As the early English emigrants decided which possessions to pack for their life in Virginia, they may not have considered the traditions and expectations they would bring with them. Most coming to Virginia were not wanting to break with their Mother Country, but rather to expand their own opportunities in an undeveloped land under the same governing rules. Seventeenth-century England had a well established court system and extensive English Common Law precedents. But how would these fit with the new circumstances of colonial life?

Remarkably, the records of the Lower Norfolk County Court have survived for 384 years despite the area’s humid climate, poor storage conditions, wars, and fires. Many of Virginia’s county court records that had survived to the 1860s were sent to its capital during the Civil War for “safe keeping,” but were unfortunately lost in the burning of Richmond. However, according to tradition, “a level-headed clerk” of Princess Anne County (as the county was then called) “loaded his precious record books into a covered wagon and drove off into the Dismal Swamp, not to reappear until the fighting was safely over.” [1] Wherever those records were kept, they fortunately survived along with those of a few other Virginia counties. As the Lower Norfolk Court began meeting in 1637, its records are among the oldest of the Virginia courts and provide an invaluable window into the dilemmas of early colonial life.

Lower Norfolk County’s First Court Case

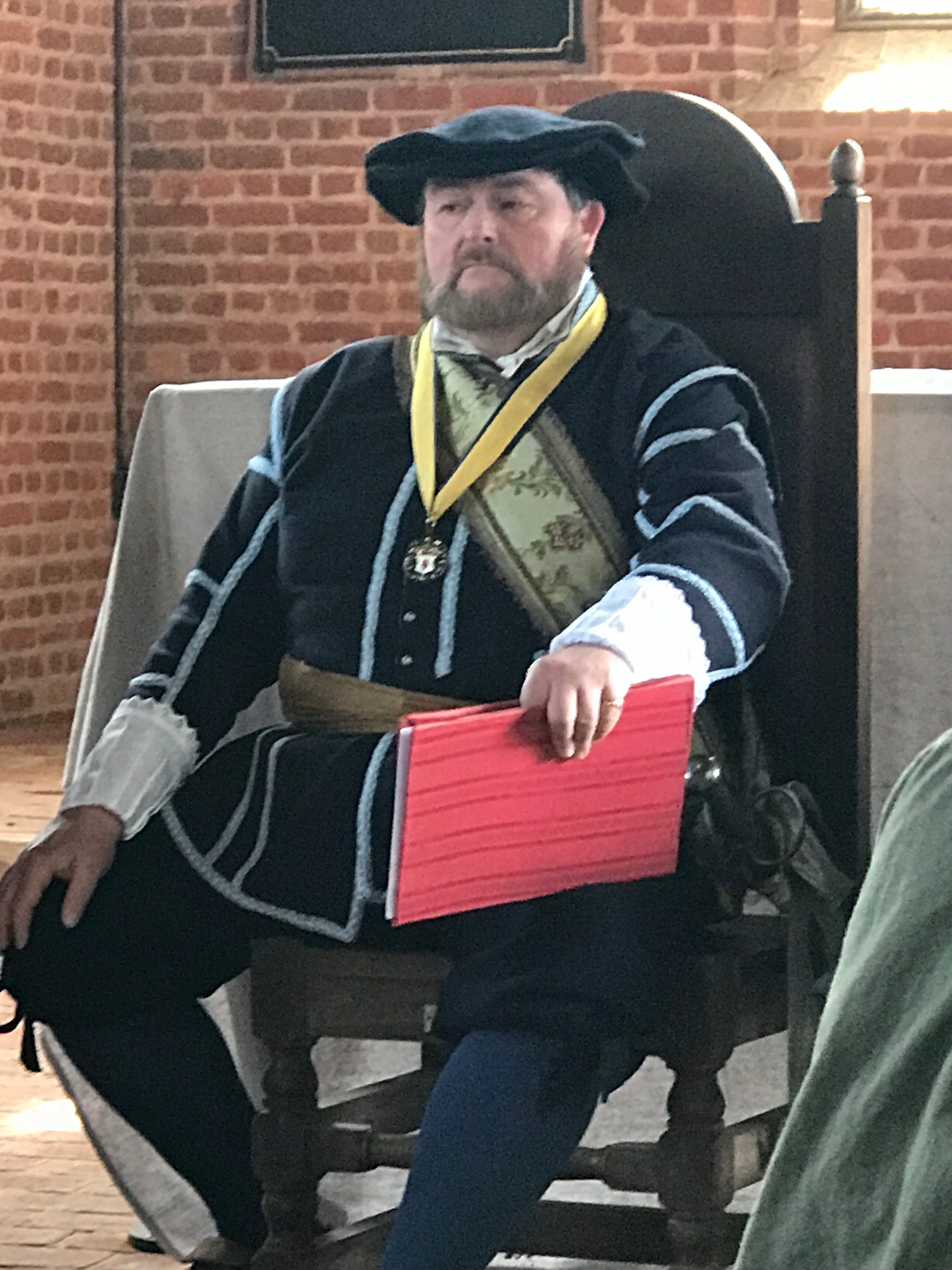

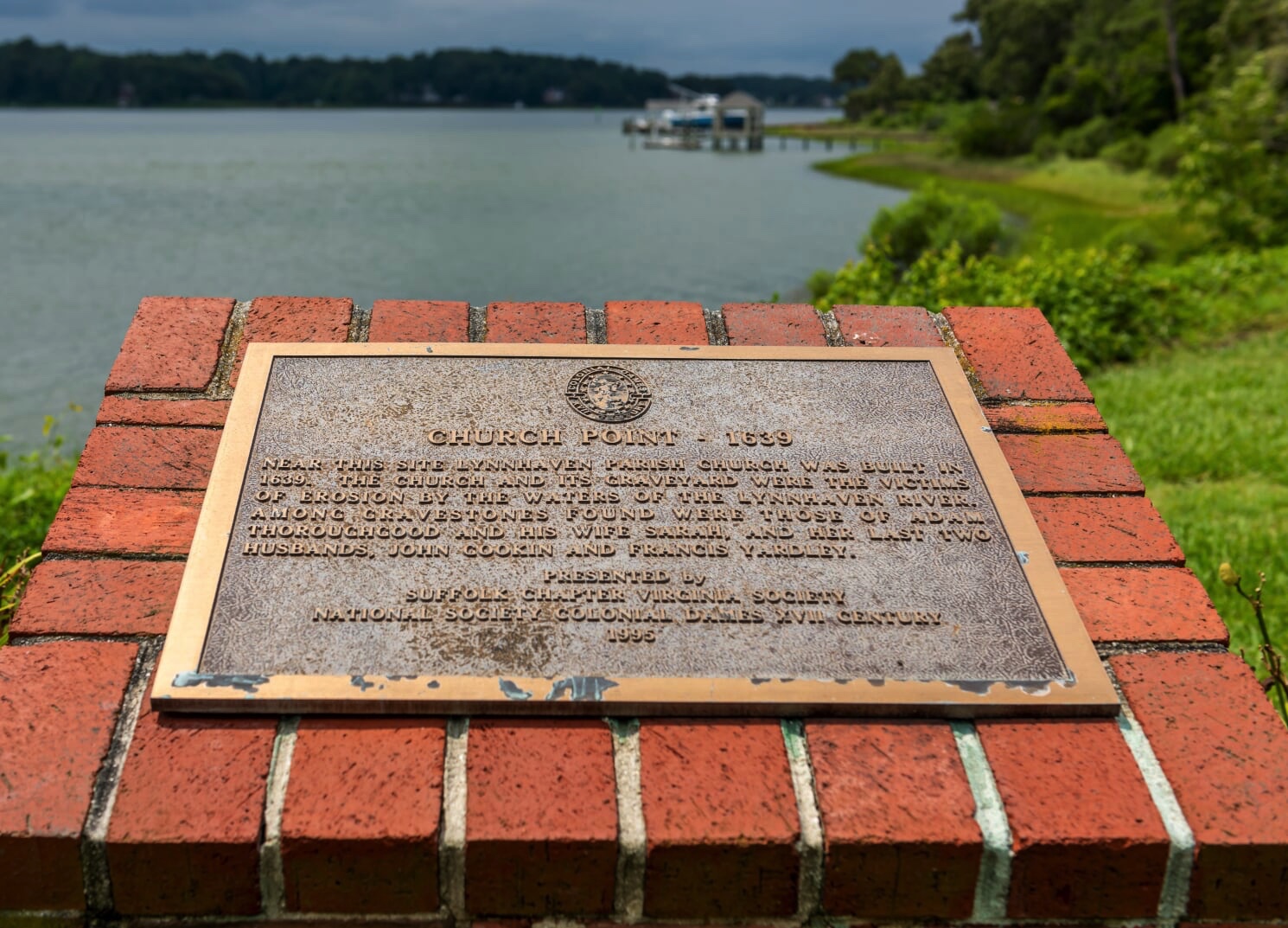

“At court holden in the Lower County of New Norfolke the 15th of Mae, 1637,” Capt. Adam Thorowgood, Esq. presided over the first of its courts in his home with the following appointed justices: Capt. John Sibsey, Edward Windham, William Julian, Francis Mason, and Robert Came. [2] This was not Adam’s first time sitting on a court, although neither he nor any of the other justices had had any legal training. On March 20, 1628, Adam Thorowgood had first been appointed a commissioner of Elizabeth City’s monthly court by Gov. Francis West and was authorized to hold court in his home, as was customary in those early years. [3] A justice was a lifetime appointment, but one for which there was no payment. Adam served until his death in 1640, presiding for 12 of Lower Norfolk’s first 13 sessions.

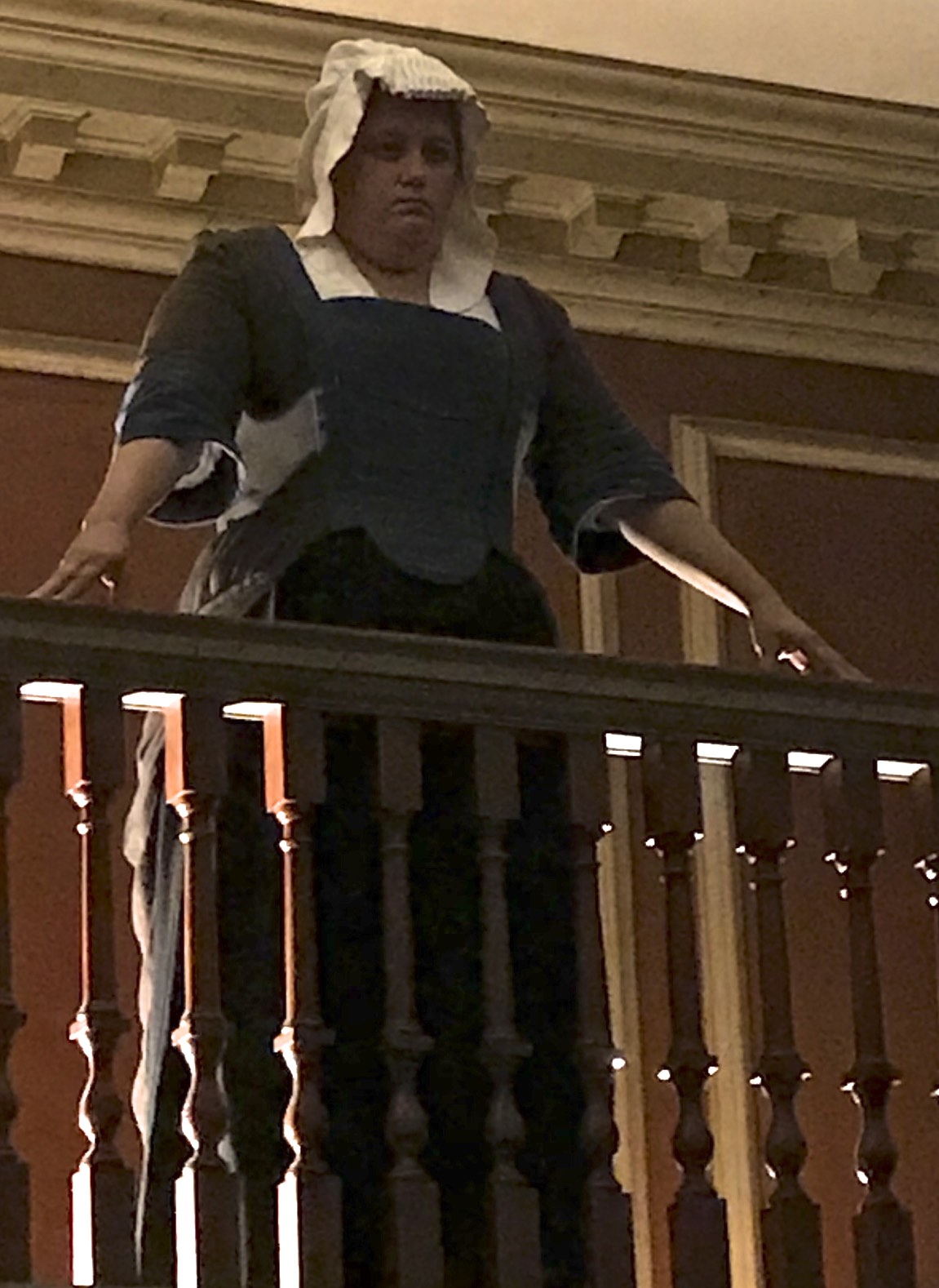

The first case of the first court was actually brought by Adam Thorowgood against a woman, Ann Fowler. Thorowgood’s servants had found and marked a lost cask by the seaside which William Fowler later came upon and took to his house. It was not the taking of the cask which was at issue, but Mistress Fowler’s responses when Adam’s servants came to claim it. Mistress Fowler was brought to court because, when told the cask would be returned to Capt. Thorowgood, she declared, “Let Capt. Thorowgood Kiss my arse.” She also called the agent of Thorowgood, Thomas Keeling, a “Jacknape, Newgate rogue, and brigand” and threatened if he did not leave, “she would break his head.” When this was confirmed by other witnesses, the court found that Anne Fowler did “in a shameful, uncomely and irreverent manner…with aggravation of many unusual terms” disrespect Adam Thorowgood and in a “shameful and reproachful manner…with abusive names and promiscuous speeches” defame Thomas Keeling. She was sentenced to 20 stripes on her bare shoulders and required to ask forgiveness of Adam Thorowgood and Thomas Keeling at the court that day and at Church on Sunday, both of which were held at the Thorowgood house. [4]

The first case of the first court was actually brought by Adam Thorowgood against a woman, Ann Fowler. Thorowgood’s servants had found and marked a lost cask by the seaside which William Fowler later came upon and took to his house. It was not the taking of the cask which was at issue, but Mistress Fowler’s responses when Adam’s servants came to claim it. Mistress Fowler was brought to court because, when told the cask would be returned to Capt. Thorowgood, she declared, “Let Capt. Thorowgood Kiss my arse.” She also called the agent of Thorowgood, Thomas Keeling, a “Jacknape, Newgate rogue, and brigand” and threatened if he did not leave, “she would break his head.” When this was confirmed by other witnesses, the court found that Anne Fowler did “in a shameful, uncomely and irreverent manner…with aggravation of many unusual terms” disrespect Adam Thorowgood and in a “shameful and reproachful manner…with abusive names and promiscuous speeches” defame Thomas Keeling. She was sentenced to 20 stripes on her bare shoulders and required to ask forgiveness of Adam Thorowgood and Thomas Keeling at the court that day and at Church on Sunday, both of which were held at the Thorowgood house. [4]

What kind of a court was this that could demand both physical punishment and contrition in church? What basis did they have for their decisions? How could justice be done with such conflicts of interest?

Establishing County Courts in Virginia

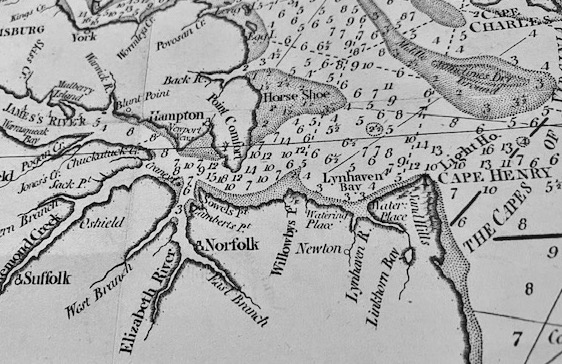

In the transformational year 1619 when Virginia became the first English colony with representational government, it was proclaimed that colonists would govern “by those free laws which his Majesty’s subjects live under in England.” As it was too cumbersome for all matters to be resolved by the General Court, comprised of the Governor and his Councillors in Jamestown, local courts started to be set up in 1624 in outlying areas including Accomack, Charles City, and Elizabeth City. However, it was not until 1634 that the Virginia General Assembly organized the expanding colony into eight shires or counties and gradually established local administration through the county courts. In 1636, New Norfolk was formed from Elizabeth City, and shortly thereafter, Lower Norfolk County was created. [5]

These county courts had a basic semblance to the local Courts of Quarter Sessions in England, but their responsibilities and jurisdictions differed. While Virginia’s General Court handled higher judicial matters, including felonies, serious crimes, and appeals from lower courts, the county courts acquired responsibility for routine governance and legal administration. County courts could not take “life or limb,” but they were granted many responsibilities assumed in England by separate administrative, admiralty, criminal, civil, chancery, and ecclesiastical courts without any special training of the justices. [6]

Justices were appointed by the Governor from recommendations by his Council or local authorities. Like Thorowgood, they would have been respected, landed gentlemen or wealthy merchants under the old English assumption that the wealthy and positioned would be the best rulers and judges. Such appointed individuals would often be involved with judicial, legislative, and executive functions simultaneously. In Elizabeth City, Adam Thorowgood was both an appointed justice and an elected Burgess. He was appointed to the Governor’s Council the same year he was appointed a Justice for Lower Norfolk County and, as such, would have helped pass and enforce laws as well as helped appoint other justices, decided felonious cases, and heard appeals from the lower courts. Of the other six justices that served during Thorowgood’s tenure, John Sibsey and Henry Seawell were Burgesses; Francis Mason and William Julian were established Ancient Planters; and Edward Windham, one of Adam’s headrights, was the brother of Adam’s sister-in-law (Ann Wyndham Thorowgood). Little is known of Robert Came who only served that first year. Between 1634-1676, Warren Billings found the average land holding for 215 Council members and justices from Lower Norfolk, Lancaster, Northumberland, and York counties was over 1,000 acres, more than double the average holdings of other Virginia planters. [7]

Justices were appointed by the Governor from recommendations by his Council or local authorities. Like Thorowgood, they would have been respected, landed gentlemen or wealthy merchants under the old English assumption that the wealthy and positioned would be the best rulers and judges. Such appointed individuals would often be involved with judicial, legislative, and executive functions simultaneously. In Elizabeth City, Adam Thorowgood was both an appointed justice and an elected Burgess. He was appointed to the Governor’s Council the same year he was appointed a Justice for Lower Norfolk County and, as such, would have helped pass and enforce laws as well as helped appoint other justices, decided felonious cases, and heard appeals from the lower courts. Of the other six justices that served during Thorowgood’s tenure, John Sibsey and Henry Seawell were Burgesses; Francis Mason and William Julian were established Ancient Planters; and Edward Windham, one of Adam’s headrights, was the brother of Adam’s sister-in-law (Ann Wyndham Thorowgood). Little is known of Robert Came who only served that first year. Between 1634-1676, Warren Billings found the average land holding for 215 Council members and justices from Lower Norfolk, Lancaster, Northumberland, and York counties was over 1,000 acres, more than double the average holdings of other Virginia planters. [7]

Many of the cases left to county courts fell within the tradition of English common law with the expectation that the untrained justices would govern “by laws resembling those of England as closely as circumstances would permit.” The overriding principle to guide them was seeking “perfect justice and equity of the case.” [8] It was hoped that these teams of justices would use their collective wisdom, governmental experience, and Christian ethics to make reasonable decisions and do right by their citizens.

Many of the cases left to county courts fell within the tradition of English common law with the expectation that the untrained justices would govern “by laws resembling those of England as closely as circumstances would permit.” The overriding principle to guide them was seeking “perfect justice and equity of the case.” [8] It was hoped that these teams of justices would use their collective wisdom, governmental experience, and Christian ethics to make reasonable decisions and do right by their citizens.

English trial procedures were employed, and evidence and witnesses could be presented by both sides. Jury trials were allowed, but the first known one in Lower Norfolk was not until March 1642 when hogs belonging to Capt. John Gookin, (the new husband of Adam Thorowgood’s widow Sarah) escaped their pen and damaged the corn field of their neighbor Richard Foster. As Gookin had installed sturdy fencing to try to keep his hogs in and Foster had none to keep animals out, the jury found for Mr. Gookin. Generally, though, plaintiffs prevailed. Adam Thorowgood, Henry Seawell, John Sibsey and William Julian all had cases before the court in the years when they were sitting. Most of them won their cases, although there were findings against William Julian for some owed debts. As with most institutions at the time, courts were the domain of men, although women were plaintiffs, defendants, and witnesses. How women, particularly Sarah Thorowgood Gookin Yeardley, interacted with the Lower Norfolk Court will be discussed in future posts.[9]

Property Crimes and Debt in Lower Norfolk

William E. Nelson, an English legal scholar, noted that, while each of the English colonies incorporated English common law, initially they did so differently according to their founding purposes. New Englanders were focused on establishing and protecting their desired religious-based society; Maryland sought to ensure protection for their Catholic religious minority; and Virginia, which had principally been founded for economic opportunity, emphasized the protection of property.[10] Thus, it is not surprising that much of the work of the early Virginia courts dealt with issues of debt and property acquisition.

During the first two years (1637-1639), the Lower Norfolk County Court had 110 cases. Of those, 20 involved administrative duties. Of the remaining 90 disputed civil and criminal cases, the majority (68%) involved a plaintiff seeking payment of a debt, generally in pounds of tobacco or occasionally, corn. The amounts owed varied from 72 to 2,000 lb. tobacco, but were mostly in the 300-700 lb. range. As several debtor names reappeared, it was evident that not all were profiting in the tobacco trade, and the greatest debts were owed to merchants. Although the justices generally ordered debts to be paid in 10 days, they did show some mercy and granted extensions, sometimes until the next harvest.

There was only one incident of reported theft when a servant of John Sibsey stole and bartered his master’s goods for which he received 30 stripes. However, there were 7 (8%) incidents of breach of contract. An indentured servant had his time extended for misinforming the court of his end date; one left the colony before finishing his indentureship; and another owed 7 days of work. When Henry Catlinge settled on land that belonged to Cornelius Lloyd and made improvements despite warnings, the court required Catlinge to leave, but Lloyd had to reimburse him for the improvements. [11]

Adam Thorowgood was particularly active in enforcing his agreements and property rights through the courts. When Daniel Tanner, a carpenter, did not finish buildings for the Thorowgoods, the work was given to another and Tanner was fined 3 barrels of corn. Adam’s goat keeper who beat the animals excessively was both fined and received 40 lashes himself. Christopher Burrows had to promise to return “a negro” to Adam Thorowgood if he did not pay within 10 days . It is not stated if this enslaved individual was being sold or lent out for a time. As noted in a prior post, Adam had purchased several enslaved individuals. Although no reason is stated in the record, Adam Thorowgood and Francis Land had come to an agreement that Land would not hire Cobb Howell without Adam’s permission. However, Francis Land and Cobb Howell had made plans to make 200 hogshead together. The other justices found in favor of Adam Thorowgood, so Francis Land appealed to the Jamestown General Court, even through Thorowgood was on that court, too. [12]

Slander, Disrespect, and Sexual Misconduct

Slander cases (11%) were scandalous and spectacular. While some of the complaints may seem petty by our modern standards, they were a serious matter in colonial courts. The first case referenced above was about more than Thorowgood’s bruised ego and clearly sent a message to county residents. This was a very new community that was just coming together, as everyone had arrived within the prior 3-4 years when land grants were given. It was the beginning of local administration for this county and, while some justices might have known each other previously in Elizabeth City, it was the first time they were working together as a unit. It was also an era when respect and deference were expected: children to parents, servant to master, subject to the King and his envoys. Yet, cases sometimes revealed underlying resentment and anger against their successful leaders. [13]

Slander cases (11%) were scandalous and spectacular. While some of the complaints may seem petty by our modern standards, they were a serious matter in colonial courts. The first case referenced above was about more than Thorowgood’s bruised ego and clearly sent a message to county residents. This was a very new community that was just coming together, as everyone had arrived within the prior 3-4 years when land grants were given. It was the beginning of local administration for this county and, while some justices might have known each other previously in Elizabeth City, it was the first time they were working together as a unit. It was also an era when respect and deference were expected: children to parents, servant to master, subject to the King and his envoys. Yet, cases sometimes revealed underlying resentment and anger against their successful leaders. [13]

There were no credit reports or personnel files that one could check, so gossip and lies spread in a community could damage not only a reputation, but also chances for getting credit, receiving governmental posts, advancing in society, and securing good marriages for one’s children. Although Ann Fowler did not attack Thorowgood in his role as a justice, the court apparently wanted everyone to know (at court and at church) that disrespectful and threatening speech would not be tolerated. Fortunately, the incident did not turn into a generational feud, for Adam’s grandson Argall Thorowgood eventually married Ann’s granddaughter Pembroke Fowler. [14]

The next year a more damaging accusation was levied at another justice, John Sibsey. Debra Glascocke, the wife of a carpenter, falsely accused Sibsey of having a child with one of his maids, for which Glascocke was given 100 stripes on her shoulders and required to ask forgiveness in court and at church. A similar punishment was given to Margaret Harrington when she accused, but could not prove, that Cornelius Loyd had abused the body of Sarah Julian, another justice’s wife. However, it was not just women who told such stories. When drunk, Thomas Davis falsely boasted that he had been with Anne Clarke and Richard Lowe falsely scandalized Anne Bitkings, a planter’s wife. They were both ordered to ask forgiveness and had to pay for the building of stocks. [15]

The next year a more damaging accusation was levied at another justice, John Sibsey. Debra Glascocke, the wife of a carpenter, falsely accused Sibsey of having a child with one of his maids, for which Glascocke was given 100 stripes on her shoulders and required to ask forgiveness in court and at church. A similar punishment was given to Margaret Harrington when she accused, but could not prove, that Cornelius Loyd had abused the body of Sarah Julian, another justice’s wife. However, it was not just women who told such stories. When drunk, Thomas Davis falsely boasted that he had been with Anne Clarke and Richard Lowe falsely scandalized Anne Bitkings, a planter’s wife. They were both ordered to ask forgiveness and had to pay for the building of stocks. [15]

In those two years, only one case of actual sexual misconduct was brought. Gov. Harvey sent to the county court a case in which a widow was seeking support for a child she had since had out of wedlock. The court ordered her to marry the father, Thomas Hughes, who was a servant of Capt. Willoughby, and for Capt. Willoughby to permit this and give them one bushel of corn. [16] There were likely other incidents of actual sexual misconduct in the county, but the court’s early responses may have made residents hesitant to make accusations that could not be proved.

Violent Offenses

Any violent felony cases would have gone to Jamestown, but there were no county reports or fact finding indicating such incidents occurred in those years. However, in 1638, the servants of John Sibsey in his absence raised a mutiny against his agent, William Edwards, for which they each received 100 stripes. The only reported assault involved the wounding of a fellow mariner “in a desperate and dangerous manner without cause” for which those sailors were returned to their ship and ordered to pay the surgeon when they reached England for the treatment of the wound. [17]

Any violent felony cases would have gone to Jamestown, but there were no county reports or fact finding indicating such incidents occurred in those years. However, in 1638, the servants of John Sibsey in his absence raised a mutiny against his agent, William Edwards, for which they each received 100 stripes. The only reported assault involved the wounding of a fellow mariner “in a desperate and dangerous manner without cause” for which those sailors were returned to their ship and ordered to pay the surgeon when they reached England for the treatment of the wound. [17]

Administrative Functions

The administrative duties assigned to the court included approval of property exchanges, awarding land for bringing headrights to the Colony, and assigning property appraisals. The court also assessed residents for maintaining ferries, secured workmen to build a church, selected the Burgesses with the consent of the freemen, and offered a bounty of 50 lb. tobacco for each wolf head because of “the divers and many damages done unto cattle…by the multitude of wolves which do frequent the woods and plantations.”

The Governor and Assembly set the policy for dealing with Indians, and in 1639 they ordered the county court to conscript “fifteen sufficient men” with food and supplies to march against the Nanticoke Tribe of the Eastern Shore, even though they were not a threat to the Lower Norfolk area. The court also provided licenses to bargain with the Indians, and Christopher Burroughs received a 500 lb. tobacco fine when he bargained without one. [18]

The Governor and Assembly set the policy for dealing with Indians, and in 1639 they ordered the county court to conscript “fifteen sufficient men” with food and supplies to march against the Nanticoke Tribe of the Eastern Shore, even though they were not a threat to the Lower Norfolk area. The court also provided licenses to bargain with the Indians, and Christopher Burroughs received a 500 lb. tobacco fine when he bargained without one. [18]

The Court Moves On

The death of Adam Thorowgood was unexpected in the winter of 1639/40, but, of course, the court proceeded on. Thomas Willoughby was appointed the presiding justice, and the court continued to rotate being held at the homes of justices until May 1646 when it was decided that all future courts should be held at the tavern of William Shipp on the Eastern Branch of the Elizabeth River. It was not only convenient, but also provided desirable refreshments. In 1655, the Norfolk commissioners ordered that a market and church should also be built for the Elizabeth Parish on Mr. Shipp’s land. As the General Assembly had ordered a similar set up of church, court, and market in each parish, plans were made to also build on Thorowgood land, but the order was rescinded before it was done. However, in January 1660, the first Lower Norfolk County court house was finally designated to be built at Thomas Harding’s plantation on Broad Creek off the Elizabeth River. Although its exact location is not known, it was near today’s dividing line between Norfolk and the City of Virginia Beach. [19]

The death of Adam Thorowgood was unexpected in the winter of 1639/40, but, of course, the court proceeded on. Thomas Willoughby was appointed the presiding justice, and the court continued to rotate being held at the homes of justices until May 1646 when it was decided that all future courts should be held at the tavern of William Shipp on the Eastern Branch of the Elizabeth River. It was not only convenient, but also provided desirable refreshments. In 1655, the Norfolk commissioners ordered that a market and church should also be built for the Elizabeth Parish on Mr. Shipp’s land. As the General Assembly had ordered a similar set up of church, court, and market in each parish, plans were made to also build on Thorowgood land, but the order was rescinded before it was done. However, in January 1660, the first Lower Norfolk County court house was finally designated to be built at Thomas Harding’s plantation on Broad Creek off the Elizabeth River. Although its exact location is not known, it was near today’s dividing line between Norfolk and the City of Virginia Beach. [19]

In a study of the crimes and misdemeanors (excluding debts and administrative decisions) in Lower Norfolk County from 1637 until 1675 just before Bacon’s Rebellion, James Horn found that serious crimes increased. While property offenses were 13.5%, including theft (6%) and killing of livestock (5%), violent crimes increased to 11% with 13 murders (2.7%) and 23 physical assaults (4.8%). Defamation continued to be a problem (23.4%), and there was a significant increase in reported sexual offenses (30%). Contempt of court and challenges to authority made up 12% with another 10% miscellaneous charges, including 2 accusations of witchcraft. [20]

In a study of the crimes and misdemeanors (excluding debts and administrative decisions) in Lower Norfolk County from 1637 until 1675 just before Bacon’s Rebellion, James Horn found that serious crimes increased. While property offenses were 13.5%, including theft (6%) and killing of livestock (5%), violent crimes increased to 11% with 13 murders (2.7%) and 23 physical assaults (4.8%). Defamation continued to be a problem (23.4%), and there was a significant increase in reported sexual offenses (30%). Contempt of court and challenges to authority made up 12% with another 10% miscellaneous charges, including 2 accusations of witchcraft. [20]

Using their understandings of English common law, the justices of the Lower Norfolk County courts did their best to maintain the peace and provide justice according to the challenges of Virginia. However, it took over three decades for help to arrive. It fell to Adam Thorowgood II on a trip to England in 1671 to fulfill the request of the Lower Norfolk County justices regarding

the act of assembly to provide several law books for the use of our county court and …request you bring with you at your return for the county court’s use these several books, viz: The Statutes at Large, a Doultan’s Justice of Peace and Office of Sheriff, and Swinborne’s Book of Wills and Testaments.[21]

Next Post: Thorowgood and the Council of Ousted Gov. John Harvey: Roots of Rebellion

Also see:

Becoming a Virginia Burgess in 1629

English Settlers to Virginia Beach: Who’s First?

Adam Thorowgood, Slavery, and 17th Century Racism

Envisioning 17th Century Virginia Great Houses

Footnotes:

[1] Mason, George Carrington, “The Courthouses of Princess Anne and Norfolk Counties'” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, 57:4 (October, 1949), 405- 406.

[2] Walter, Alice Granbery, Lower Norfolk County, Virginia Court Book “A” (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., Inc., 1994), 1.

[3] Billings, Warren M., The Old Dominion in the Seventeenth Century (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007), 87. McCartney, Martha W. Virginia Immigrants and Adventurers 1607-1635: A Biographical Dictionary (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company, 2007), 692. Turner, Florence K., Gateway to the New World: A History of Princess Anne County, Virginia 1607-1824 (Easley, South Carolina: Southern Historical Press, Inc., 1984), 33.

[4] Walter, 1-2. Brown, Kathleen M., Good Wives, Nasty Wenches, and Anxious Patriarchs: Gender, Race and Power in Colonial Virginia (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996), 95.

[5] Horn, James, Adapting to a New World: English Society in the Seventeenth-Century Chesapeake (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1994), 339. Nelson, William E., The Common Law in Colonial America, Volume 1: The Chesapeake and New England 1607-1660 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 26.

[6] Billings, 84-87. Horn, 351-352.

[7] Horn, 338-341. McCartney, 436, 482, 638, 629, 755.

[8] Horn, 337. Nelson, 26-27, 39.

[9] Walter, 103. Cross, Charles B. and Eleanor Phillips Cross, Chesapeake: A Pictorial History (Norfolk, Va.: Donning Co. Publishers, 1985), 18-19.

[10] Nelson, 7-9.

[11] Walter, 1- 21

[12] Ibid.

[13] Brown, 99. Horn, 342-345. Walter, 1-21.

[14] Turner, 36.

[15] Brown, 99. Walter, 2, 8, 9.

[16] Walter, 2.

[17] Walter, 7, 17.

[18] Cross, 18-19. Walter, 1-21.

[19] Cross, 18-20. Mason, 406-407.

[20] Horn 346-347.

[21] Turner, 49. Nelson 29.

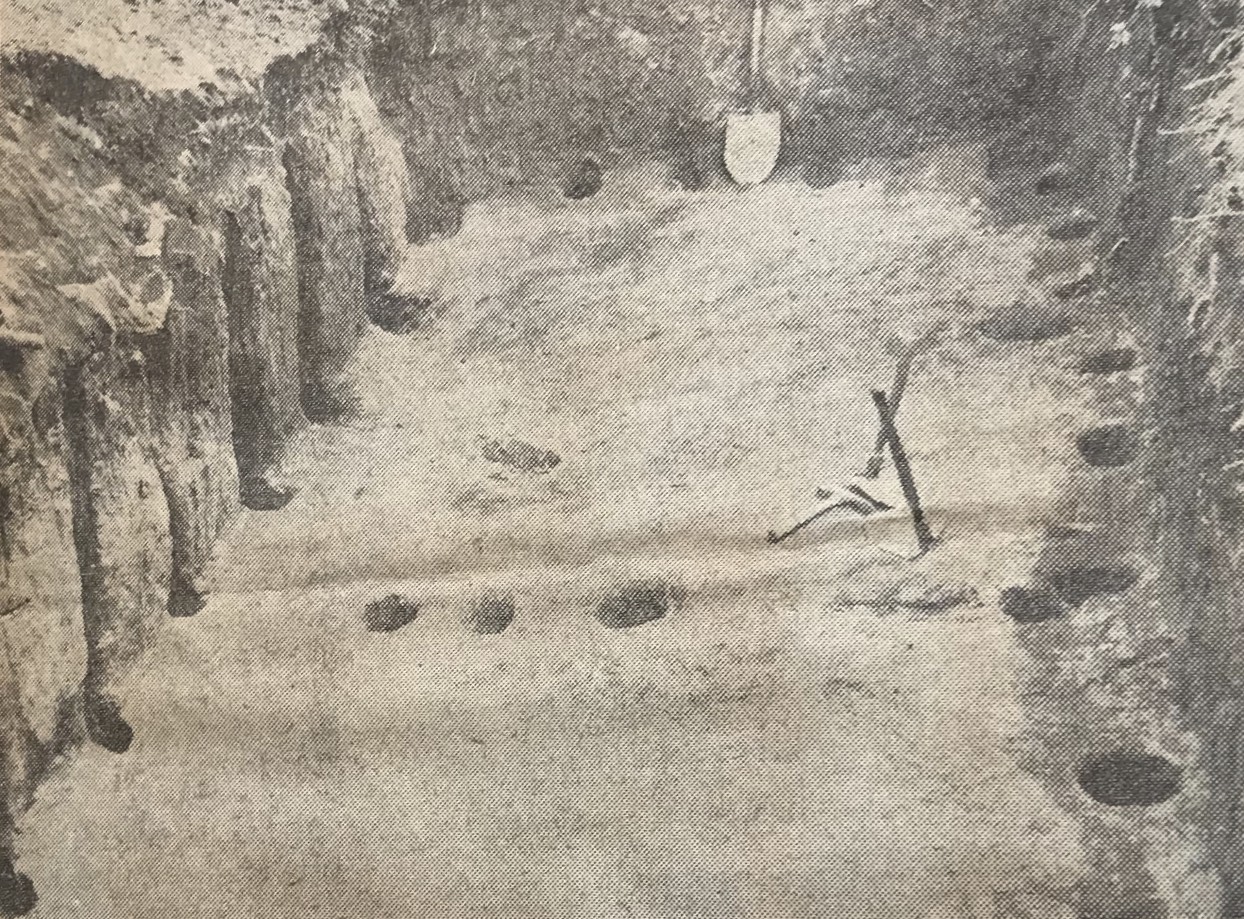

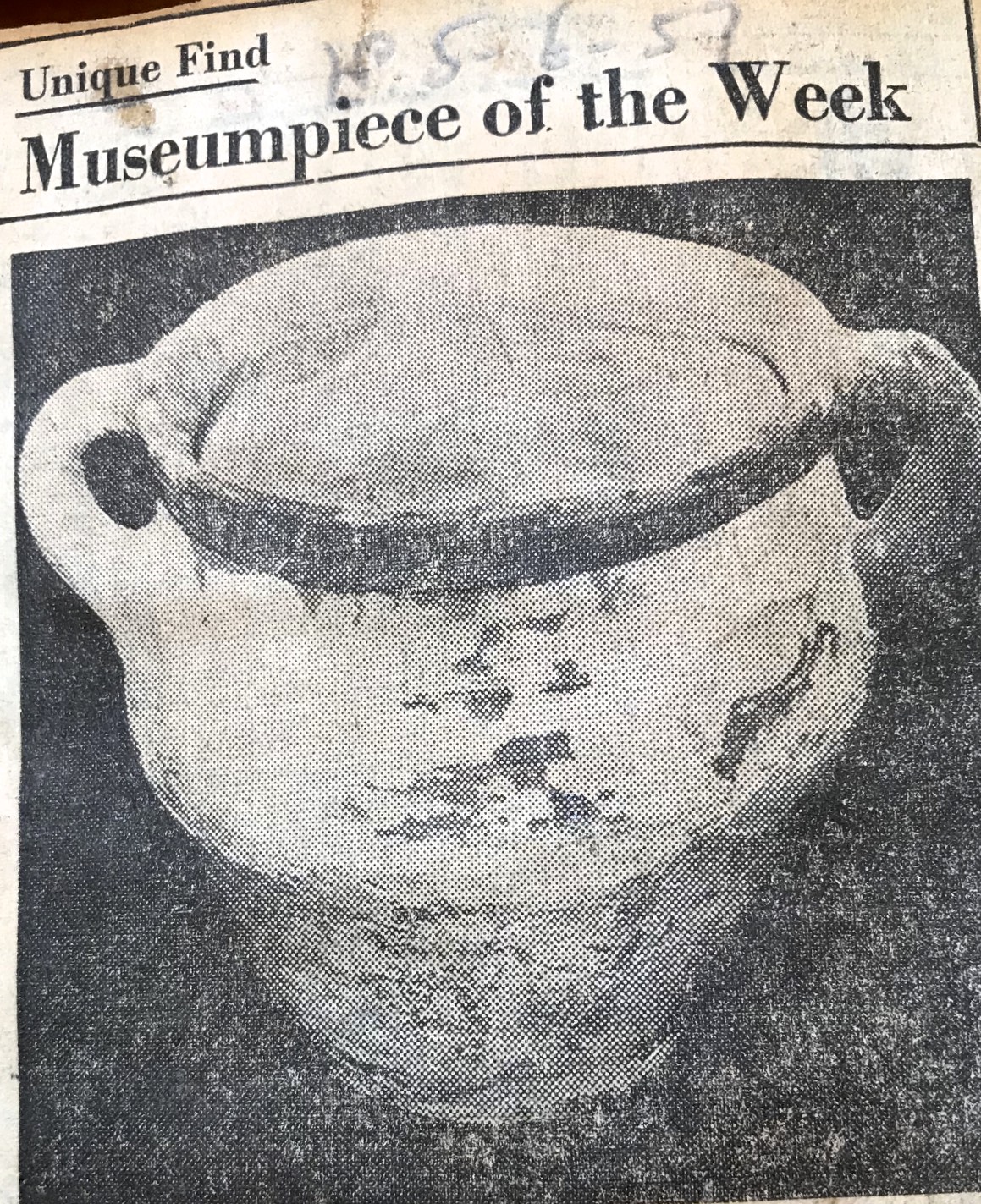

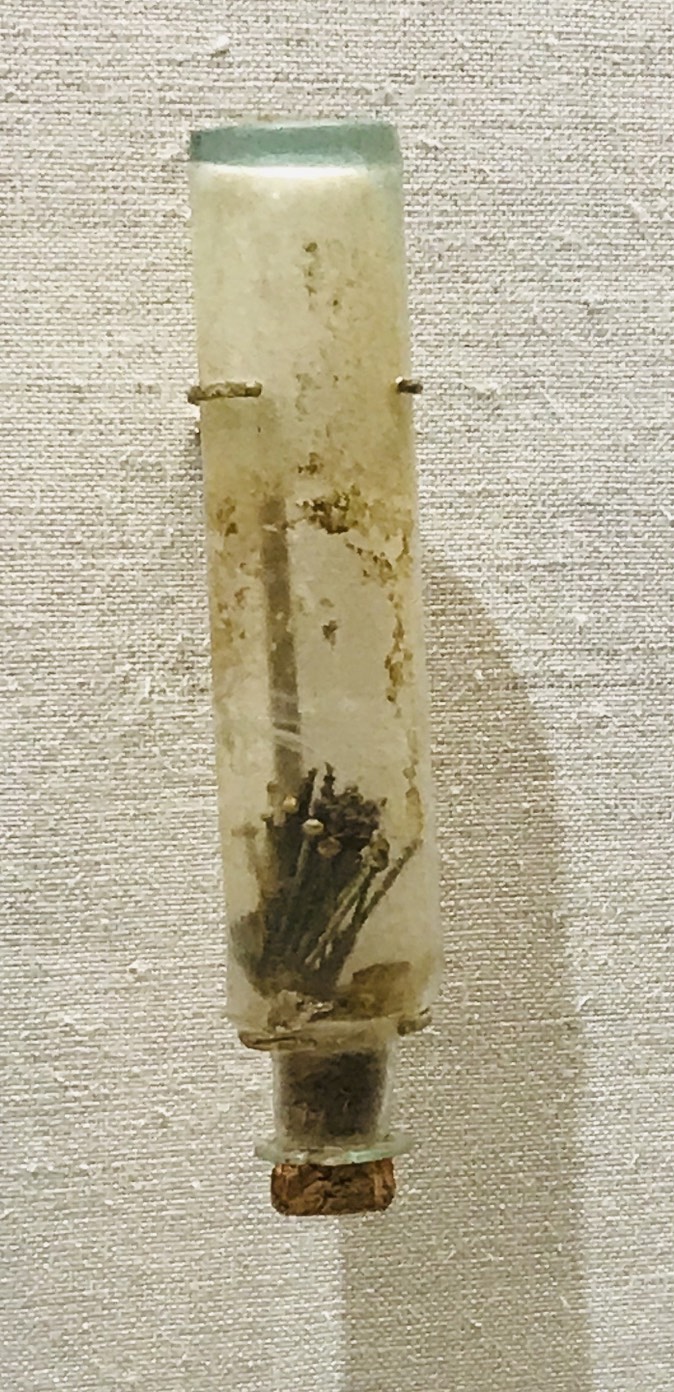

Most of the artifacts found were dated from the 17th century. There were some homemade bricks with old mortar still attached that appeared to have been used for a chimney. The house also had glass windows evidenced by melted lead cames that would have been used between diamond-shaped glass. The house appeared to have burned to the ground in the 1650s and was not rebuilt. After the fire, it seemed that the cellar was used as a trash pit “where the occupational debris was thrown: broken crockery, chamber pots, bones of animals eaten for food, sword hilts, bits of iron, pipe fragments….” Of particular interest was a broken large bread platter with the letters “TH”, a bone comb, bone utensil handles, and a silver “apostle” spoon. Shortly after the dig, Malcolm Walkings, the associate curator for the Smithsonian, confirmed that the artifacts dated between 1610-1660, including many of the popular Dutch ceramics. [3] As most Virginians were living in one room houses at that time without glass in their windows, this had clearly been the home of a wealthy family.

Most of the artifacts found were dated from the 17th century. There were some homemade bricks with old mortar still attached that appeared to have been used for a chimney. The house also had glass windows evidenced by melted lead cames that would have been used between diamond-shaped glass. The house appeared to have burned to the ground in the 1650s and was not rebuilt. After the fire, it seemed that the cellar was used as a trash pit “where the occupational debris was thrown: broken crockery, chamber pots, bones of animals eaten for food, sword hilts, bits of iron, pipe fragments….” Of particular interest was a broken large bread platter with the letters “TH”, a bone comb, bone utensil handles, and a silver “apostle” spoon. Shortly after the dig, Malcolm Walkings, the associate curator for the Smithsonian, confirmed that the artifacts dated between 1610-1660, including many of the popular Dutch ceramics. [3] As most Virginians were living in one room houses at that time without glass in their windows, this had clearly been the home of a wealthy family.

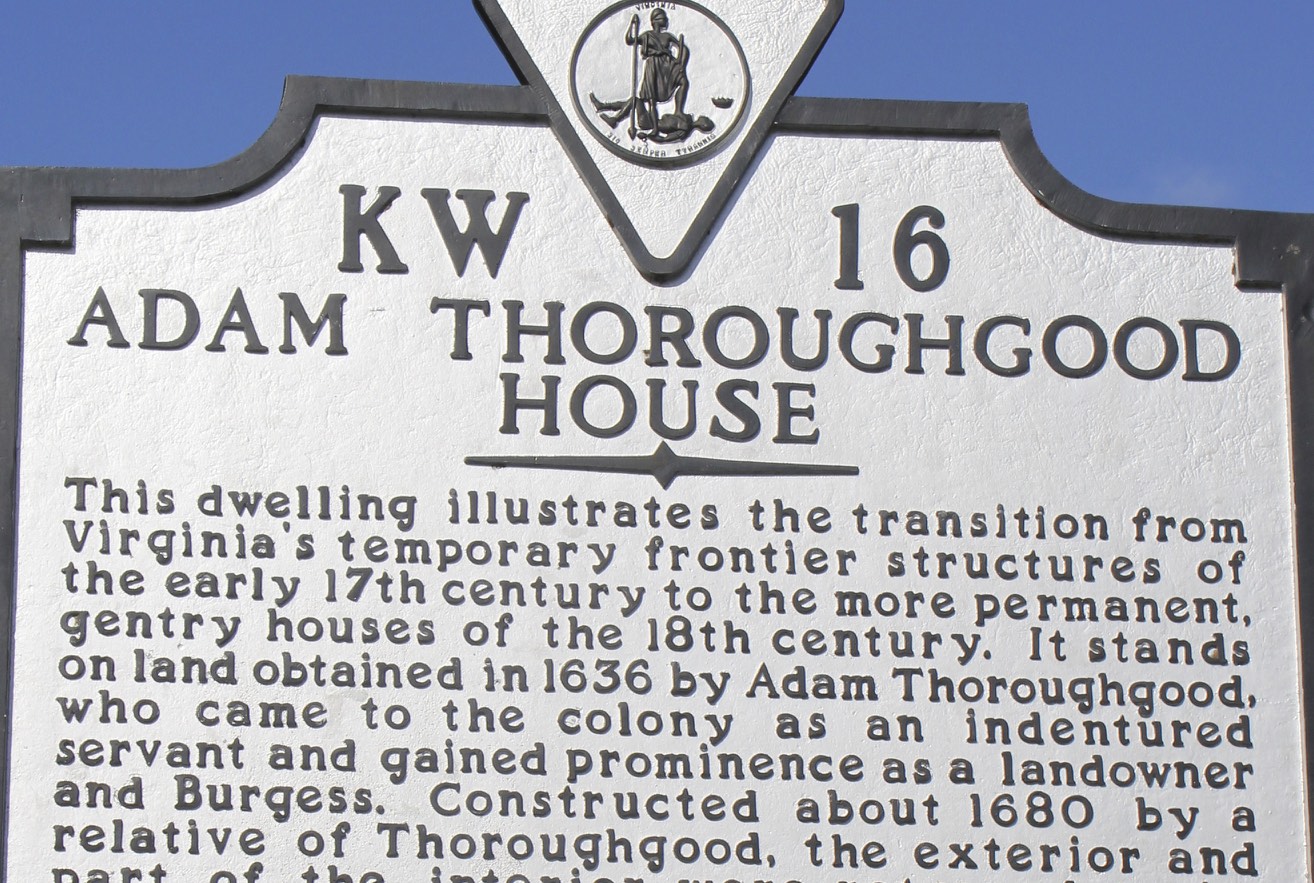

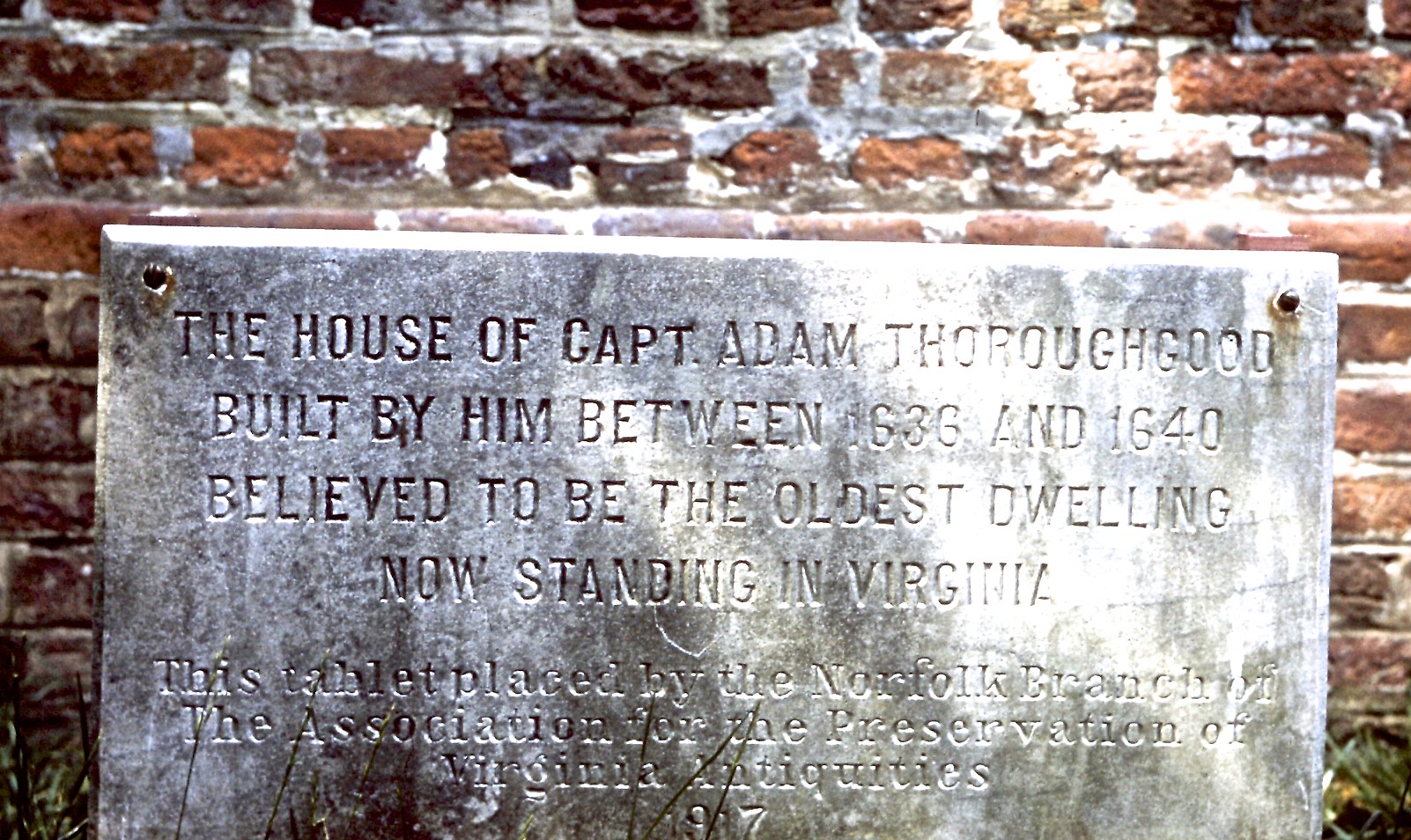

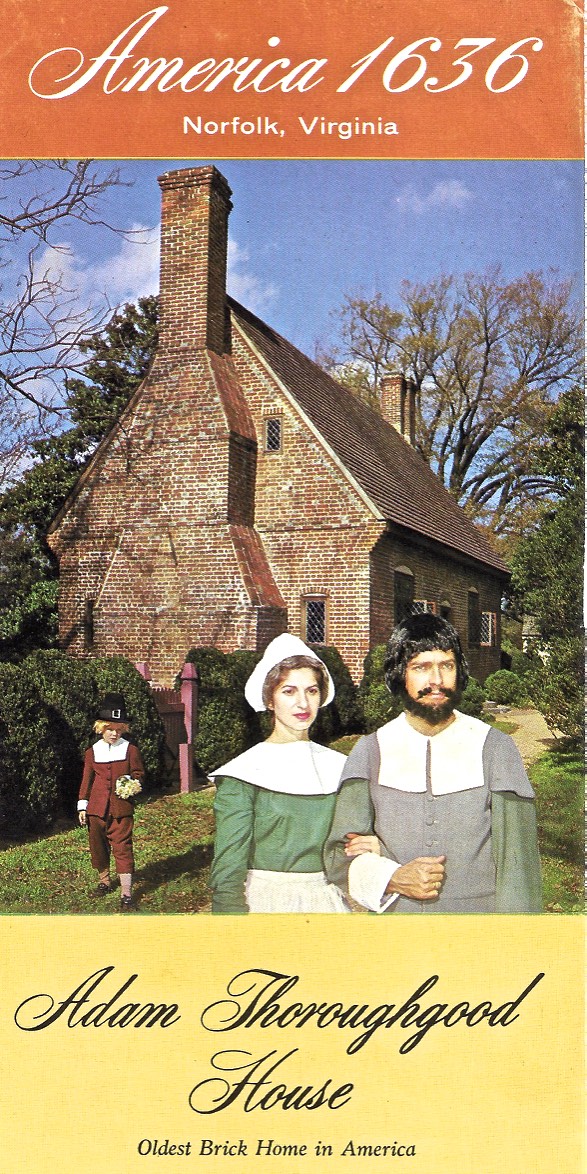

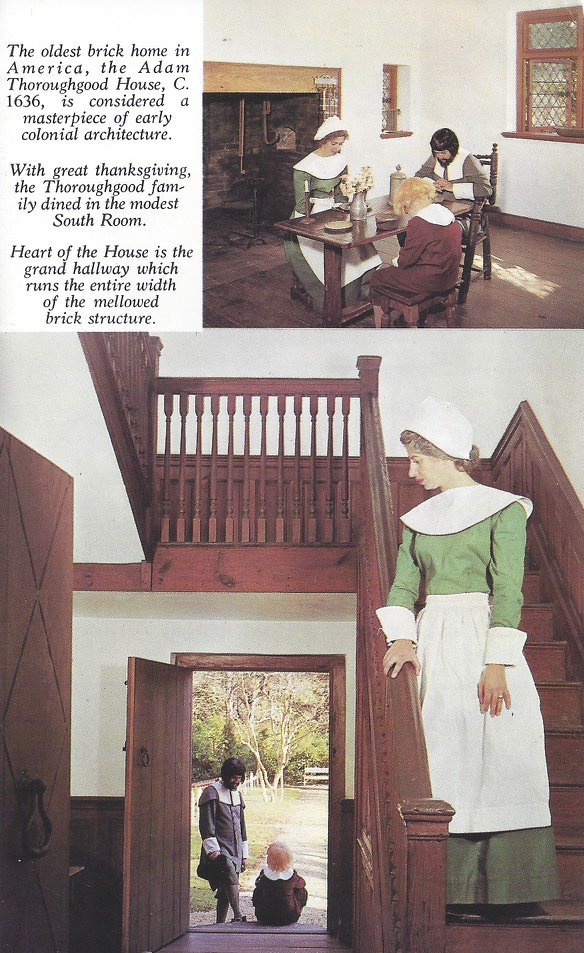

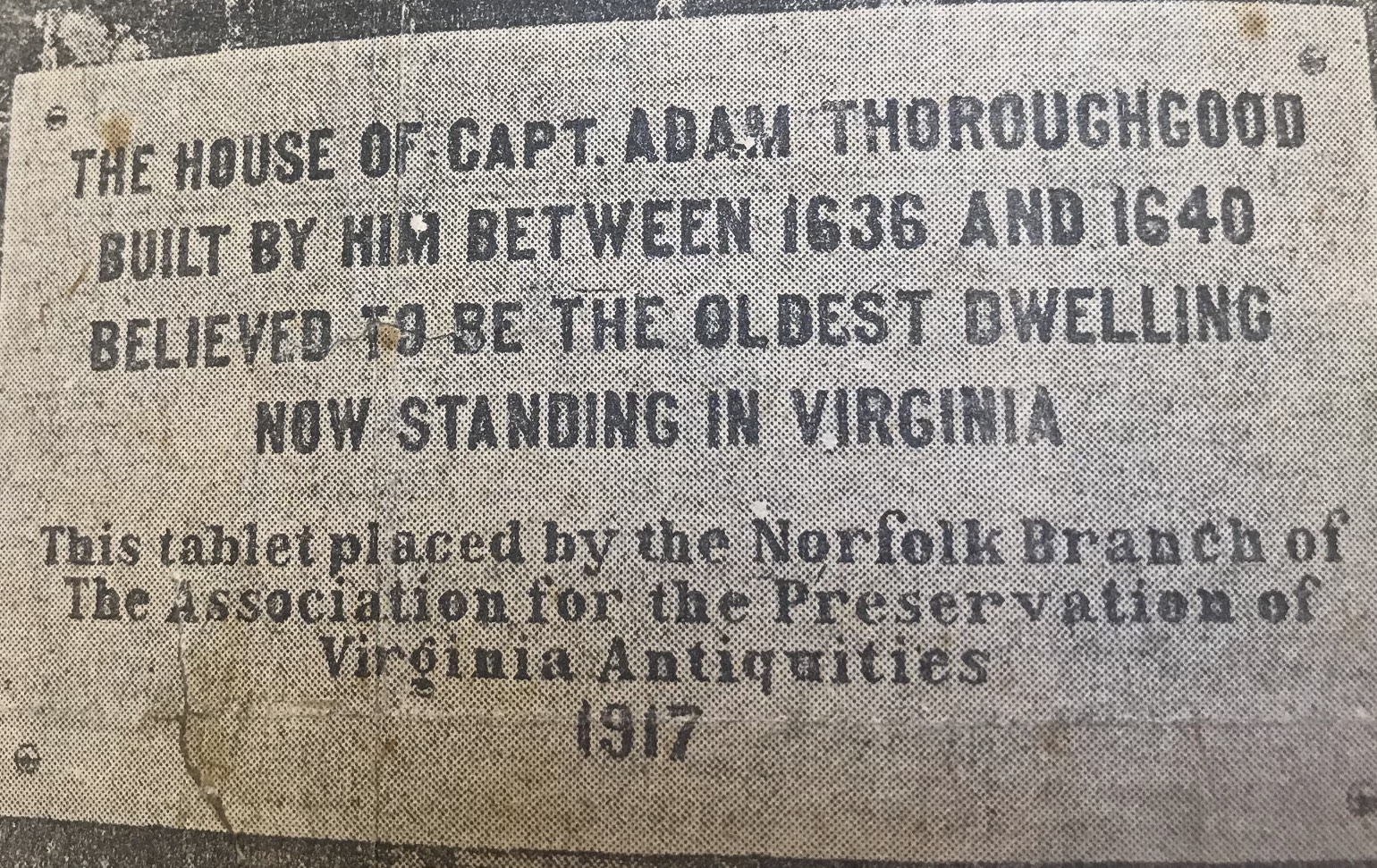

Around the same time as Painter’s discovery, the brick “Adam Thoroughgood” House became a museum and opened in time for the 350th anniversary of the founding of Jamestown in 1957. While there have been revisions to the dating of the house, it has consistently shared the story of one of the important founders of Virginia Beach. In May 2018, after an extensive maintenance closure, the Thoroughgood House was rededicated and now is shown as an early 18th century home. A new Education Center on the site tells the expanded and inclusive story of the Thorowgoods in Virginia Beach through the American Revolution. Even if it is not the 17th century home it was once believed to be, the Thoroughgood House is still architecturally and historically significant and worth a visit when it reopens after the pandemic. (See

Around the same time as Painter’s discovery, the brick “Adam Thoroughgood” House became a museum and opened in time for the 350th anniversary of the founding of Jamestown in 1957. While there have been revisions to the dating of the house, it has consistently shared the story of one of the important founders of Virginia Beach. In May 2018, after an extensive maintenance closure, the Thoroughgood House was rededicated and now is shown as an early 18th century home. A new Education Center on the site tells the expanded and inclusive story of the Thorowgoods in Virginia Beach through the American Revolution. Even if it is not the 17th century home it was once believed to be, the Thoroughgood House is still architecturally and historically significant and worth a visit when it reopens after the pandemic. (See

Since Biblical times, good Christians had been taught to fear the Devil and his evil spirits, but around the 14th century, suspicions developed that the odd ones living in their communities might have sold their souls to the Devil and contracted to do his biding.

Since Biblical times, good Christians had been taught to fear the Devil and his evil spirits, but around the 14th century, suspicions developed that the odd ones living in their communities might have sold their souls to the Devil and contracted to do his biding.

As the trial was in September, it is unknown whether Adam had returned to England before the trial started. However, having lived in Kecoughtan the previous years as part of Edward Waters’ household, he may well have known the Wrights or at least heard talk of Joan’s suspicious activities. According to the surviving

As the trial was in September, it is unknown whether Adam had returned to England before the trial started. However, having lived in Kecoughtan the previous years as part of Edward Waters’ household, he may well have known the Wrights or at least heard talk of Joan’s suspicious activities. According to the surviving  Joan Wright had been asked by Lt. Allington, to attend to his pregnant wife as the midwife, but when the wife discovered that Joan was left-handed and heard the rumors about her, she refused her and had another midwife brought. When Goodwife Wright found out, she was upset. The Allingtons believed she therefore cursed them, and consequently, each sequentially became ill (although of different disorders). Even though they all recovered, the infant succumbed after a second illness more than a month after its birth.

Joan Wright had been asked by Lt. Allington, to attend to his pregnant wife as the midwife, but when the wife discovered that Joan was left-handed and heard the rumors about her, she refused her and had another midwife brought. When Goodwife Wright found out, she was upset. The Allingtons believed she therefore cursed them, and consequently, each sequentially became ill (although of different disorders). Even though they all recovered, the infant succumbed after a second illness more than a month after its birth.

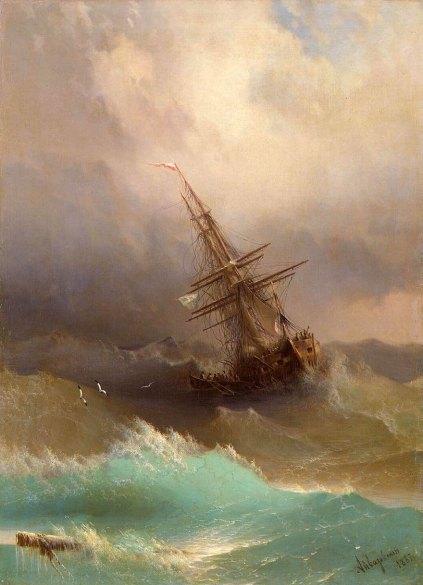

The Virginia justices found most of the accusations of witchcraft unsubstantiated. The only guilty verdict that remains is for William Harding of the Northern Neck in Virginia, who was accused by his Scottish preacher of witchcraft and sorcery in 1656. The accusations must not have been too serious, for his punishment was only ten lashes and banishment from the county. Nor were the citizens overly concerned, as he was given two months to leave. Katherine Grady was the only suspected witch to be hung, but it was done before she even reached Virginia in 1654 and under the direction of the ship’s captain, not court justices. When the ship encountered a severe storm near the end of its journey, the passengers were convinced that Katherine had caused it through witchcraft. Upon reaching Jamestown, the Captain had to appear before the admiralty court, but its findings have been lost.

The Virginia justices found most of the accusations of witchcraft unsubstantiated. The only guilty verdict that remains is for William Harding of the Northern Neck in Virginia, who was accused by his Scottish preacher of witchcraft and sorcery in 1656. The accusations must not have been too serious, for his punishment was only ten lashes and banishment from the county. Nor were the citizens overly concerned, as he was given two months to leave. Katherine Grady was the only suspected witch to be hung, but it was done before she even reached Virginia in 1654 and under the direction of the ship’s captain, not court justices. When the ship encountered a severe storm near the end of its journey, the passengers were convinced that Katherine had caused it through witchcraft. Upon reaching Jamestown, the Captain had to appear before the admiralty court, but its findings have been lost. This was put to the test in 1698 when John and Ann Byrd sued Charles Kinsey and John Potts for having “falsely and scandalously” defamed them by claiming they were witches and “in league with the Devil.” Kinsey finally admitted to the court that he might have only dreamed that they “had rid him along the Seaside and home” through witchcraft . John Thorowgood, a son of Adam Thorowgood II, was one of the justices on that court which surprisingly did not give a cash award to the Byrds, but rather found for the defendants. However, they chose not to pursue witchcraft charges against the Byrds.

This was put to the test in 1698 when John and Ann Byrd sued Charles Kinsey and John Potts for having “falsely and scandalously” defamed them by claiming they were witches and “in league with the Devil.” Kinsey finally admitted to the court that he might have only dreamed that they “had rid him along the Seaside and home” through witchcraft . John Thorowgood, a son of Adam Thorowgood II, was one of the justices on that court which surprisingly did not give a cash award to the Byrds, but rather found for the defendants. However, they chose not to pursue witchcraft charges against the Byrds.

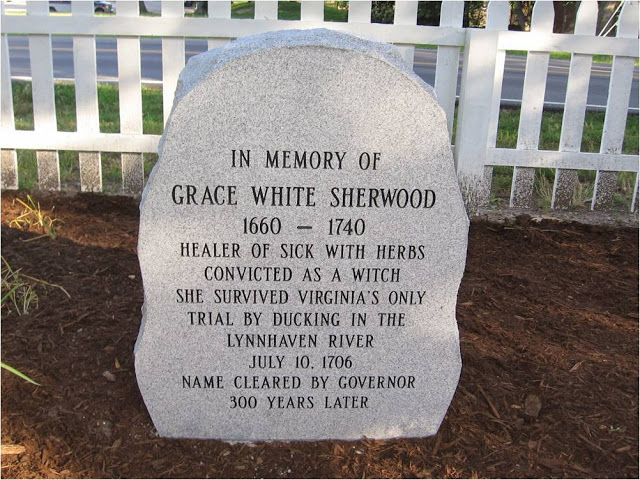

In 1705, Elizabeth Hill, another neighbor, called Grace a witch, and a brawl between them ensued. Grace filed a complaint of trespassing and assault and battery against Elizabeth. Although Grace prevailed, she received little in monetary damages. Elizabeth Hill’s husband then made a formal charge of witchcraft against her. Accusations included that no grass would grow where she had danced in the moonlight, that she had soured the cow’s milk, and that she had made herself small enough to fly in an eggshell to England and back in one night to get rosemary seeds for her garden. However, rosemary was abundant locally and, ironically, often used to protect against witches.

In 1705, Elizabeth Hill, another neighbor, called Grace a witch, and a brawl between them ensued. Grace filed a complaint of trespassing and assault and battery against Elizabeth. Although Grace prevailed, she received little in monetary damages. Elizabeth Hill’s husband then made a formal charge of witchcraft against her. Accusations included that no grass would grow where she had danced in the moonlight, that she had soured the cow’s milk, and that she had made herself small enough to fly in an eggshell to England and back in one night to get rosemary seeds for her garden. However, rosemary was abundant locally and, ironically, often used to protect against witches.

Virginia Beach has erected a kindly statue in honor of this misunderstood woman, and the Governor of Virginia recently pardoned her, even though there is no record of her conviction. Grace seems not to have had the sweet disposition portrayed in the statue, but still she serves as a symbol of those innocent “

Virginia Beach has erected a kindly statue in honor of this misunderstood woman, and the Governor of Virginia recently pardoned her, even though there is no record of her conviction. Grace seems not to have had the sweet disposition portrayed in the statue, but still she serves as a symbol of those innocent “

Witchcraft and the occult are still practiced by some today. While there are those who try to connect with the spirit of the earth and be “good witches,” there are others who have carried out horrific acts. Unfortunately, over the ages, many innocents were sent to their deaths because of the superstitions and suspicions of others. It has been estimated that 85% of those killed in European witch hunts were women. A Puritan preacher of the time, William Perkins, was unapologetic in his explanation:

Witchcraft and the occult are still practiced by some today. While there are those who try to connect with the spirit of the earth and be “good witches,” there are others who have carried out horrific acts. Unfortunately, over the ages, many innocents were sent to their deaths because of the superstitions and suspicions of others. It has been estimated that 85% of those killed in European witch hunts were women. A Puritan preacher of the time, William Perkins, was unapologetic in his explanation:

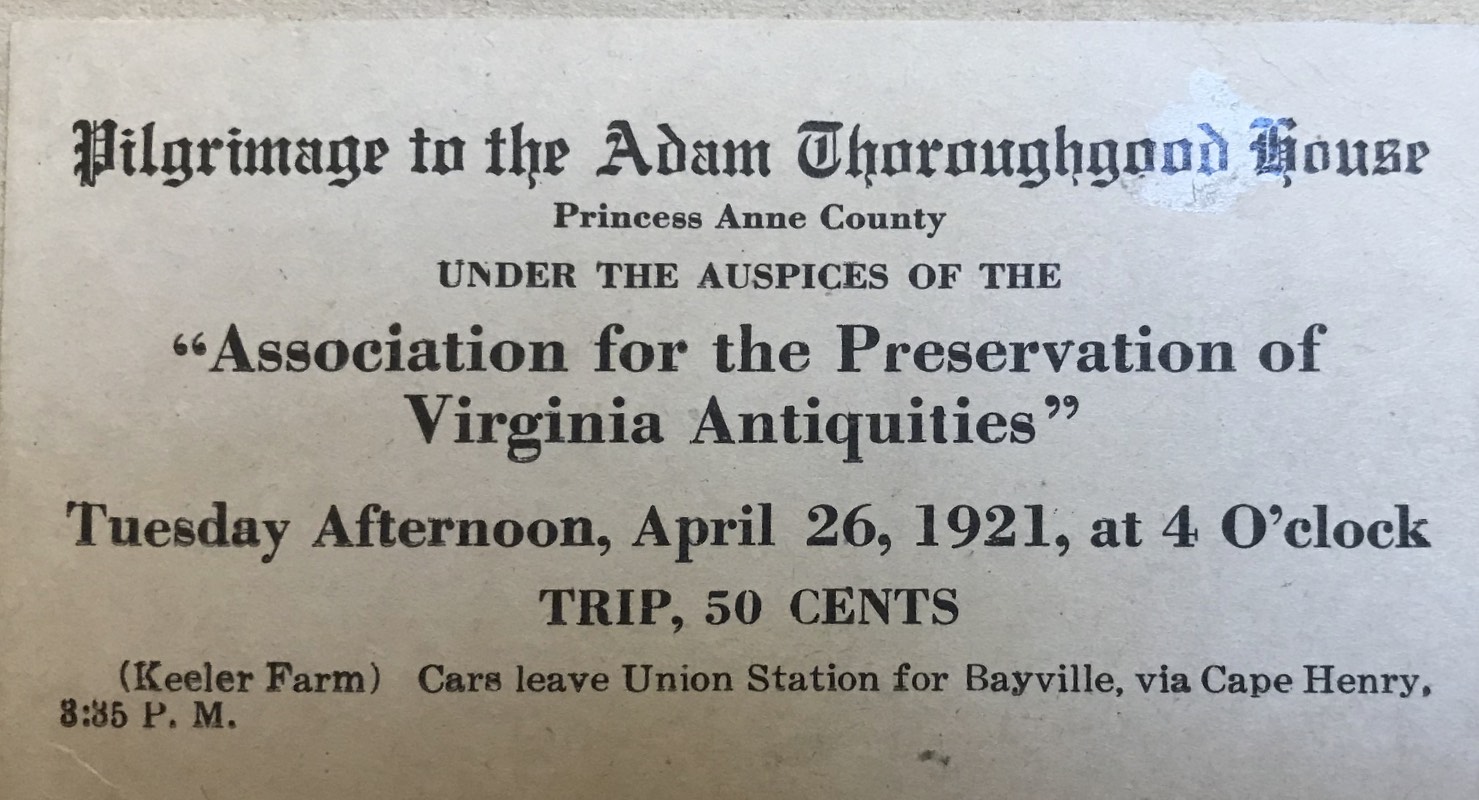

transfers, the old house and 2+acres of land were sold to the Thoroughgood Foundation for preservation, while a larger parcel was used by the Thorogood Corportation for development. (I know my spelling looks inconsistent, but that is the way things were spelled). The Norfolk APVA Branch watched to be sure the old house would survive. After a few years, it was deeded to the City of Norfolk.

transfers, the old house and 2+acres of land were sold to the Thoroughgood Foundation for preservation, while a larger parcel was used by the Thorogood Corportation for development. (I know my spelling looks inconsistent, but that is the way things were spelled). The Norfolk APVA Branch watched to be sure the old house would survive. After a few years, it was deeded to the City of Norfolk.

and historical architecture matured. There were new and more refined techniques and a broader base of knowledge than had been available to the prior professionals. Unfortunately, in the early “restorations,” original 18th century features that did not fit the 17th century interpretation were altered, including windows, paneling, upstairs partitions, and dormers. Thus, the very efforts to preserve the house had actually removed and obscured clues to its real identity.

and historical architecture matured. There were new and more refined techniques and a broader base of knowledge than had been available to the prior professionals. Unfortunately, in the early “restorations,” original 18th century features that did not fit the 17th century interpretation were altered, including windows, paneling, upstairs partitions, and dormers. Thus, the very efforts to preserve the house had actually removed and obscured clues to its real identity. , it was decided that the brick house was not built by Adam, the immigrant, but rather by “a relative of Thoroughgood” around 1680. However, that compromise on dates did not fit the other unraveling facts nor satisfy the critics.

, it was decided that the brick house was not built by Adam, the immigrant, but rather by “a relative of Thoroughgood” around 1680. However, that compromise on dates did not fit the other unraveling facts nor satisfy the critics.

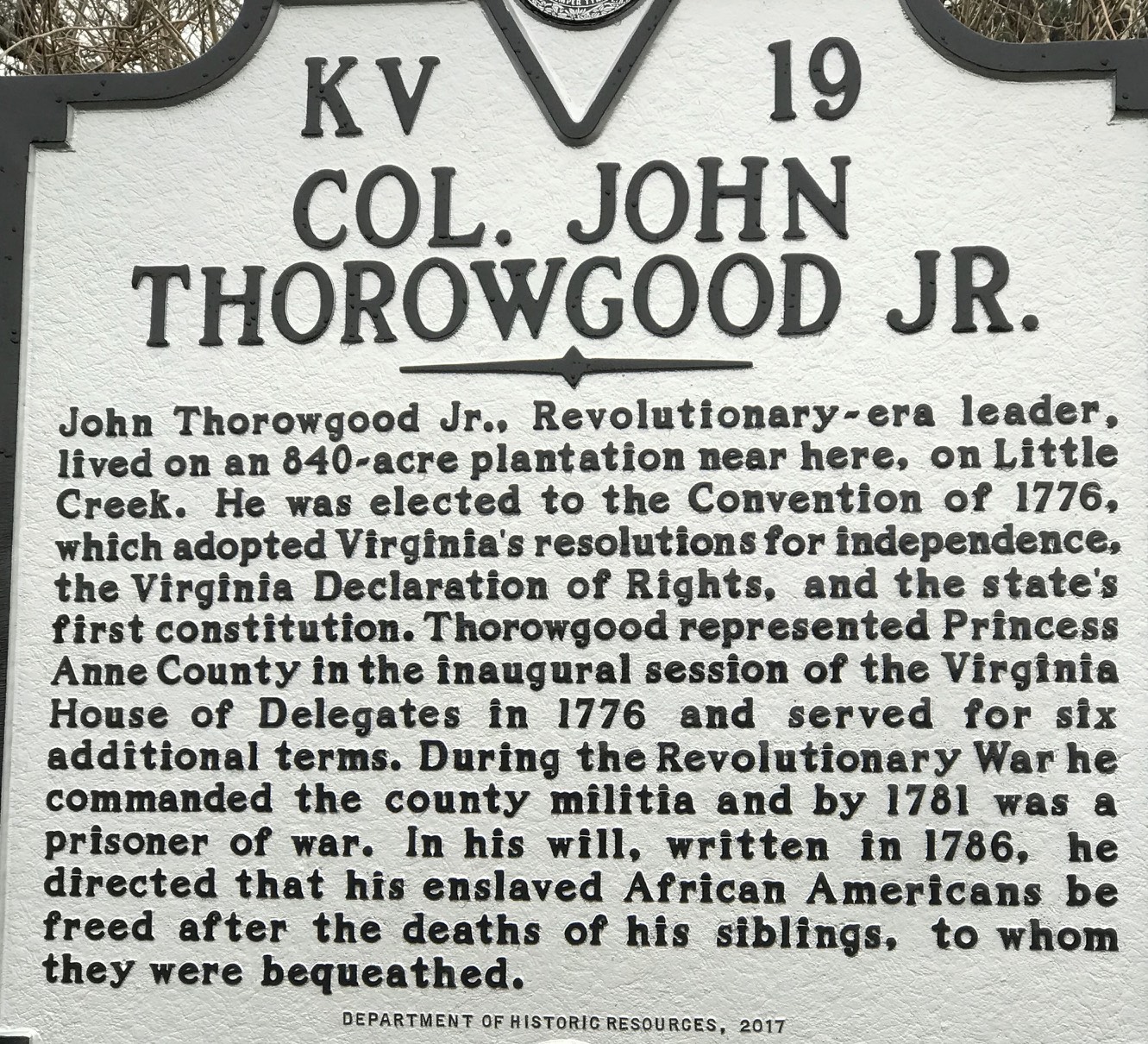

Princess Anne area, the Thorowgoods were known Patriots. On the

Princess Anne area, the Thorowgoods were known Patriots. On the

05-1913 and in articles in The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography starting in 1893.

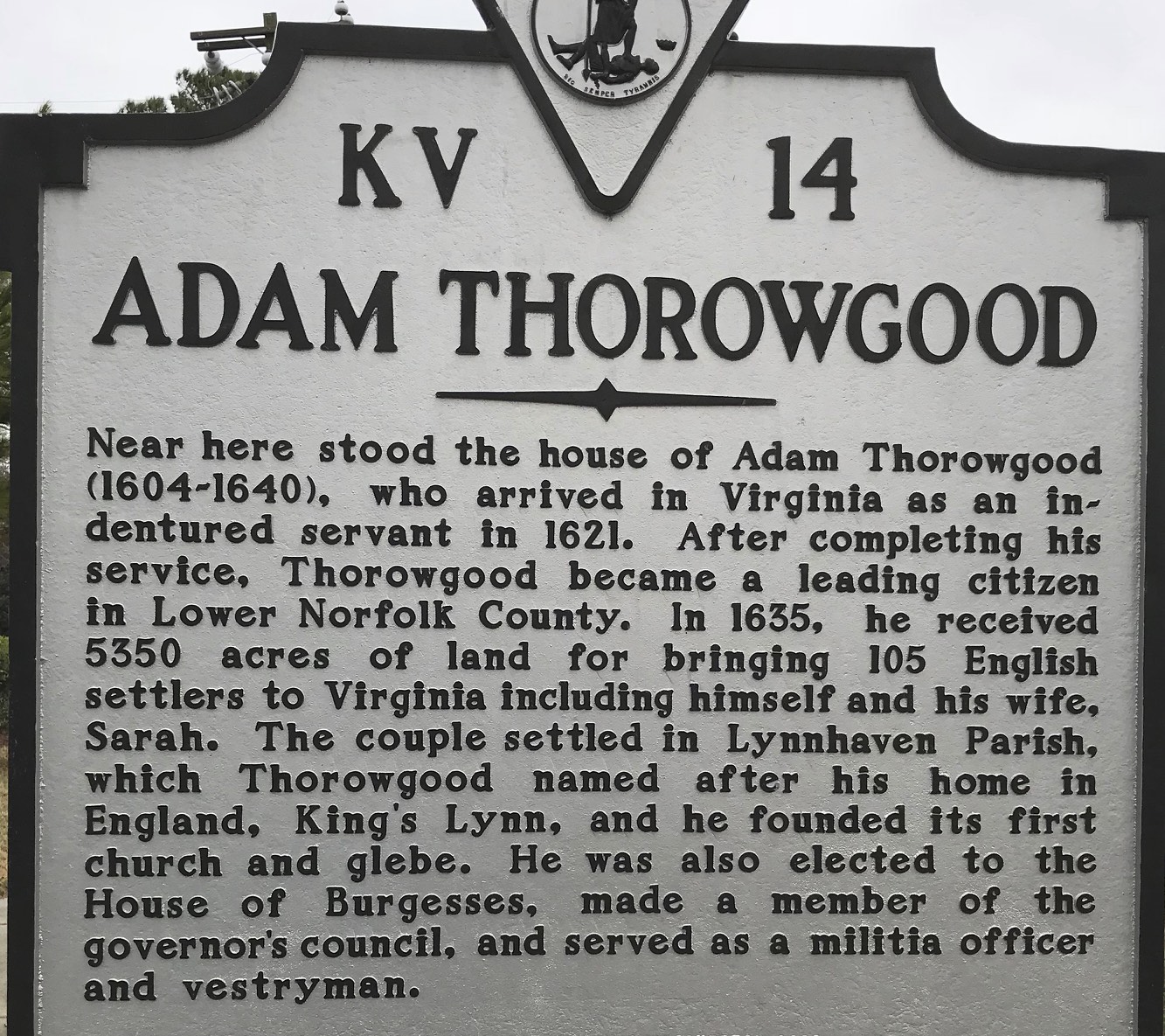

05-1913 and in articles in The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography starting in 1893. Recently, though, there has been a return to the original spelling. In 2006, a Virginia State Highway marker was added in Virginia Beach for Adam Tho

Recently, though, there has been a return to the original spelling. In 2006, a Virginia State Highway marker was added in Virginia Beach for Adam Tho