong Puritan leanings, influenced by the earlier influx of Protestant refugees who fled there from religious persecution in France and the Low Countries. Thomas Thorowgood became known as a strong Puritan and was respected as a cleric and theologian. While Thomas never traveled to Virginia to visit his younger brother Adam Thorowgood, his wife’s brother Edward Windham (Wyndham) became one of Adam’s headrights and prospered in Lower Norfolk County, Virginia, alongside Adam. Thomas later became interested in the origins of North American indigenous tribes and postulated that they were of the lost tribes of Israel. This and his communication with New England Puritan leaders will be discussed in a future post. [7]

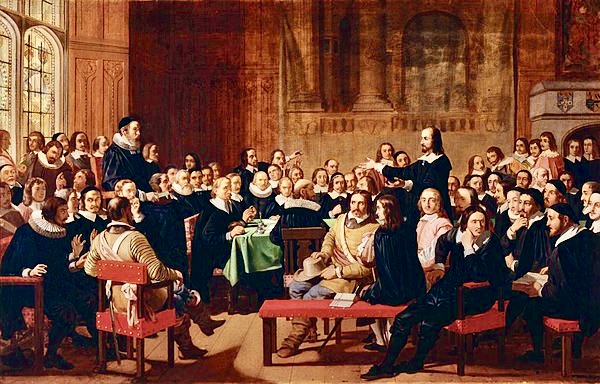

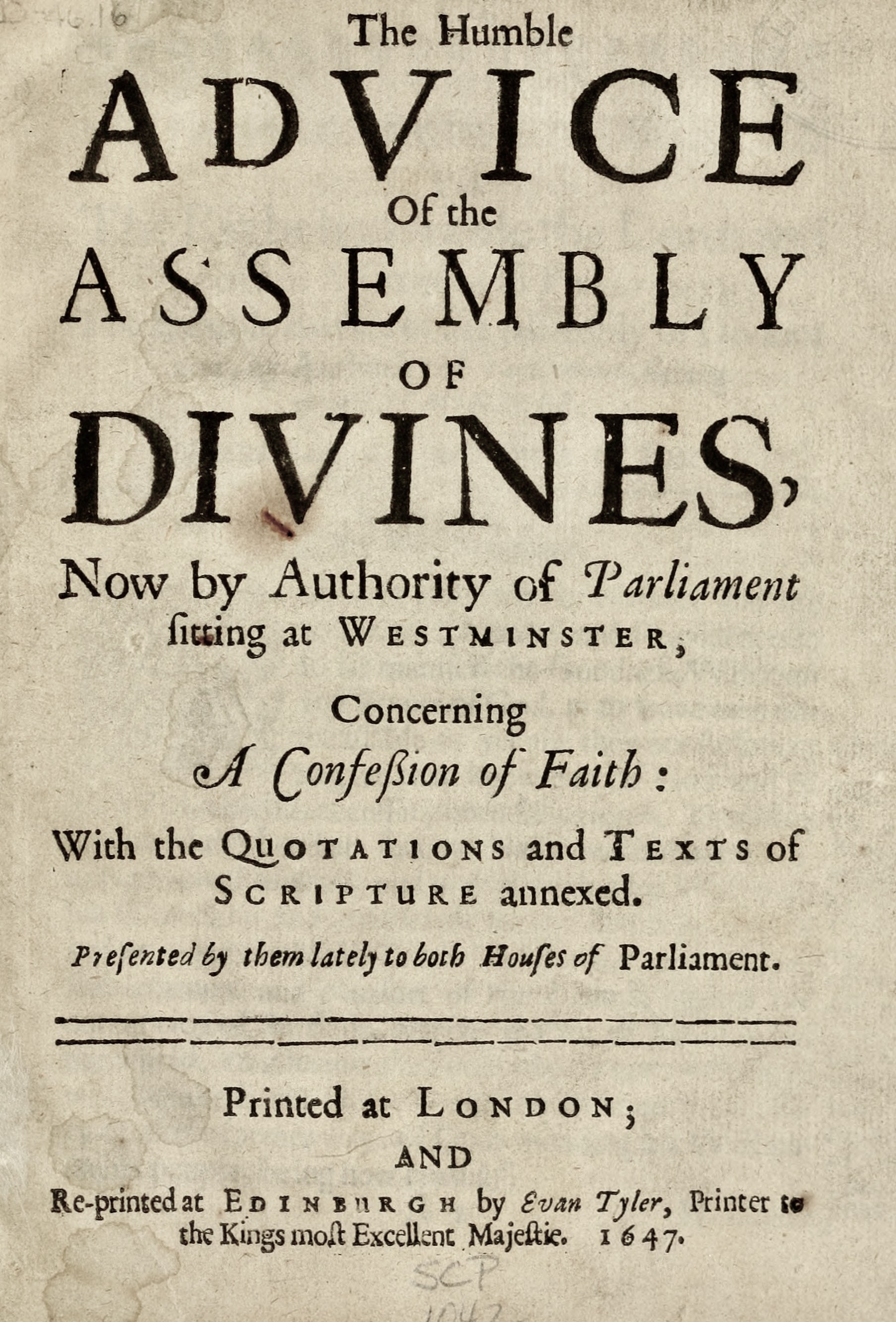

In April 1642, Parliament authorized the calling of an Anglo-Scottish synod of “divines” to revise the prayer book (rejecting the Anglican Common Book of Prayer) and decide matters regarding acceptable church liturgy, practices, and governance. Invited were 121 ordained ministers, 10 peers, 20 MPs as lay assessors, and 8 Scots (5 clerics and 3 laymen). The Assembly opened on July 1, 1643 at Westminster and continued until 1653. No Anglican ministers were appointed. Thomas Thorowgood was one of two selected to represent Norfolk, and he served from 1643 until 1649. In 1646, the Assembly published a New Confession of Faith based on Calvinistic doctrine and prescribed a Presbyterian form of church governance. Although the church in Scotland continued to employ the Westminster Assembly’s standards, they were revoked in England in 1660 when the Anglican Church was reinstated with the restoration of Charles II. [8]

In April 1642, Parliament authorized the calling of an Anglo-Scottish synod of “divines” to revise the prayer book (rejecting the Anglican Common Book of Prayer) and decide matters regarding acceptable church liturgy, practices, and governance. Invited were 121 ordained ministers, 10 peers, 20 MPs as lay assessors, and 8 Scots (5 clerics and 3 laymen). The Assembly opened on July 1, 1643 at Westminster and continued until 1653. No Anglican ministers were appointed. Thomas Thorowgood was one of two selected to represent Norfolk, and he served from 1643 until 1649. In 1646, the Assembly published a New Confession of Faith based on Calvinistic doctrine and prescribed a Presbyterian form of church governance. Although the church in Scotland continued to employ the Westminster Assembly’s standards, they were revoked in England in 1660 when the Anglican Church was reinstated with the restoration of Charles II. [8]

Moderation, A Shining Grace

Rev. Thorowgood recommended Moderation as a desired quality as it would restrain excesses and extremes and resist revenge in his tumultuous time. While I do not agree with the assertion that revenge is a feminine passion (a reflection of attitudes of his time) or his view on religious toleration, moderation is a virtue we still struggle to possess today. Rather than taking offense at Thorowgood’s message, his address so pleased Parliament that they requested he publish it. Thus it was preserved for us today.

(Moderation is) a grace shining outwardly; it is visible, and illustrious, known unto men; it hath influence into all other virtues; it qualifies and tempers them; it is as salt that makes other things savory; they relish not so well without the salt of Moderation; it is the grain that evens the scale; it curbs excesses, supplies defects, and is every way helpful; a well-doing grace, so good, that it doth ill to none… even nature did ever account desire of revenge a feminine and cowardly passion…..This Moderation is of such vast and comprehensive extent that it checks all overflowings of heart, tongue, gesture, apparel, diet; yea it hath influence upon all our doings and sufferings: [9]

While striving for this virtue can bring balance and peace in one’s life, Rev. Thorowgood also recognized that the stresses of life can sometimes obscure such feelings. He saw patience as a needed companion to moderation. Indeed, it is easy for all of us “to abound in complaining” when things go wrong.

Though we have had twenty years of felicity, if one day of sorrow come, all the former calmness is forgotten, clouds of indignation gather, and break out into streams of impatience; nay, if one tooth do but ache, that Center or point of pain darkens all the Sphere and circumference of Gods mercies; It were easy to abound in complaining. [10]

Moderation was seen as of value to both individuals and nations. However, Rev. Thorowgood did not see moderation as constraining zeal in either religious devotion or military endeavors. He also did not believe that moderation demanded tolerance of contrary beliefs or opinions:

…new opinions suffered will devour the old, and the toleration of every Religion will destroy all Religion: and …leave no Religion at all….This liberty is inconsistent with civil tranquillity; the bleeding condition of our own Nation at present is a living, almost a dying witness of this;….This may be current doctrine among the Turks:..As a Garden is beautified with variety of flowers, so his Empire would be adorned with diversities of religion: let such toleration find allowance in the Turks’ Paradise; it shall never, I trust, be planted in the Paradise of God (England). [11]

A Puritan Non-Christmas

In prior days, England had been known to make quite merry during the Twelve Days of Christmas which ended with gift giving on January 6, the Day of Epiphany. While Christmas Day would have been reserved for church services, the remaining days were filled with parties, dances, plays, bonfires, feasting, and drinking. Homes might be decorated with rosemary, holly, and garlands, and many enjoyed the often bawdy entertainment and partying under the “Lord of Misrule.” Such merriment continued under the Protestant King Henry VIII, Elizabeth I, and even King James I. However, how to respond to Christmas was a matter of debate early in the English Civil War. Thomas Fuller in a sermon in 1642 acknowledged that the youth were “so addicted to their toys and Christmas sports that they will not be weaned from them,” but encouraged the adults to instead choose a holy fast over the traditional feast. [12]

This approach to Christmas was not well received by the populace. Apprentices who lost their day off rioted in London against shop owners who complied with keeping their shops open in non-observance of the holiday. Some homes and even a few Puritan churches continued to decorate for Christmas. The declared Puritan days of fasts and thanksgivings never captured the hearts and imaginations of the people or produced a communal feeling like the religious festivals had. The denial of such entertainments only led to increased noncompliance and resentment against Puritan leaders. [13]

This approach to Christmas was not well received by the populace. Apprentices who lost their day off rioted in London against shop owners who complied with keeping their shops open in non-observance of the holiday. Some homes and even a few Puritan churches continued to decorate for Christmas. The declared Puritan days of fasts and thanksgivings never captured the hearts and imaginations of the people or produced a communal feeling like the religious festivals had. The denial of such entertainments only led to increased noncompliance and resentment against Puritan leaders. [13]

In justification of Parliament’s approach to Christmas, Rev. Thorowgood explained in his sermon in 1644 that:

this day (Christmas), and those next it, have been heretofore the only merry season of the year, and the Devil hath been served better on those Twelve days than on all the twelve months beside; and our Master Christ hath most unchristianly by many been dishonored, even in those days said to be devoted to his glory:…Great cause therefore had your Ordinance to command this day to be kept with more solemn humiliation, because it may call to remembrance our sins and the sins of our fore-fathers who have turned this feast, pretending the memory of Christ, into an extreme forgetfulness of him, by giving liberty to cranial and sensual delights, being contrary to the life which Christ himself led here upon earth….[14]

Celebrating with Charity

Noting that the choice of the date and manner of the Christmas celebration had more to do with the pagan solstice celebrations than Christ’s actual birth date which Rev. Thorowgood and others had concluded was likely in the spring, Thorowgood expressed willingness to accept another date and manner of celebrating the birth:

Noting that the choice of the date and manner of the Christmas celebration had more to do with the pagan solstice celebrations than Christ’s actual birth date which Rev. Thorowgood and others had concluded was likely in the spring, Thorowgood expressed willingness to accept another date and manner of celebrating the birth:

I wish …that those heathenish, mad, and riotous usages…might be quite abandoned for ever; but let the neighborhood and charity of those times at least in some time of the year be continued; sure I am that some who had withered hands all the year …did at that season stretch them out to the poor…. If the serious disquisition of Historians and Mathematicians shall calculate and design the month & the day, I shall not vote against the Christian celebration thereof, but as at Berne when the Gospel was first reintroduced, they set their prisoners at liberty and proclaimed freedom; and we [should] observe a Day in memory of our Deliverance. [15]

These thoughts of Rev. Thorowgood remind me of Dickens’ imagined response centuries later in The Christmas Carol which came to define many of today’s Christmas traditions. In response to the remarks of Ebenezer Scrooge, his nephew Fred replied:

I have always thought of Christmas time… as a good time; a kind, forgiving, charitable, pleasant time… the only time… when men and women seem by one consent to open their shut-up hearts freely, and to think of people below them as if they really were fellow-passengers…. [16]

This holiday season may we, as Rev. Thorowgood encouraged, employ the attributes of moderation in our lives and be among those who stretch out our hands to others in our chosen holiday celebrations.

The author modernized the spelling and some punctuation of Thomas Thorowgood’s address for ease in reading.

Footnotes:

[1] Thorowgood, Thomas, Moderation justified, and the Lords being at hand emproved,: in a sermon at Westminster before the Honorable House of Commons assembled in Parliament: preached at the late solemne fast, December 25. 1644. By Thomas Thorowgood B. of D. Rector of Grimston in the county of Norfolke: one of the Assembly of Divines. Published by order from that House (London: Christopher Meredith at the Crane in St. Paul’s Churchyard, 1645), 33. Accessed through Early English Books Online at Moderation Justified on November 1, 2022.

[2] Thorowgood, preface, 1.

[3] Woolrych, Austin, Britain in Revolution 1625-1660 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), 271-272.

[4] Ackroyd, Peter, Rebellion: The History of England from James I to the Glorious Revolution (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2014), 270-274. Hibbert, Christopher, Charles I: A Life of Religion, War and Treason (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007), 202-203. Martins, Susanna Wade, A History of Norfolk (Chichester, West Sussex: Phillimore & Co., Ltd., 1997), 55.

[5] Woolrych, 306-307. Ackroyd, 274-275.

[6] Thorowgood, 19, 23.

[7] Hall, Stephanie, “Our Grimston Rectors,” accessed online on November 5, 2022 at our-rectors-revised, 2021. Martins, 53. McCartney, Martha W., Jamestown People to 1800 (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company, 2012), 452.

[8] Woolrych, 220-221, 271. “List of Members of the Westminster Assembly,” Wikipedia. accessed online on November 15, 2022 at list of members, 2022.

[9] Thorowgood, 5-7.

[10] Ibid., 29.

[11] Ibid., 12.

[12] Durston, Chris, “Lords of Misrule: The Puritan War on Christmas 1642-1660,” History Today (December 1985). Accessed online on November 9, 2022 at misterdann.com.

[13] Underdown, David, Revel, Riot, and Revolution: Popular Politics and Culture in England 1603-1660 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985), 256-257, 261.

[14] Thorowgood, 25.

[15] Thorowgood, 18.

[16] Dickens, Charles, A Christmas Carol (New York: Fall River Press, 2009), 25.