Adam Thorowgood’s luck finally ran out in the winter of 1639/40. For 19 years, he had prospered in Virginia, skirting fatal fevers, salt poisoning, Powhatan attacks, trans-Atlantic mishaps, and political intrigues. When Adam accepted the prestigious appointment as a member of the Governor’s Council in 1637, he surely thought it would open greater opportunities, not lead to his death. Adam’s will was dated February 17, 1639/40 and was entered into probate at the Quarter Court held in James City on April 27, 1640. As the Julian Calendar was still in use in England, the year did not end until March 25th which created confusions even at that time, as most of Europe had already changed to the Gregorian Calendar which began with January 1. Thus, Adam’s will was probated 8 weeks after being written, not a year and eight weeks later. The original copy of Adam’s will as recorded in James City no longer exists, but fortunately the content was preserved when it was printed in The Richmond Standard by one of his descendants in 1881. [1]

Adam had presided at the Lower Norfolk County Court on October 18, 1639. He likely passed the Christmas season at home with his family, although being of a Puritan persuasion, there would have been little celebration. Adam and several of his servants then traveled to James City to attend the General Assembly convened on January 6, 1639/40 by Governor Francis Wyatt who had just replaced the disgraced Gov. Harvey. Under the new leadership, it was a busy and productive session with 34 Acts passed. [2] We do not know when it concluded, but somehow and sometime in that period, Adam Thorowgood and his accompanying servants took ill. Within weeks, Adam died.

Treatment by Dr. George Calvert

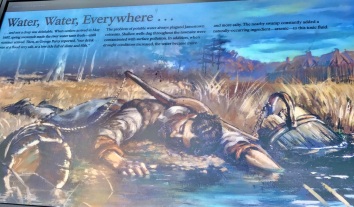

Killing fevers were the scourge of Jamestown, but they could result from many disorders. Adam Thorowgood had been fortunate to spend his “seasoning” period in the vicinity of Elizabeth City and the rest of his time in Virginia mostly away from the disease-ridden Jamestown. It is not known what killed Adam. It was not the season for malaria, and “remittent fevers” were more likely in the spring and fall, although scarlatine fever was found year round. Contaminated food and water were common and could lead to typhoid fever or bloody flux (dysentery) at any season. Influenza, more typical in the fall or winter, was also a common cause of fever deaths. [3]

In 1610, Dr Lawrence Bohune was the first English physician sent to the Virginia Colony. Dr. John Pott was sent to replace him in 1620, but few trained doctors followed in subsequent years. Physician services were so expensive that the General Assembly noted in 1639 the “immoderate and excessive rates and prices exacted by practitioners in physick and chyrurgery.”. Most Virginians tried herbs and remedies on their own, sometimes seeking out a surgeon instead of a physician as they were cheaper, though not as well regarded or trained. Despite their political differences, Gov. John Harvey even asked the English courts to overturn a 1630 Virginia court conviction of Dr. Pott because he was “the only physician in Virginia skilled in epidemical diseases” at the time. In 1639/40 when Adam became ill, Dr. Pott had moved to the area that would become Williamsburg, but a new physician, Dr. George Calvert, had arrived who was acquiring land using his headrights in the Buckroe area of Elizabeth City. Dr. Calvert was called upon to treat Adam. [4] When Adam’s estate was being settled in April 1641, it was noted in the James City Quarter Court that

In 1610, Dr Lawrence Bohune was the first English physician sent to the Virginia Colony. Dr. John Pott was sent to replace him in 1620, but few trained doctors followed in subsequent years. Physician services were so expensive that the General Assembly noted in 1639 the “immoderate and excessive rates and prices exacted by practitioners in physick and chyrurgery.”. Most Virginians tried herbs and remedies on their own, sometimes seeking out a surgeon instead of a physician as they were cheaper, though not as well regarded or trained. Despite their political differences, Gov. John Harvey even asked the English courts to overturn a 1630 Virginia court conviction of Dr. Pott because he was “the only physician in Virginia skilled in epidemical diseases” at the time. In 1639/40 when Adam became ill, Dr. Pott had moved to the area that would become Williamsburg, but a new physician, Dr. George Calvert, had arrived who was acquiring land using his headrights in the Buckroe area of Elizabeth City. Dr. Calvert was called upon to treat Adam. [4] When Adam’s estate was being settled in April 1641, it was noted in the James City Quarter Court that

the estate of Adam Thorowgood, deceased, stands indebted to the estate of George Calvert, physician, in the sum of £ 20:16.6 sterling for physics administered to the sd. Capt. Adam Thorowgood and his servants in the time of their sickness. [5]

The “physics” or treatments would likely have followed the popular theory of Galen’s system of four bodily “humors” with the heat of a fever being thought to be too much hot blood in the system. According to Dr. Sequeyra of early Williamsburg, the diseases of winter and spring were “generally of the Inflammatory kind; require plentiful bleeding…and sometimes blisters.” This, as well as the popular purges, left many patients in a more weakened and dehydrated state which exacerbated the course of diseases. William Harvey, an English physician, challenged that thinking with his 1629 book On the Motion of Heart and Blood, and treatments began to include more chemical and metallic remedies. It is not known if English-trained Dr. Calvert tried any of these new ideas or treatments on Adam. Sadly, Dr. Calvert himself did not survive long in Virginia. [6]

The Burial

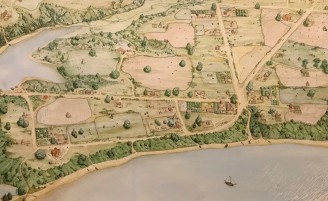

No one is certain whether Adam Thorowgood was treated by Dr. Calvert and died at James City or in Elizabeth City on transit to his home or if he was able to make it back to Lynnhaven before he died. All three of those sites were easily connected by water. Wherever, he had sufficient strength and awareness to prepare a comprehensive will in which he left instructions for his burial: “I bequeath my soul into the hands of my Creator and Redeemer and my body to the earth from which it was taken, to be buried in the Parish Churchyard near my children….” Adam was leaving behind four young children who were very much on his mind in his will, and he would have wanted them to remember him. Some have speculated that Adam might have been referring to unknown buried children. As happened to many settlers, Adam and Sarah likely had other children born to them in their earlier years of marriage who died young, but there is no record of them.

Adam had given land for the Lynnhaven Parish church to be built on the Lynnhaven River near his home. It must have been at least started by the time of his death when he willed “to the Parish Church of Lynnhaven one thousand pounds of tobacco in leaf, to be disbursed for some necessary and decent ornament.” While the lot where that church stood has now been reclaimed by the river, a visitor there in 1819 recorded that the black marble tombstones for Sarah and her second husband John Gookin were still partly above water and readable. However, by 1853, another visitor, William Forrest, noted “the old church has long since fallen to ruins; indeed no vestige remains to mark the identical spot which it occupied …and the old graveyard has also disappeared!” However, he knew of a tall man who had walked out into the river up to his chin and stood on the church gravestones. The first Lynnhaven Church is now memorialized as Church Point in Virginia Beach. There has been discussion of doing underwater archaeology, but nothing has been done yet to explore that site. [7]

“My Dearly Beloved Wife”

While it was common in a will in those times to refer to one’s wife as “beloved,” the conditions of Adam’s will indicate genuine love, respect, and confidence in his wife of just over 12 years. He perceived the feelings to be mutual as he also referred to her as “my loving wife.” He made her not only his sole executrix, but also stated that “she shall have the guardianship of all of my children and their estates, until my daughters come to the age of sixteen years, and my son Adam to the age of one and twenty.” In that era, children were considered orphans when their fathers died, and they were typically appointed male guardians who were relatives or men of standing in the community. With his position and status, there were many Adam could have chosen as suitable guardians for his children, especially for his son who stood to inherit so much, but he unequivocally chose Sarah. In addition to the other bequests Adam had made to her, he added, “and for my wife’s care and pains in bringing up the children in good virtue and training, and likewise for handling and looking after their stocks of cattle, my will and desire is that she shall have all the male increase during the time of their guardianship.” He recognized her efforts as a mother and that his death would increase that burden. The term “cattle” was sometimes used to refer generically to livestock. [8]

Widows were entitled to a portion of their husband’s estate to enjoy during their lifetime. Adam gave Sarah “all the houses and the orchard with the plantation at Lynnhaven… and the ground called by the name of the Quarter during her lifetime.” as well as one of the best sows and calves, a half dozen breeding goats, four breeding sows, and, remarkably, “one mare and one foal, she to take her choice of which she pleaseth…all of which I give her as a memorial of my love.” In accordance with the custom of primogeniture, their only son, Adam II, was to receive “all the rest of his father’s houses and lands in Virginia and elsewhere” when he turned 21 as well as the property willed to his mother after her death. “In Virginia” would have referred to the properties Adam owned in the area of Elizabeth City. “Elsewhere” probably referred to the small land holdings in England Adam had inherited in his father’s will. Adam Thorowgood provided for his daughters Ann, Sarah, and Elizabeth by dividing among his wife, daughters, and son the remaining cows, goats, hogs, mares and horses, servants, crops, and the rest of his estate (excluding his other bequests). Adam and Sarah had at least three enslaved servants at that time, but also had indentured servants under time-limited contracts that would have been passed on. In 1645, his wife Sarah designated Mary as her chosen enslaved servant. [9]

Widows were entitled to a portion of their husband’s estate to enjoy during their lifetime. Adam gave Sarah “all the houses and the orchard with the plantation at Lynnhaven… and the ground called by the name of the Quarter during her lifetime.” as well as one of the best sows and calves, a half dozen breeding goats, four breeding sows, and, remarkably, “one mare and one foal, she to take her choice of which she pleaseth…all of which I give her as a memorial of my love.” In accordance with the custom of primogeniture, their only son, Adam II, was to receive “all the rest of his father’s houses and lands in Virginia and elsewhere” when he turned 21 as well as the property willed to his mother after her death. “In Virginia” would have referred to the properties Adam owned in the area of Elizabeth City. “Elsewhere” probably referred to the small land holdings in England Adam had inherited in his father’s will. Adam Thorowgood provided for his daughters Ann, Sarah, and Elizabeth by dividing among his wife, daughters, and son the remaining cows, goats, hogs, mares and horses, servants, crops, and the rest of his estate (excluding his other bequests). Adam and Sarah had at least three enslaved servants at that time, but also had indentured servants under time-limited contracts that would have been passed on. In 1645, his wife Sarah designated Mary as her chosen enslaved servant. [9]

While there are not exact birthdates for any of their four children, they were all young at the time of Adam’s death. When Sarah Thorowgood Gookin, once again a widow, submitted a letter to the Lower Norfolk Court on July 13, 1647 regarding her children’s inheritances, she indicated none had yet reached majority. Adam II may have been the youngest as he was not 21 when his mother died in 1657, so he requested his brother-in-law (his sister Sarah’s husband) Simon Overzee as his guardian. Thus, daughters Ann, Sarah, and Elizabeth would have been born after 1630 and Adam II after 1636. [10]

Goat Gifts

What would be an appropriate token to show appreciation to those outside one’s immediate family? How about a goat? Living in a tobacco economy with no banks or accounting houses in Virginia to hold cash, the gift of a breeding goat was like giving away stocks today. If one cared properly for the gift, it would increase and bring returns for many years to come. The raising of livestock was profitable in 17th century Virginia. The most common animals to raise were hogs, cows, and goats that could be left to roam and forage for themselves rather than being wholly dependent on cleared pastures and crops raised for their feed. This practice led to some contention between neighbors over damaged gardens, and in 1631-32, a statute was passed requiring landowners to fence in their crops if they wanted them protected from hungry and destructive livestock. It was during that busy 1639/40 Assembly session that the law changed to required settlers to pen in their hogs, but that was later repealed in 1642. [11]

Few sheep were raised in Virginia until the second half of the century when fenced green pastures became more available and wolves somewhat less abundant. However, for many years the most valuable of the animals was the prized, but scarce, horse. In 1649, there were only 300 horses in Virginia. Even as late as 1688, a mare and a foal, such as Sarah received, were worth eight cows. In the Lower Norfolk County area, the numerous streams and rivers served as natural fencing which helped to contain livestock. However, Adam Thorowgood had had both a cow keeper and a goat keeper to look after his animals. In a 1642-43 accounting of Adam’s estate, there were 63 cows and steers, 107 goats, 58 of which were breeders, and 7 horses as well as an undetermined number of hogs. So who got Adam’s goats? [12]

Few sheep were raised in Virginia until the second half of the century when fenced green pastures became more available and wolves somewhat less abundant. However, for many years the most valuable of the animals was the prized, but scarce, horse. In 1649, there were only 300 horses in Virginia. Even as late as 1688, a mare and a foal, such as Sarah received, were worth eight cows. In the Lower Norfolk County area, the numerous streams and rivers served as natural fencing which helped to contain livestock. However, Adam Thorowgood had had both a cow keeper and a goat keeper to look after his animals. In a 1642-43 accounting of Adam’s estate, there were 63 cows and steers, 107 goats, 58 of which were breeders, and 7 horses as well as an undetermined number of hogs. So who got Adam’s goats? [12]

Edward Windham

In his will, Adam Thorowgood referred to Edward as his “well beloved brother,” but used the term “brother” in a broader kinship relationship. Edward was actually the brother of his sister-in-law, Ann Wyndham, who had married his older brother Rev. Thomas Thorowgood. Adam had brought Edward to Virginia as a headright in 1634, and by 1637, Edward was serving as a justice with Adam in the Lower Norfolk Court. He also served as a Burgess. Edward received a cow calf and a breeding goat. [13]

Robert Hayes

“My brother, Robert Hayes,” was actually Adam’s brother-in-law who had married Sarah’s older widowed sister Ann Offley Workman. At age 44 in 1637, Robert claimed a certificate for the transportation of eight people to the Colony, consisting of him and his wife; Amos, Mary, Thomas, and John Wortman/ Workman; and Alexander and Nathaniel Hayes. Robert purchased land around Little Creek in Lower Norfolk, represented Lower Norfolk as a Burgess in the Assembly, and was a vestryman for the Lynnhaven Parish. This Robert Hayes was not the son Robert of Sir Thomas Hayes, a Lord Mayor, but may have been kin as Sir Thomas moved in many of the same merchant circles as the Offleys. Adam willed a breeding goat to Robert and one “to each of Robert Hayes’ three sons.” Ann Hayes who survived her husband Robert by a few months, mentioned four sons, Nathaniel and Adam Hayes and Thomas and John Workman, in her 1650 will, leaving one to wonder which one did not get one of Adam’s goats and why. Amos Workman signed the codicil to Ann’s will, but his relationship to Ann Hayes was not explained. [14]

Adam Keeling

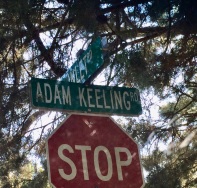

The entry “To my godson, Adam Keeling, one breeding goat,” explicitly stated Adam K.’s relationship to Adam T. who was his godfather and namesake. Thomas Keeling, Adam K.’s father, had been been brought to Virginia as a headright by Adam Thorowgood in 1628 aboard the Hopewell. In 1634, Thomas himself transported four headrights to the Colony, including his wife Anne. In 1637, he was an agent for Adam Thorowgood, and in 1640 he was appointed a vestryman for the parish. Thomas became an Ensign and then a Lieutenant in the militia. He acquired property across the Lynnhaven River from the Thorowgoods, and their descendants were neighbors and friends for many years. Like the later brick Thoroughgood House, there is a privately-owned brick ancestral home of the Keelings from that same era that gained the name “Ye Dudleys.” When Thomas died, Ann Keeling married Robert Bray. [15]

The entry “To my godson, Adam Keeling, one breeding goat,” explicitly stated Adam K.’s relationship to Adam T. who was his godfather and namesake. Thomas Keeling, Adam K.’s father, had been been brought to Virginia as a headright by Adam Thorowgood in 1628 aboard the Hopewell. In 1634, Thomas himself transported four headrights to the Colony, including his wife Anne. In 1637, he was an agent for Adam Thorowgood, and in 1640 he was appointed a vestryman for the parish. Thomas became an Ensign and then a Lieutenant in the militia. He acquired property across the Lynnhaven River from the Thorowgoods, and their descendants were neighbors and friends for many years. Like the later brick Thoroughgood House, there is a privately-owned brick ancestral home of the Keelings from that same era that gained the name “Ye Dudleys.” When Thomas died, Ann Keeling married Robert Bray. [15]

Because of the many close connections between those two families, some online family trees have claimed that Thomas’s wife was an Anne Thorowgood and the sister or niece of Adam Thorowgood. However, Adam’s only sister was Frances who married and stayed in England. Neither was Ann Keeling the daughter of his brother Sir John Thorowgood of Kensington as has also been suggested, because Sir John had no surviving descendants as confirmed in his will. If she were a Thorowgood, there were multiple other families of that name in England. However, no 17th century documents have been provided by those making the claim to verify Ann’s maiden name or ancestry. If Anne Keeling had been a relative, Adam Thorowgood surely would have acknowledged that relationship in his will as he did with Windham and Hayes. [16]

Jane Wheeler and William Stephens

Jane Wheeler and William Stephens each received both a breeding goat and a shoat (young pig). However, there are no records of any connection they had to Adam Thorowgood. Neither Jane nor William appear in court or land records with the Thorowgoods or their associates nor were they prominent in the Colony. Ann Hayes included a kinswoman named Jane Needham in her will, which might lead one to speculate a re-marriage or transcription error, but Adam Thorowgood gave no relationship to this Jane. Perhaps Jane Wheeler and William Stephens had rendered special services or assisted in the time of Adam’s illness. Whatever, they were both recipients of a generous gift. [17]

Jane Wheeler and William Stephens each received both a breeding goat and a shoat (young pig). However, there are no records of any connection they had to Adam Thorowgood. Neither Jane nor William appear in court or land records with the Thorowgoods or their associates nor were they prominent in the Colony. Ann Hayes included a kinswoman named Jane Needham in her will, which might lead one to speculate a re-marriage or transcription error, but Adam Thorowgood gave no relationship to this Jane. Perhaps Jane Wheeler and William Stephens had rendered special services or assisted in the time of Adam’s illness. Whatever, they were both recipients of a generous gift. [17]

Overseers of the Will

In that era, overseers were sometimes appointed to assist and supervise the work of the executor of a will. To assist with the Virginia affairs, Adam Thorowgood selected his “well beloved friends” Capt. Thomas Willoughby and Henry Seawell who both served as justices at the Lower Norfolk Court like Adam. However, sometimes one can be wrong on how “beloved” friends might be. After Adam’s death, both declined to serve in that capacity without explanation, so it is not known if they did not have the time, did not want to be entangled in Adam’s affairs, did not want to work with his wife Sarah, were encouraged to withdraw by Sarah, or thought everything was in order. Adam had planned that each overseer would receive a gold ring of 20 schillings value as “a pledge of my love,” which hopefully they did not accept as they did not do the work. [18]

For the English affairs, Adam appointed his “dearly beloved brother Sir John Thorowgood of Kensington” and Mr. Alexander Harris whom Adam identified as his wife’s uncle living on Tower Hill. It was logical that Adam would rely on his brother Sir John who was a Gentleman of the Bed Chamber of Charles I and with whom Adam had been involved with tobacco shipments. However, the identity and involvement of Mr. Alexander Harris is a mystery. Sarah did not have an “Uncle Alexander,” and there is no Harris to be found in the extensive official Offley Pedigree or known of in the Osbourne line. Even if Harris were extended kin to Sarah Offley Thorowgood, she had several wealthy and influential brothers living in London who could have handled any claims. Perhaps, Harris worked for or with one of her uncles. In that era, Tower Hill was still the main place for executions, but, according to the London tithable list for 1638, Alexander Harris was one of the wealthy living there amongst the almshouses, foundry, small shops, and housing for foreigners. Was he the Alexander Harris who was the former warden of Fleet Prison or the one involved with shipping to Virginia? How Adam connected to Alexander is still a puzzle. [19]

For the English affairs, Adam appointed his “dearly beloved brother Sir John Thorowgood of Kensington” and Mr. Alexander Harris whom Adam identified as his wife’s uncle living on Tower Hill. It was logical that Adam would rely on his brother Sir John who was a Gentleman of the Bed Chamber of Charles I and with whom Adam had been involved with tobacco shipments. However, the identity and involvement of Mr. Alexander Harris is a mystery. Sarah did not have an “Uncle Alexander,” and there is no Harris to be found in the extensive official Offley Pedigree or known of in the Osbourne line. Even if Harris were extended kin to Sarah Offley Thorowgood, she had several wealthy and influential brothers living in London who could have handled any claims. Perhaps, Harris worked for or with one of her uncles. In that era, Tower Hill was still the main place for executions, but, according to the London tithable list for 1638, Alexander Harris was one of the wealthy living there amongst the almshouses, foundry, small shops, and housing for foreigners. Was he the Alexander Harris who was the former warden of Fleet Prison or the one involved with shipping to Virginia? How Adam connected to Alexander is still a puzzle. [19]

Adam’s older brother Sir John Thorowgood of Kensington was not all that some have claimed. Fortunately, Adam used the designation “of Kensington'” because there were two Sir John Thorowgoods in London at the time. Unfortunately, their identities were merged in mid-19th century publications in America, and many historians and genealogists have since perpetuated the claim that Adam’s brother had been a secretary for the Earl of Pembroke who had close ties to the Virginia Company. However, Pembroke’s secretary was Sir John Thorowgood of Charing Cross who served as a Minister of Parliament. Likewise, the 17th century portrait of “Sir John Thorowgood” often seen today is most likely of this other Sir John. Adam’s brother was never in Parliament, but remarkably managed to go from the court of Charles I to a responsible trustee position in the Interregnum government back to an honored position in the court of Charles II in the Restoration. More relevant to this post, though, Sir John lived comfortably in England to the age of 80. Adam achieved success, but the New World adventurer was dead at 36.

Special thanks to Jorja Jean for sharing her insights and research.

Next Post: Sarah Offley Thorowgood Gookin Yeardley, A Formidable Woman of the 17th Century

Footnotes

[1] “The Thorowgood Family of Princess Anne County, Va, ” The Richmond Standard, 4:13 (26 November 1881). Dorman, John Frederick, Adventurers of Purse and Person, Volume Three Families R-Z, 4th ed. (Baltimore:Genealogical Publishing Co., 2007), 326-328. Turner, Florence Kimberly, Gateway to the New World: A History of Princess Anne County, Virginia, 1607-1824 (Easley, South Carolina: Southern Historical Press, 1984), 37-38.

[2] Walter, Alice Granbery, Lower Norfolk County, Virginia, Court Records : Book “A,” 1637-1646 (Baltimore: Clearfield, 2009), 20. Hening, William Waller, The Statutes at Large Being a Collection of all the Laws of Virginia from the First Session of the Legislature in the Year 1619, vol. I (New York: R.W. & G. Bartow, 1823), 254. Accessed online at books. google on 10/5/2021.

[3] Gill, Harold B,, Jr., “Dr. Sequeyra’s ‘Diseases of Virginia,'” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, 86:3 (July 1978), 296-297. Mires, Peter B., “Contact and Contagion: The Roanoke Colony and Influenza,” Historical Archaeology, 28:3 (1994) 30-38. Accessed online through JSTOR 25616316. on 9/28/2021. Savitt, Todd L., Fevers, Agues, and Cures: Medical Life in Old Virginia (Richmond: Virginia Historical Society, 1990), 21-24.

[4] Savitt, 29-30. Ehrhardt, John D., Jr., and Patrick O’Leary, “The Rise of the Surgeon in the Seventeenth Century Virginia Colony,” American Surgery, 84:6 (Jun 1, 2018), 763-765. Accessed online at the National Library of Medicine at PubMed.gov on 10/1/21. Magruder, Caleb Clarke, Jr., “American Medical Biographies/Pott, John,” Interstate Medical Journal, 17 (St. Louis 1910), 126-128. Accessed 10/9/21 at wikisource.org. Nugent, Nell Marion. Cavaliers and Pioneers: Abstracts of Virginia Land Patents and Grants, 1623-1800 (Richmond: Dietz Printing Co., 1934), 135, 146, 157.

[5] Turner, 37. “The Thorowgood Family,” The Richmond Standard.

[6] Gill, 296-7. Savitt, 12-14, 29-30.

[7]”The Thorowgood Family,” The Richmond Standard. Forrest, William S. Historical and Descriptive Sketches in Norfolk and Vicinity (Philadelphia: Lindsay and Blakiston, 1853), 459-460. Mansfield, Stephen S., Princess Anne County and Virginia Beach: A Pictorial History (Norfolk: The Donning Company, 1989), 12. Turner, 17.

[8]”The Thorowgood Family,” The Richmond Standard.

[9] Walter, Book A, 176. “The Thorowgood Family,” The Richmond Standard. Brayton, John Anderson, “The Ancestry of Mrs. Anne (Thoroughgood) Chandler-Fowke,” The Virginia Genealogist, 48:4 (October-December 2004), 246-249.

[10] Walter, Alice Granbery, Lower Norfolk County, Virginia, Court Records : Book “B,” 1646-1651/2 (Baltimore: Clearfield, 2009), 48. Brayton, John A., Transcription of Lower Norfolk County, Virginia Records, Volume One: Wills and Deeds, Book D 1656-1666 (Jackson, Mississippi: Cain Lithographers, Inc., 2007), 190. Dorman, 328-333.

[11] Hening, 228. Bruce, Philip Alexander, Economic History of Virginia in the Seventeenth Century, Volume 1, (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1907), 314-316. Horn, James, Adapting to a New World, (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1994), 777-778.

[12] Bruce, 298-299, 334-336, 373-374. Walter, Book A, 120, 150-151, 178.

[13] Walter, Book A, 1-2. McCartney, Martha W., Jamestown People to 1800 (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company, 2012), 452. “The Thorowgood Family,” The Richmond Standard.

[14] Walter, Book A, 3,6,137. McCartney, 200. Turner, 41. “The Thorowgood Family,” The Richmond Standard.

[15] Kellam, Sadie Scott and V. Hope Kellam, Old Houses in Princess Anne Virginia (Portsmouth, VA: Printcraft Press, 1931), 56-59. Turner, 48-50. Walter, Book A, 1, 3, 40.

[16] Brayton, 246-249. Matthew, H. C. G., and Brian Harrison ed., “Thoroughgood, John” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 54 (London: Oxford University Press, 2004), 660-662. Will of Sir John Thorowgood of Kensington, 1675, Catalogue Reference Prob /11/349, Public Records Office: The National Archives (UK).

[17] “The Thorowgood Family,” The Richmond Standard. Walter, Book B, 137

[18] “The Thorowgood Family,” The Richmond Standard. Turner, 51.

[19] Bower, G.C. and H.W.F. Harwood, “Pedigree of Offley,” The Genealogist: A Quarterly Magazine of Genealogical, Antiquarian, Topographical, and Heraldic Research, XIX, 1903, 217-231. Garner-Biggs Bulletin, 30:1, self published. Clayton, Rev. P.B. and B.R. Leftwich, The Pageant of Tower Hill (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1933), 128, 133, 147-148. Harris, Alexander, The oeconomy of the Fleeete, of An Apologeticall Answere of Alexander Harris (late warden there) unto XIX Articles set forth against him by the prisoners, Augustus Jessopp, ed., (London: Camden Society, 1879).

[20] Will of Sir John. Matthew, 660-662. Thrush, Andrew and John P. Ferris, ed., Thorowgood, John (1588-1657), of Brewer’s Lane, Charing Cross, Westminster; later of Billingbear, Berks. and Clerkenwell, Mdx. accessed 7/7/2018 at history of parliament online.

The tobacco cycle impacted the schedule of ships arriving from and returning to England. Planters worried whether their hogsheads would make it safely across the ocean and then whether English merchants would give them a fair price. Tobacco credit notes became the very currency for purchases and payments in the colony, but one’s profits depended on a fluctuating English market. Neither Thorowgood nor Thomson could afford to lose a shipment.

The tobacco cycle impacted the schedule of ships arriving from and returning to England. Planters worried whether their hogsheads would make it safely across the ocean and then whether English merchants would give them a fair price. Tobacco credit notes became the very currency for purchases and payments in the colony, but one’s profits depended on a fluctuating English market. Neither Thorowgood nor Thomson could afford to lose a shipment. In the 16th century the great English trading companies opened trade markets for exporting English goods and importing needed and exotic wares. Most notable were the Merchant Adventurers; the Muscovy Company for Russia; the

In the 16th century the great English trading companies opened trade markets for exporting English goods and importing needed and exotic wares. Most notable were the Merchant Adventurers; the Muscovy Company for Russia; the

The headright system that had been established to encourage English men and women to come to Virginia as indentured servants worked relatively well for immigrants and investors in the second quarter of the 17th century. However, one of the problems was that even when indentured servants managed to survive 4-7 years in Virginia, the planter had to find a replacement when the time was over, unless they entered into a tenancy arrangement. A successful landowner had to deal with constant turnover. Virginia had an insatiable need for workers. (See

The headright system that had been established to encourage English men and women to come to Virginia as indentured servants worked relatively well for immigrants and investors in the second quarter of the 17th century. However, one of the problems was that even when indentured servants managed to survive 4-7 years in Virginia, the planter had to find a replacement when the time was over, unless they entered into a tenancy arrangement. A successful landowner had to deal with constant turnover. Virginia had an insatiable need for workers. (See

In contrast, the sessions in 1631-32 were groundbreaking as the Assembly decided to review, consolidate, revise, void when needed, and reform the body of laws that had accumulated over the years. This was their first attempt to develop and publish a consistent Code of Law for the Colony. The first review appeared to have taken place by only a partial Assembly as it included only 20 Burgesses representing 13 combined districts and started meeting on February 21, 1631/32. They produced a document of 68 acts which included 15 related to Church matters. Not surprisingly, the “urine collection” regulation did not survive the review.

In contrast, the sessions in 1631-32 were groundbreaking as the Assembly decided to review, consolidate, revise, void when needed, and reform the body of laws that had accumulated over the years. This was their first attempt to develop and publish a consistent Code of Law for the Colony. The first review appeared to have taken place by only a partial Assembly as it included only 20 Burgesses representing 13 combined districts and started meeting on February 21, 1631/32. They produced a document of 68 acts which included 15 related to Church matters. Not surprisingly, the “urine collection” regulation did not survive the review.  This was my puzzlement–the curiosity that started my research and blog. How did a twenty-two-year-old young man raised in Norfolk, England, having just spent four years working as an indentured servant in Virginia, suddenly show up in London and, within a year, marry the daughter of a wealthy merchant who was also a granddaughter and great-granddaughter of Lord Mayors of London? In the Big Bang Theory of life, how did these two very different orbits ever come crashing into each other? The marriage of Adam Thorowgood to Sarah Offly was recorded in the parish register of St. Anne’s Blackfriars, London, on July 18, 1627.

This was my puzzlement–the curiosity that started my research and blog. How did a twenty-two-year-old young man raised in Norfolk, England, having just spent four years working as an indentured servant in Virginia, suddenly show up in London and, within a year, marry the daughter of a wealthy merchant who was also a granddaughter and great-granddaughter of Lord Mayors of London? In the Big Bang Theory of life, how did these two very different orbits ever come crashing into each other? The marriage of Adam Thorowgood to Sarah Offly was recorded in the parish register of St. Anne’s Blackfriars, London, on July 18, 1627.

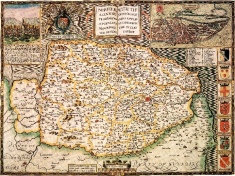

William Thorowgood was born around 1560 in Felsted, Essex, but moved to Grimston, Norfolk around 1585 when he married Anne Edwards of Norwich, Norfolk, and accepted the post as the Vicar of St. Boltolph’s Church. All of William’s nine children were born in Grimston. Reverend Thorowgood was honored by being appointed as the commissary for the Bishop of Norwich. William came from an armorial family. Although not needed for his position with the church, he received “a confirmation of this Armes and Crest” in March 1620.

William Thorowgood was born around 1560 in Felsted, Essex, but moved to Grimston, Norfolk around 1585 when he married Anne Edwards of Norwich, Norfolk, and accepted the post as the Vicar of St. Boltolph’s Church. All of William’s nine children were born in Grimston. Reverend Thorowgood was honored by being appointed as the commissary for the Bishop of Norwich. William came from an armorial family. Although not needed for his position with the church, he received “a confirmation of this Armes and Crest” in March 1620.  Robert Offley II and his wife, Anne Osbourne, were both born in London. Robert was a “Turkey merchant” with the Levant Company (traders with the Ottomans) whose first Governor was his father-in-law, Sir Edward Osborne. Osborne had been knighted and had been a Lord Mayor of London (like his father-in -law William Hewitt).

Robert Offley II and his wife, Anne Osbourne, were both born in London. Robert was a “Turkey merchant” with the Levant Company (traders with the Ottomans) whose first Governor was his father-in-law, Sir Edward Osborne. Osborne had been knighted and had been a Lord Mayor of London (like his father-in -law William Hewitt).  It has sometimes been assumed that Adam’s older brother, Sir John Thorowgood of Kensington, brought the families together based on his position in the court of King Charles I and the erroneous belief that he had been serving as the secretary to William Herbert, Earl of Pembroke, a significant member of the Virginia Company of London. As

It has sometimes been assumed that Adam’s older brother, Sir John Thorowgood of Kensington, brought the families together based on his position in the court of King Charles I and the erroneous belief that he had been serving as the secretary to William Herbert, Earl of Pembroke, a significant member of the Virginia Company of London. As

Sarah and her sisters might have been even more daring than her brothers. They likely had watched with interest as the Virginia Company had recruited “young, handsome, and honestly-educated Maids” to send to the Colony in 1620-21 on “bride ships” to establish families and bring greater stability and order to colonial society. These women were as much “adventurers” as their male counterparts.

Sarah and her sisters might have been even more daring than her brothers. They likely had watched with interest as the Virginia Company had recruited “young, handsome, and honestly-educated Maids” to send to the Colony in 1620-21 on “bride ships” to establish families and bring greater stability and order to colonial society. These women were as much “adventurers” as their male counterparts.

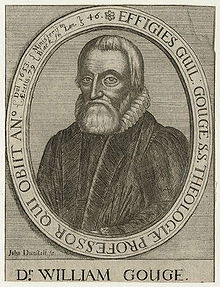

Sarah and Adam would certainly have been familiar with Reverend William Gouge’s famous sermon “Of Domestical Duties” delivered there in 1622 which was considered a “text” on family life in that era. In the hierarchical structure popular in that age, Reverend Gouge saw a wife as above her children, but below her husband who was to be “as a Priest unto his wife…. He is as a king in his owne house.”

Sarah and Adam would certainly have been familiar with Reverend William Gouge’s famous sermon “Of Domestical Duties” delivered there in 1622 which was considered a “text” on family life in that era. In the hierarchical structure popular in that age, Reverend Gouge saw a wife as above her children, but below her husband who was to be “as a Priest unto his wife…. He is as a king in his owne house.”

However, in 1623, accusations of mismanagement fueled by the report “Unmasked Face of our Colony in Virginia as it was in the Winter of the Year 1622” by Nathaniel Butler (a Governor of Bermuda who had only briefly visited Virginia), led to an investigation by the King’s Privy Council. That had been a particularly difficult year for the Colony with the unanticipated Powhatan Uprising, and there were deep divisions in the Company. Sir Edwin Sandys who controlled the company at that time had been an outspoken critic of the King. Despite lengthy protests and rebuttals by the Virginia Governor and Councilors, the Crown dissolved the Virginia Company and made Virginia a Royal Colony on May 24, 1624. This was a hostile “take-over,” not a “buyout,” of the investors who had initially provided the capital and absorbed all the risk. In the Company’s dying gasp in 1625, Governor Wyatt protested: “…the business of Virginia, so foiled and wronged by the party opposite and now reduced to extreme terms…wherein our former labors, cares, and expenses had received … the undeserved reward of rebuke and disgrace.”

However, in 1623, accusations of mismanagement fueled by the report “Unmasked Face of our Colony in Virginia as it was in the Winter of the Year 1622” by Nathaniel Butler (a Governor of Bermuda who had only briefly visited Virginia), led to an investigation by the King’s Privy Council. That had been a particularly difficult year for the Colony with the unanticipated Powhatan Uprising, and there were deep divisions in the Company. Sir Edwin Sandys who controlled the company at that time had been an outspoken critic of the King. Despite lengthy protests and rebuttals by the Virginia Governor and Councilors, the Crown dissolved the Virginia Company and made Virginia a Royal Colony on May 24, 1624. This was a hostile “take-over,” not a “buyout,” of the investors who had initially provided the capital and absorbed all the risk. In the Company’s dying gasp in 1625, Governor Wyatt protested: “…the business of Virginia, so foiled and wronged by the party opposite and now reduced to extreme terms…wherein our former labors, cares, and expenses had received … the undeserved reward of rebuke and disgrace.”

There were around 40 major outbreaks of plague in London over the next three hundred years, occurring approximately e

There were around 40 major outbreaks of plague in London over the next three hundred years, occurring approximately e

Unfortunately, it was not just church bells in London that tolled in mourning that year. Without adequate finances, planning, preparation, provisions, or training of its troops, England agreed to join the fight with the Dutch (Protestant) Republic to lift the siege of the City of Breda by the (Catholic) Army of Flanders/ Hapsburg. When the lengthy siege finally ended and the Dutch were forced to sign articles of capitulation on June 2, 1625, fewer than 600 of the 7,000 (less than 9%) of the English troops had survived. Rather than blaming the commander Mansfield, most put the blame on the Duke of Buckingham “whose military enthusiasm did not include attention to the details of policy or planning.”

Unfortunately, it was not just church bells in London that tolled in mourning that year. Without adequate finances, planning, preparation, provisions, or training of its troops, England agreed to join the fight with the Dutch (Protestant) Republic to lift the siege of the City of Breda by the (Catholic) Army of Flanders/ Hapsburg. When the lengthy siege finally ended and the Dutch were forced to sign articles of capitulation on June 2, 1625, fewer than 600 of the 7,000 (less than 9%) of the English troops had survived. Rather than blaming the commander Mansfield, most put the blame on the Duke of Buckingham “whose military enthusiasm did not include attention to the details of policy or planning.”

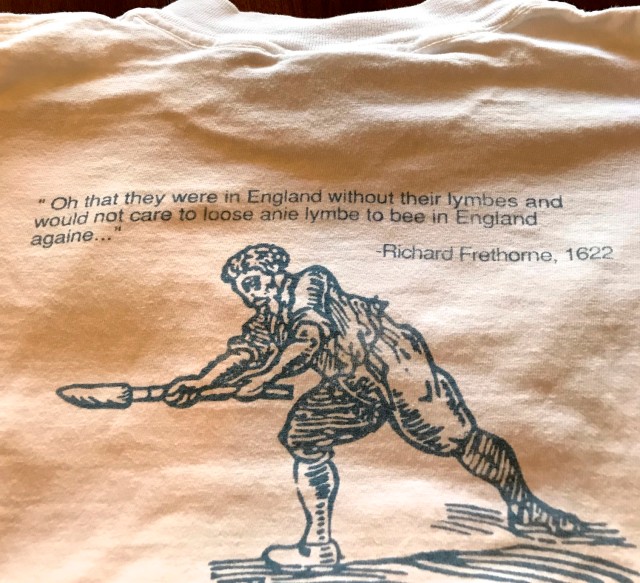

Indentureships were usually pre-arranged through a contract with set terms signed before the voyage between the potential servant and the ship’s captain or a merchant paying for the voyage. Usual terms were for 4-5 years, but it could be more for younger servants. Those contracts would then be sold to the planters when the ship arrived. Persons who arrived without a prior contract, but who wanted to be in service, might find their terms longer or less desirable, as their services were sold in the “custom of the country.” I will focus on Virginia in this post, but indentured servants were also heading to the West Indies, Barbados, Ireland, and other British colonies.

Indentureships were usually pre-arranged through a contract with set terms signed before the voyage between the potential servant and the ship’s captain or a merchant paying for the voyage. Usual terms were for 4-5 years, but it could be more for younger servants. Those contracts would then be sold to the planters when the ship arrived. Persons who arrived without a prior contract, but who wanted to be in service, might find their terms longer or less desirable, as their services were sold in the “custom of the country.” I will focus on Virginia in this post, but indentured servants were also heading to the West Indies, Barbados, Ireland, and other British colonies.

What seemed to make the difference between those who survived and those who did not? Among indentured servants, older ones with some education, skills, and/or connections fared better. Outcomes were surely affected as well by individual personalities, self- advocacy skills, and work ethics. Potential servants might have been able to choose a broad destination (Virginia v. West Indies),and those who sought advice and input in advance may have fared better.

What seemed to make the difference between those who survived and those who did not? Among indentured servants, older ones with some education, skills, and/or connections fared better. Outcomes were surely affected as well by individual personalities, self- advocacy skills, and work ethics. Potential servants might have been able to choose a broad destination (Virginia v. West Indies),and those who sought advice and input in advance may have fared better.

with his former indentured servant, Adam Thorowgood. Once again, Adam had been fortunate.

with his former indentured servant, Adam Thorowgood. Once again, Adam had been fortunate.

Adam Thorowgood and Sarah Offley had only four children who lived to maturity: Ann, Sarah (who had no surviving children), Elizabeth, and Adam II. When Adam, their immigrant father, died at the age of 36 in 1640, his will specifically named these children and stated that they were all minors. According to a letter written to the Lower Norfolk County Court in 1647 by his remarried widow, Sarah Thorowgood Gookin, they were still minors seven years later. In his will, Adam had said that the daughters would come of age at 16 and his son at 21. As Adam II selected a guardian at the death of his mother in 1657, he clearly had not yet reached majority.

Adam Thorowgood and Sarah Offley had only four children who lived to maturity: Ann, Sarah (who had no surviving children), Elizabeth, and Adam II. When Adam, their immigrant father, died at the age of 36 in 1640, his will specifically named these children and stated that they were all minors. According to a letter written to the Lower Norfolk County Court in 1647 by his remarried widow, Sarah Thorowgood Gookin, they were still minors seven years later. In his will, Adam had said that the daughters would come of age at 16 and his son at 21. As Adam II selected a guardian at the death of his mother in 1657, he clearly had not yet reached majority. Thorowgoods at the time of Charles I. Unfortunately, their stories have become entangled, impacting assumptions regarding Adam. The “of Kensington” seems to be the distinguishing designation between Adam’s brother who served in the courts of Charles I and Charles II and the other Sir John Thorowgood who was the secretary to the Earl of Pembroke and was put forward by that Earl to become a Minister of Parliament.

Thorowgoods at the time of Charles I. Unfortunately, their stories have become entangled, impacting assumptions regarding Adam. The “of Kensington” seems to be the distinguishing designation between Adam’s brother who served in the courts of Charles I and Charles II and the other Sir John Thorowgood who was the secretary to the Earl of Pembroke and was put forward by that Earl to become a Minister of Parliament.

05-1913 and in articles in The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography starting in 1893.

05-1913 and in articles in The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography starting in 1893.

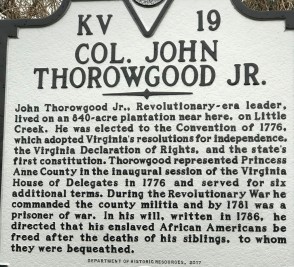

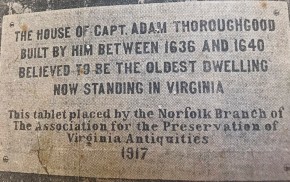

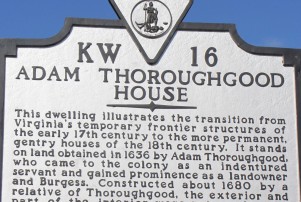

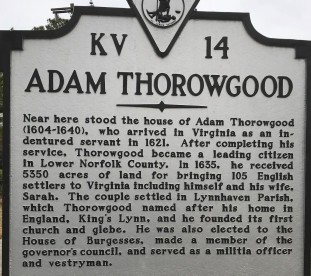

Recently, though, there has been a return to the original spelling. In 2006, a Virginia State Highway marker was added in Virginia Beach for Adam Tho

Recently, though, there has been a return to the original spelling. In 2006, a Virginia State Highway marker was added in Virginia Beach for Adam Tho