It is common to assume the inevitability of history. After all, the story usually favors the victor. Was it really North America’s manifest destiny to be English? In the middle of the 17th century, it appeared North America could have become multi-national like Europe. Not everyone accepted that the establishment of the English colony at Jamestown, already hemmed in by the French in Canada and the Spanish in Florida, created an English claim to all the Eastern seaboard in between.

It is common to assume the inevitability of history. After all, the story usually favors the victor. Was it really North America’s manifest destiny to be English? In the middle of the 17th century, it appeared North America could have become multi-national like Europe. Not everyone accepted that the establishment of the English colony at Jamestown, already hemmed in by the French in Canada and the Spanish in Florida, created an English claim to all the Eastern seaboard in between.

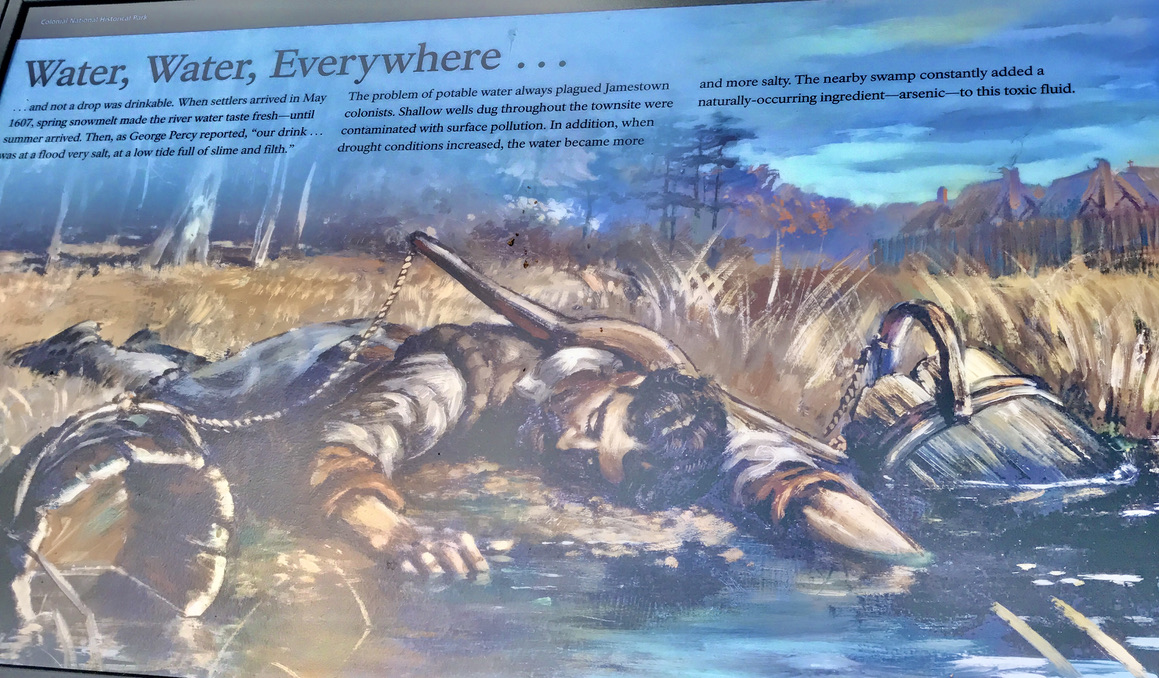

In 1609 when Jamestown was facing its Starving Time, Henry Hudson, an English explorer, accepted a commission from merchants of the Dutch East India Company of the Netherlands (which was in competition with the English East India Company) to find a northern sea route to the East Indies. On this journey, Hudson, finding the route across the Arctic still blocked with ice in May, turned his ship Halve Maeri (Half Moon) around and decided to look for a route through North America. Though not the first to find the “North River” (later renamed the Hudson River in his honor), his exploration went as far as present-day Albany. This became the basis of Dutch claims and the settlement of New Netherlands in what is now New York and New Jersey. Capt. Hudson journeyed as far south as the tip of the Chesapeake Penninsula. The following year, Hudson led an English expedition where he claimed Hudson Bay to the north for the English, after which he was set adrift by his own mutinous crew with his teenage son and 7 loyal crewmen in James Bay, never to be heard of again. [1]

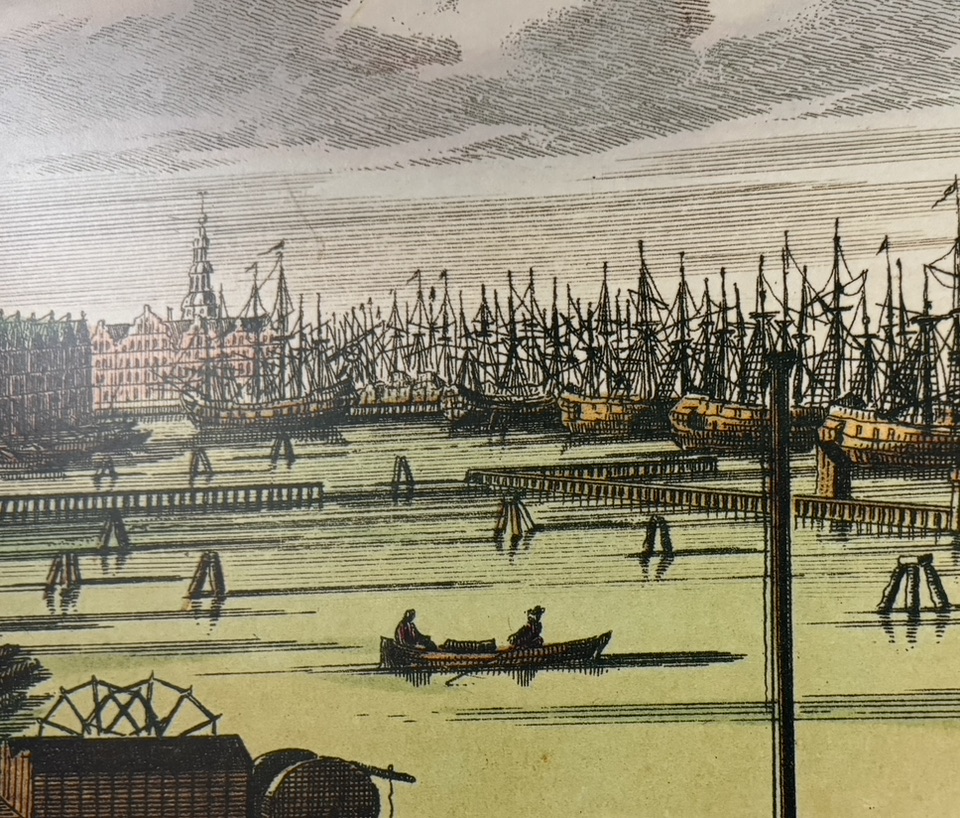

The Dutch settled New Netherlands by 1623 and founded their key city New Amsterdam (Manhattan) in 1626. Much of the wealth of the colony came from lucrative fur trading through alliances with the local indigenous tribes. Like its European namesake, New Amsterdam quickly drew settlers from a variety of countries. Alongside the Dutch lived French-speaking Huguenots, Scandinavians, Germans, and English. The Dutch were heavily involved in the slave trade, so Africans were unwillingly also part of their communities. [2]

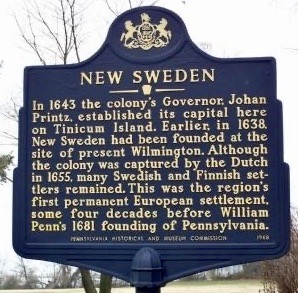

Nor were the Dutch the only Europeans settling the mid-Atlantic. Sweden, a rising European power, authorized the New Sweden Company and enticed Peter Minuit, a former governor of New Netherlands who was unhappy about his recall to Holland, to lead their first expedition to North America. They purchased land from the local Lenape chiefs and established Fort Christina in the area of today’s Wilmington, Delaware. In Anglo-centric history, William Penn is credited with founding Pennsylvania in 1681, but the Swedes were there by 1640 and had a thriving community outside today’s Philadelphia. Although there were bickering claims over the Delaware River Valley between the Dutch and Swedes, they combined forces in 1641-42 to drive out a group of English settlers trying to establish their claim there. Ultimately, the Dutch under their governor/ general Peter Stuyvesant attacked and conquered New Sweden in 1655. [3]

Nor were the Dutch the only Europeans settling the mid-Atlantic. Sweden, a rising European power, authorized the New Sweden Company and enticed Peter Minuit, a former governor of New Netherlands who was unhappy about his recall to Holland, to lead their first expedition to North America. They purchased land from the local Lenape chiefs and established Fort Christina in the area of today’s Wilmington, Delaware. In Anglo-centric history, William Penn is credited with founding Pennsylvania in 1681, but the Swedes were there by 1640 and had a thriving community outside today’s Philadelphia. Although there were bickering claims over the Delaware River Valley between the Dutch and Swedes, they combined forces in 1641-42 to drive out a group of English settlers trying to establish their claim there. Ultimately, the Dutch under their governor/ general Peter Stuyvesant attacked and conquered New Sweden in 1655. [3]

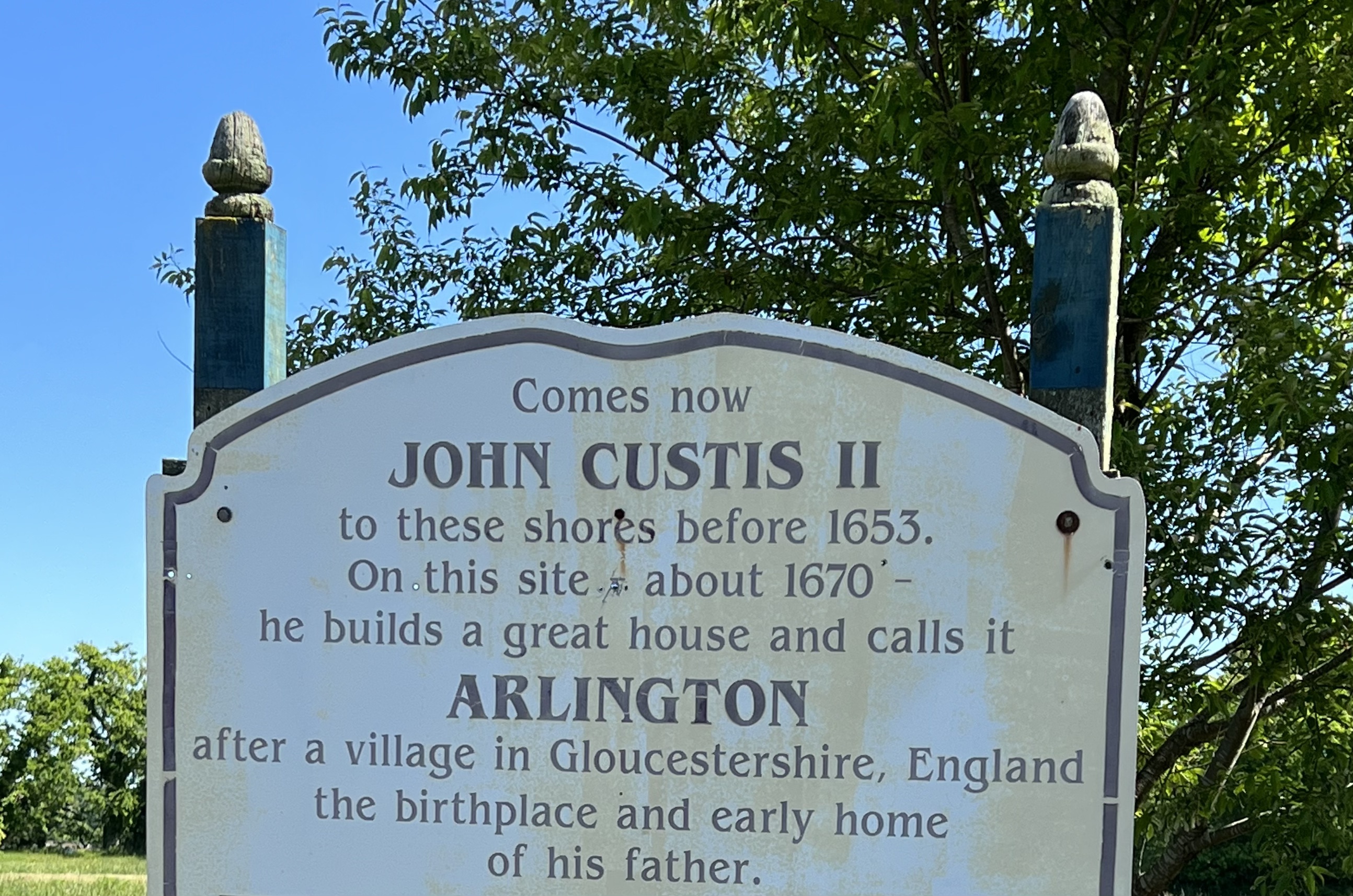

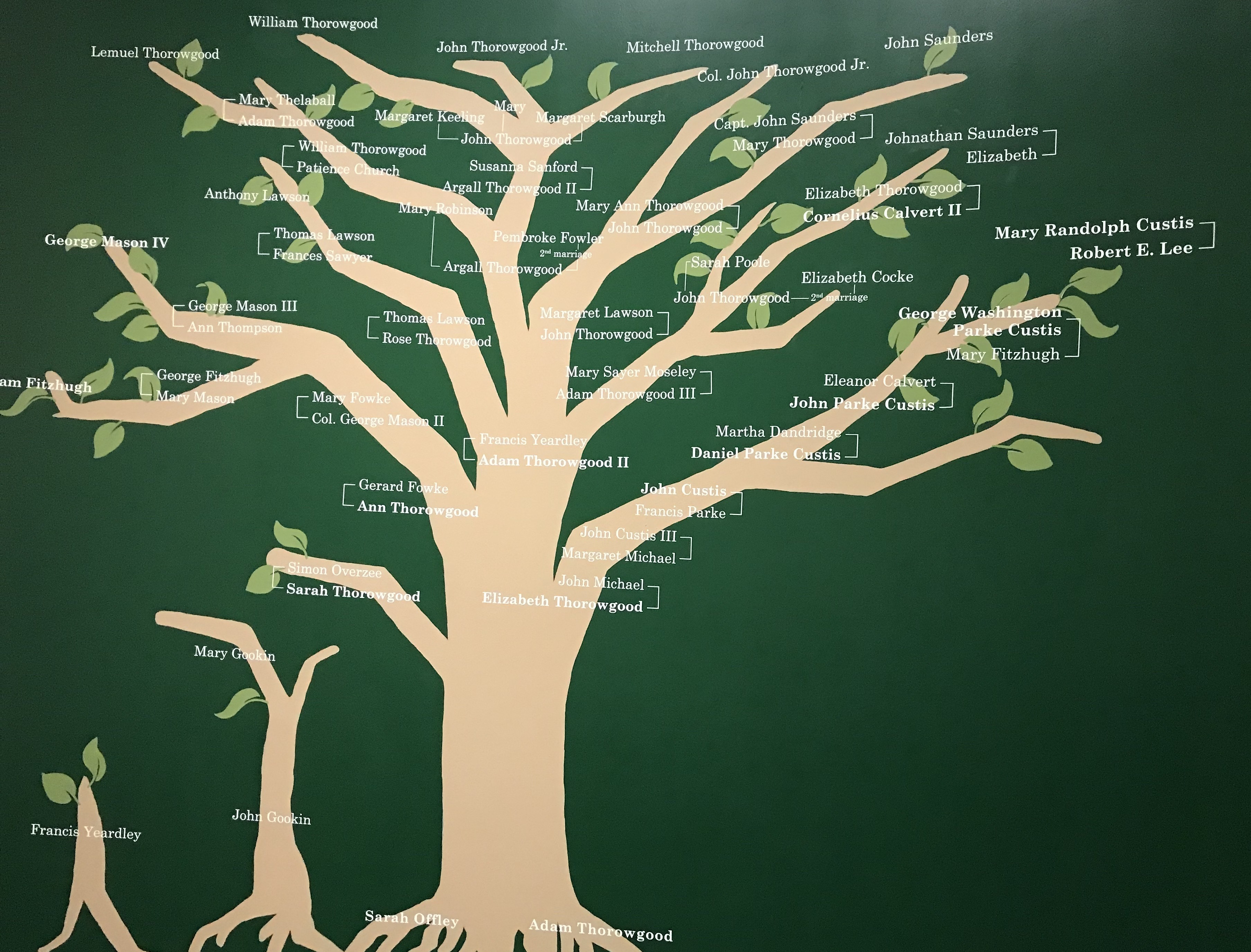

So what does this history have to do with my meandering story of the Thorowgoods in Virginia and their connections? First, one must grapple with the term “Dutch merchant.” Should that term be restricted to someone born of Dutch parents in the Netherlands who was engaged in trading goods in Dutch ships? Could it include those ex-patriots, born in England, but who migrated to the Netherlands to do business through Dutch or even English companies? What about those, like John Custis II, who were born in the Netherlands to English parents? Although John Custis II arrived in Virginia about 1651, he had to wait until 1658 before he was naturalized by an Act of the Assembly and received the rights with his Dutch-born brother William “as if they had been Englishmen born.” Were they considered “Dutch” before that? [4]

So what does this history have to do with my meandering story of the Thorowgoods in Virginia and their connections? First, one must grapple with the term “Dutch merchant.” Should that term be restricted to someone born of Dutch parents in the Netherlands who was engaged in trading goods in Dutch ships? Could it include those ex-patriots, born in England, but who migrated to the Netherlands to do business through Dutch or even English companies? What about those, like John Custis II, who were born in the Netherlands to English parents? Although John Custis II arrived in Virginia about 1651, he had to wait until 1658 before he was naturalized by an Act of the Assembly and received the rights with his Dutch-born brother William “as if they had been Englishmen born.” Were they considered “Dutch” before that? [4]

The nationality and birth place of those merchants sailing in and out of Dutch ports is not always known. The Dutch identity is further confused as “Dutch” is a language and adjective, not a country, but is usually associated with the country the Netherlands which was also known as the United Provinces, Dutch Republic, or Lowland Countries. However, that is not the same as Holland (an important province), and was distinct from Flanders or the Spanish Netherlands. Despite the confusions, much of the 17th century is viewed as the “Dutch Golden Age,” and the “Dutch” exerted great influence in the trade, arts, and politics of the time.

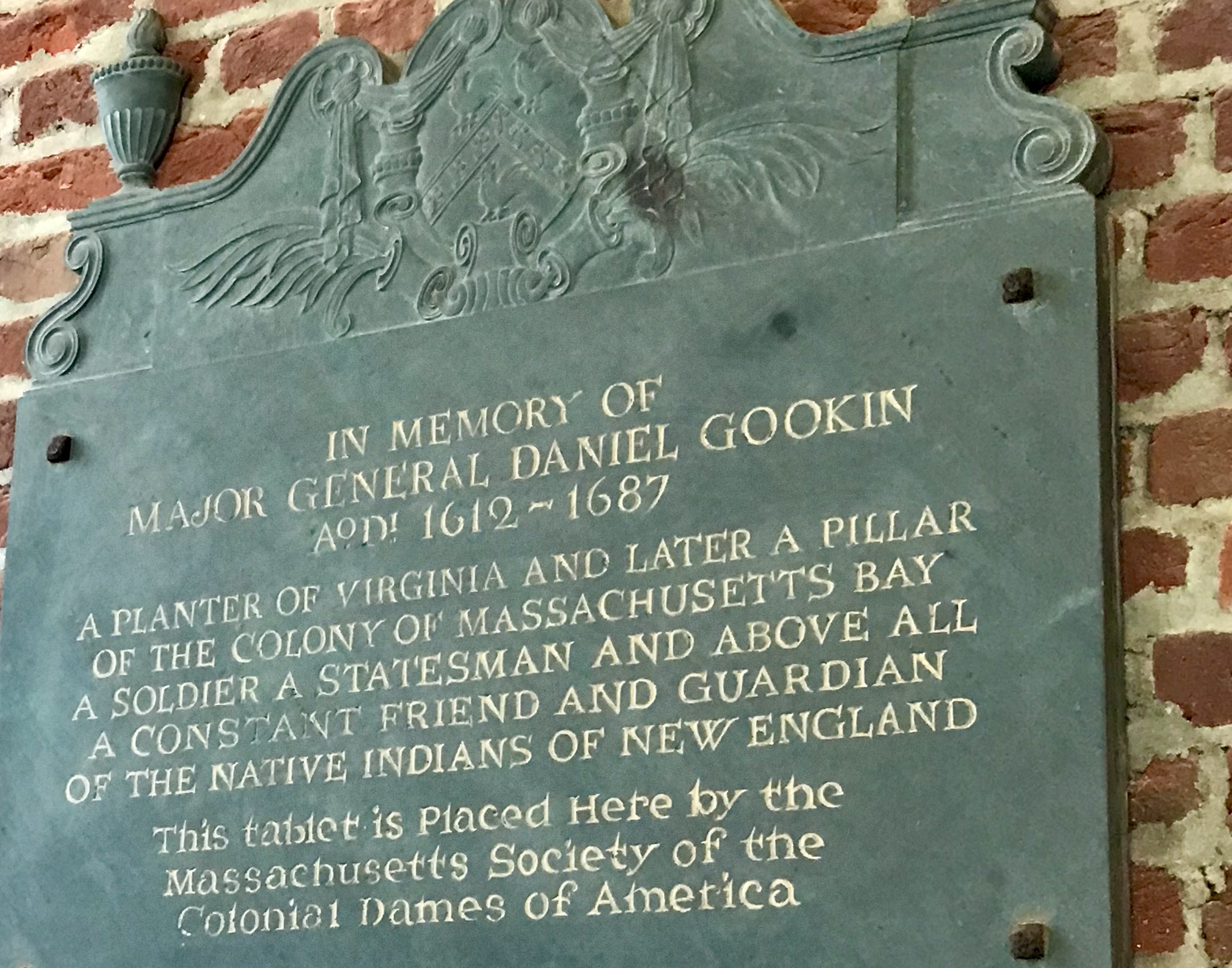

It was not surprising, then, that Capt. David DeVries, a noted Dutch explorer, visited Virginia in 1633. He had already had adventures in the Far East, encounters with indigenous tribes along the Delaware River, and provided service to the Dutch in New Netherlands. De Vries received a warm welcome from Virginia’s Gov. John Harvey, a former friend from their days in the East Indies. DeVries also visited Capt. Samuel Matthews, Capt. Stone, and Capt. Daniel Goegen (Gookin) along the Elizabeth River, through which he garnered valuable information about the the conditions, problems, and politics of the Virginia colony. DeVries visited Virginia thrice more in 1635, 1636, and 1643 . Daniel Gookin’s younger brother, John, with whom Daniel shared the plantation which DeVries visited, would become the second husband of Sarah Thorowgood Gookin Yeardley. [5]

During this time of Dutch presence in North America, strong mercantile ties were established between the English colonies, the Netherlands, and New Netherlands. Virginians found a ready market there for their quality tobacco and enjoyed the Dutch-style “free-trade” arrangements for importing goods. During the tumultuous years of the English Civil War in the 1640s, there was relative stability in dealing with the Dutch. Over 33 Dutch ships were known to be involved in Virginia’s tobacco trade then. [6]

During this time of Dutch presence in North America, strong mercantile ties were established between the English colonies, the Netherlands, and New Netherlands. Virginians found a ready market there for their quality tobacco and enjoyed the Dutch-style “free-trade” arrangements for importing goods. During the tumultuous years of the English Civil War in the 1640s, there was relative stability in dealing with the Dutch. Over 33 Dutch ships were known to be involved in Virginia’s tobacco trade then. [6]

Argoll Yearley and his brother Francis, who had married the then twice-widowed Sarah Thorowgood Gookin, were among those Virginia planters who sold to the Dutch. A Dutch connection was not surprising in that their father, Gov. George Yeardley, had been one of the early Virginia leaders who had fought in the Low Countries war for the independence of the Dutch Republic. It was in a journey with his shipment of tobacco to Rotterdam in 1649 that Argoll Yeardley married Ann Custis, the daughter of English ex-patriots Henry and Joan Custis who managed a popular inn there. Subsequently, not only Ann, but her uncle John Custis I and brothers John Custis II, William II, and Joseph came from the Netherlands to the Eastern Shore, though John I did not settle there. [7]

Argoll Yearley and his brother Francis, who had married the then twice-widowed Sarah Thorowgood Gookin, were among those Virginia planters who sold to the Dutch. A Dutch connection was not surprising in that their father, Gov. George Yeardley, had been one of the early Virginia leaders who had fought in the Low Countries war for the independence of the Dutch Republic. It was in a journey with his shipment of tobacco to Rotterdam in 1649 that Argoll Yeardley married Ann Custis, the daughter of English ex-patriots Henry and Joan Custis who managed a popular inn there. Subsequently, not only Ann, but her uncle John Custis I and brothers John Custis II, William II, and Joseph came from the Netherlands to the Eastern Shore, though John I did not settle there. [7]

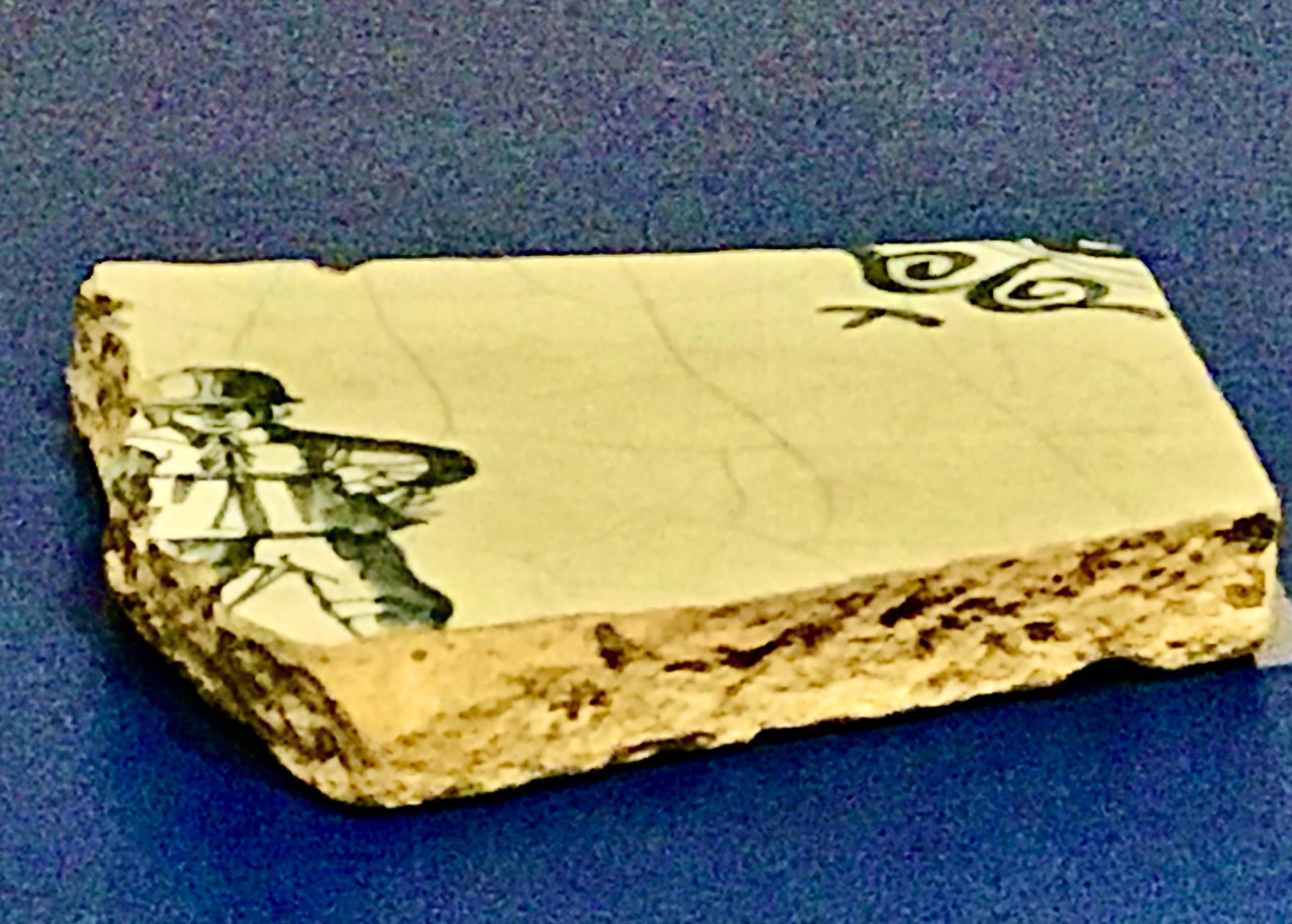

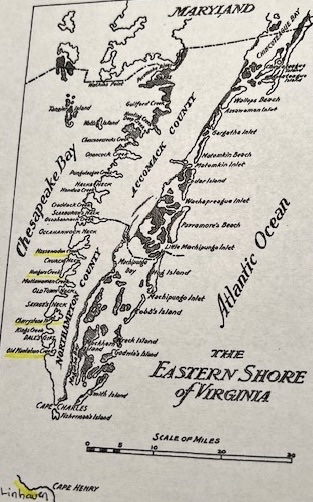

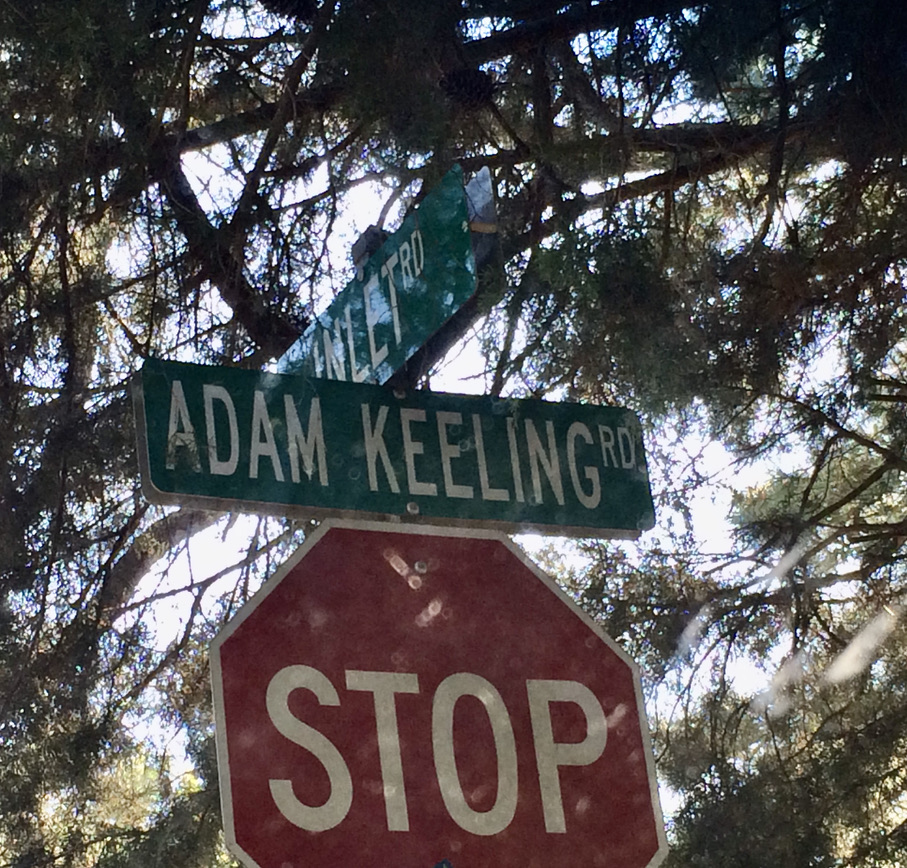

Exciting new archaeological evidence has been found of early Dutch influence and trading at Eyreville on the Cherrystone Inlet of the Eastern Shore. Having been the site of John Howe’s home in the 1630s and of the yellow-brick lined foundation of the 1657 house of William Kendall, a successful merchant and court commissioner, the artifacts reveal that this was one of the earliest sites on the Eastern Shore with substantial evidence of Dutch trade and/or possible short-term occupation. Numerous Dutch-made tobacco pipes, ceramics, and a great quantity of yellow bricks from the Netherlands have been found in the excavations. [8]

During this same time, another English merchant living in Rotterdam moved to Lower Norfolk County, Virginia, with his two sons William II and Arthur. William Moseley I and his wife Suzanne brought with them jewels from Rotterdam to use as an exchange to purchase needed livestock for their new home in Virginia.

As recorded in the Lower Norfolk Court records in November 1652, William Moseley paid the equivalent of 612 guilders for nine cattle from Francis Yeardley using an enameled gold and diamond buckle for a hat band, a gold ring set with a diamond, ruby, saphire and emerald, and a gold enameled pendant with diamonds. In a gracious letter, Suzanne Moseley wrote that “I had rather your wife should wear them than any gentlewomen I yet know in the country and … I wish Ms. Yeardley health and prosperity to wear them.” [9]

It is not surprising then that the remains of the original house built in Lower Norfolk County by Adam and Sarah Thorowgood and continually lived in by Sarah and her subsequent husbands should be replete with artifacts of Dutch goods. In a study of Dutch trade goods and ceramics in the 17th century English colonies, it was noted that “one of the largest aggregations of Dutch artifactual remains yet found archaeologically in Virginia was recovered from the so-called Chesapean site, believed to have been part of Adam Thoroughgood’s seventeenth century land holdings.” As that house burned and was abandoned in the 1650s, the artifacts are a time capsule of Dutch influence in that area. In addition, the inventory taken at Francis Yeardley’s death in 1656 included, among other items,”ten Dutch pictures.” [10]

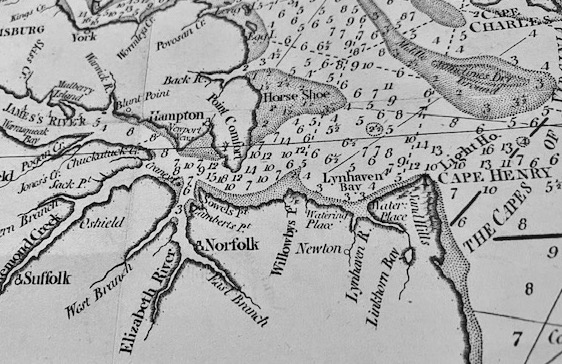

The complex interconnections are further evidenced in the experience of Augustine Herrman, a merchant born in Bohemia (now Czech Republic) who moved to Saxony (Germany), then the Netherlands, before coming to New Netherlands in 1644 as an agent for an Amsterdam merchant firm. As such, he traded with New Netherlands and New Sweden, then expanded into New England and the Chesapeake. He married Janetje Varleth of a notable Dutch merchant family and purchased land on the Eastern Shore of Virginia with the husband of his sister-in-law Ann Varleth, German-born Dr. George Hack. Hermann then expanded his networks south into Virginia’s Hampton Roads. He conducted business with the newly resident Dutch merchants John Michael and Simon Overzee, as well as John Custis, the Yeardleys, and Edmond Scarborough. Herrman also obtained land in St. Mary’s County, Maryland. As a skilled cartographer, successful merchant, and trusted negotiator, Herrman was asked to help resolve boundary disputes between the colonies. While Herrman may not have been able to satisfy all the claimants, he put his skills to creating one of best maps of the Chesapeake area of that time. [11]

However, not all were pleased with the profitable, free-flowing Dutch trade, especially in England, as the purpose of the colonies was to enrich the motherland. In an attempt to coerce and punish those colonies who remained loyal to the royalist cause, the Commonwealth Parliament in 1650 prohibited trade with the “notorious robbers and traitors ” in Antigua, Barbados, Bermuda, and Virginia and prohibited them from “any manner of commerce or traffic with any people whatsoever.” In addition, they declared that no foreign ships were allowed to trade with the English colonies without a permit from Parliament, a requirement that Parliament then turned into law in 1651 as the first of the Navigational Acts. Virginia’s Gov. Berkeley complained,

However, not all were pleased with the profitable, free-flowing Dutch trade, especially in England, as the purpose of the colonies was to enrich the motherland. In an attempt to coerce and punish those colonies who remained loyal to the royalist cause, the Commonwealth Parliament in 1650 prohibited trade with the “notorious robbers and traitors ” in Antigua, Barbados, Bermuda, and Virginia and prohibited them from “any manner of commerce or traffic with any people whatsoever.” In addition, they declared that no foreign ships were allowed to trade with the English colonies without a permit from Parliament, a requirement that Parliament then turned into law in 1651 as the first of the Navigational Acts. Virginia’s Gov. Berkeley complained,

“The Indians, God be blessed, round about us are subdued, we can only feare the Londoners, who would faine bring us to the same poverty, wherein the Dutch found and relieved us. [The Londoners] would take away the liberty of our consciences, and tongues, and our right of giving and selling our goods to whom we please.” [12]

Gov. Berkeley was dismissed; Virginia had to submit to the rule of Parliament; and the Anglo-Dutch trade suffered. Unlicensed Dutch vessels were captured in Virginia waters, and with the mounting tensions between the Netherlands and England, the first Anglo-Dutch War erupted on 30 June 1652. There were a series of naval battles as these two maritime powers fought for dominance over fishing grounds, trade in the East Indies and North America, and Caribbean possessions. It was a war that most English and Dutch colonists in America did not want, and it made Atlantic trade more risky. Northampton on the Eastern Shore even passed measures to protect Dutch traders. However, at the end of the war in 1654, enforcement of navigational restrictions was lax, especially in the outlying areas of the Eastern Shore and Lower Norfolk. The Dutch and Virginians became skilled at circumventing the laws. [13]

It was during this era that the daughters of Sarah and Adam Thorowgood were starting to come of age and be eligible for suitable marriages. In his will, Adam had given Sarah “guardianship of all of my children, until my daughters come to the age of sixteen years, and my son Adam to the age of one and twenty.” By 1649, Ann, the oldest, had married Job Chandler, an English immigrant who had lived not far from Francis Yeardley on the Eastern Shore and then apparently followed him to Lower Norfolk after Francis married Ann’s mother. Chandler purchased 240 acres there adjoining the Yeardleys. Although Chandler did not have Dutch ties himself, he quickly acquired connections. [14]

It was during this era that the daughters of Sarah and Adam Thorowgood were starting to come of age and be eligible for suitable marriages. In his will, Adam had given Sarah “guardianship of all of my children, until my daughters come to the age of sixteen years, and my son Adam to the age of one and twenty.” By 1649, Ann, the oldest, had married Job Chandler, an English immigrant who had lived not far from Francis Yeardley on the Eastern Shore and then apparently followed him to Lower Norfolk after Francis married Ann’s mother. Chandler purchased 240 acres there adjoining the Yeardleys. Although Chandler did not have Dutch ties himself, he quickly acquired connections. [14]

By 1646, the notable Dutch merchant, Simon (Symon) Overzee was trading for tobacco in Lower Norfolk County. In 1650, he and Francis Yeardley jointly purchased a Dutch ship, Het Wittepartt, for transporting tobacco. Job Chandler, who sometimes represented settlers in legal matters, did so for Simon Overzee in 1651. It was to this Simon Overzee that the second Thorowgood daughter, Sarah (II), was wed. Job and his wife Ann and Simon and his wife Sarah (II) soon thereafter moved to adjoining properties on Nangemy Creek in Charles County, Maryland. While in Maryland, Simon Overzee and Augustine Hermann set up a “firme Corpartnership and Common fellowship of trade and traffique for three yeares.” Even after the Overzees moved to the St. John’s house in St . Mary’s County, Maryland, he still continued to be actively involved in commerce in Lower Norfolk County and the Eastern Shore. It was at St. John’s that the tragic death of enslaved Antonio occurred. [15]

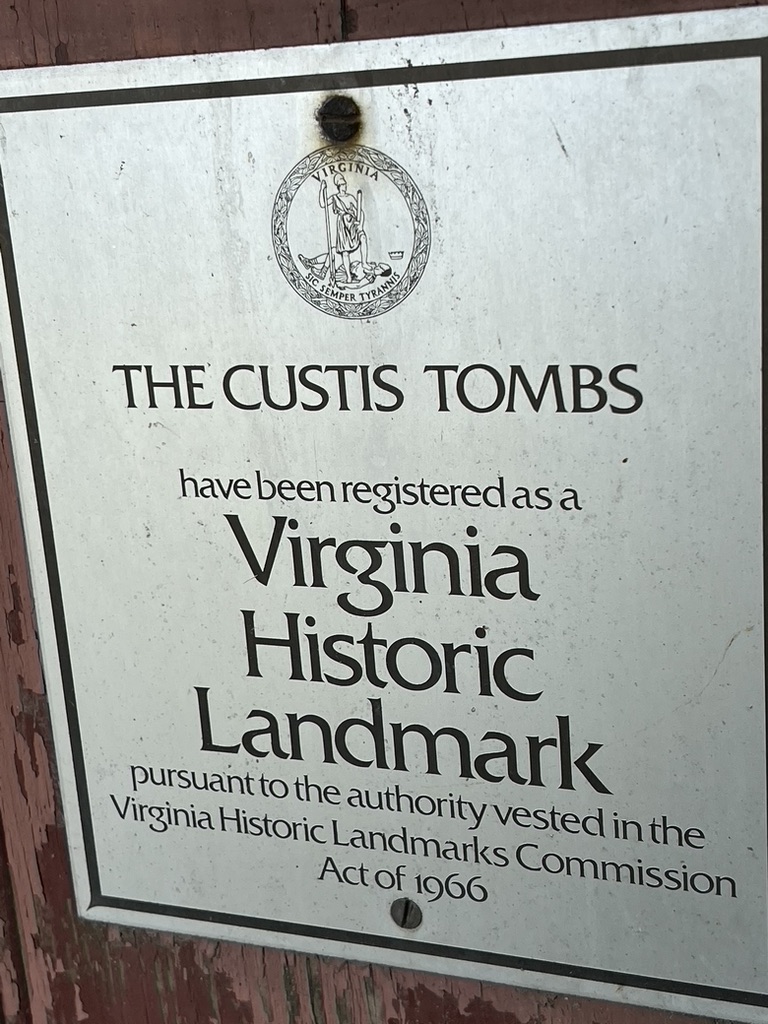

Elizabeth Thorowgood, Adam and Sarah’s third daughter, married John Michael (Machelle, Michielsz), a Dutch merchant from Graft, Holland, who was trading on the Eastern Shore by 1652. Michael was often asked to act as an attorney or representative in the affairs and disputes of other merchants from Amsterdam, New England, and Virginia. Still, in 1663, John Michael’s appointment to the Northampton Court was rescinded for a couple of months until he could provide proof that he was not an alien, but had been naturalized an English citizen. Margaret, a daughter of John and Elizabeth Thorowgood Michael, was the first wife of John Custis III and lived at Hunger’s Creek (Wilsonia) on the Eastern Shore. John Custis IV was one of her sons. [16]

Sarah Thorowgood Gookin Yeardley’s fourth daughter, Mary Gookin, was born from her second marriage. Mary would have only been about 15 years old when her mother died in 1657. However, the Dutch connection was maintained in her marriage as well. Mary married William Moseley II who had come with his parents from Rotterdam when they exchanged jewels for cattle with the Yeardleys in Lower Norfolk County. [17]

Notably, there was one Thorowgood groom, Adam Thorowgood II. He must have been quite young when his father Adam Thorowgood died in 1640, as he had not yet obtained his majority at the death of his mother in 1657. He, therefore, selected his brother-in-law Simon Overzee as his guardian. Nor did Adam II look much outside the family network when it was time to marry. He selected Frances Yeardley, the daughter of Argoll and his first wife. Although connected through marriages, they were not blood relations. Frances would have grown up under the influence of her step-mother, Ann Custis Yeardley. [18]

These marriages and families each have their own complex stories which have only been introduced in this post. Clearly, Dutch connections were part of their heritage. Their stories and that of the evolving colonial experience will be expanded in my subsequent posts.

In February 1657, Gov. Peter Stuyvesant and his New Netherlands Council called for a day of thanksgiving. The Anglo-Dutch war had ended, relations with the local tribes had improved, prosperity was increasing, settlement was expanding, and they had conquered New Sweden. Despite England’s attempts to regulate colonial trade, Dutch merchants were still doing a good, if illicit, business with the colonies. The Dutch had held their North American claim for nearly 50 years and anticipated that they were there to stay. [19]

In February 1657, Gov. Peter Stuyvesant and his New Netherlands Council called for a day of thanksgiving. The Anglo-Dutch war had ended, relations with the local tribes had improved, prosperity was increasing, settlement was expanding, and they had conquered New Sweden. Despite England’s attempts to regulate colonial trade, Dutch merchants were still doing a good, if illicit, business with the colonies. The Dutch had held their North American claim for nearly 50 years and anticipated that they were there to stay. [19]

However, in 1660 increased tensions between their motherlands led Gov. Stuyvesant and Gov. Berkeley, who had been reappointed with the Restoration, to create their own “Articles of amitie and commerce” to facilitate and protect trade between their colonies. However, Charles II increased trade restrictions and enforcement, and soon the Anglo-Dutch wars resumed. After an English fleet arrived at New Amsterdam, Peter Stuyvesant was forced to surrender on September 29, 1664. [20]

When the first Jamestown settlers built their fort, they installed cannon facing the James River, expecting to fight the Spanish. However, the Spanish never attacked. Despite years of friendship and mutually beneficial trade, it was the Dutch who ended up attacking Virginia. Dutch ships destroyed a fleet of Virginia tobacco ships at the mouth of the James River in 1667, and attacked ships in the Lynhaven Bay in Lower Norfolk County in 1673. In response, Virginia built the Half Moon Fort on the Elizabeth River (where Norfolk now stands) to protect themselves against further attacks. By then, England had aggressively captured New Netherlands, broken Dutch sea dominance, and established control over the North American eastern seaboard. Colonial resentment over England’s trade restrictions, however, continued to simmer until the Revolution a century later. [21]

When the first Jamestown settlers built their fort, they installed cannon facing the James River, expecting to fight the Spanish. However, the Spanish never attacked. Despite years of friendship and mutually beneficial trade, it was the Dutch who ended up attacking Virginia. Dutch ships destroyed a fleet of Virginia tobacco ships at the mouth of the James River in 1667, and attacked ships in the Lynhaven Bay in Lower Norfolk County in 1673. In response, Virginia built the Half Moon Fort on the Elizabeth River (where Norfolk now stands) to protect themselves against further attacks. By then, England had aggressively captured New Netherlands, broken Dutch sea dominance, and established control over the North American eastern seaboard. Colonial resentment over England’s trade restrictions, however, continued to simmer until the Revolution a century later. [21]

Special Thanks to Jenean Hall, Eastern Shore historian, for helping me locate and understand the Eastern Shore connections.

Footnotes:

[1] Jacobs, Jaap, The Colony of New Netherland: A Dutch Settlement in Seventeenth-Century America (Ithaca, New York: Cornell University, 2009), 21-22. “Henry Hudson,” accessed online on 4/3/2024 from Wikipedia at en.wikipedia.org/ wiki/Henry_ Hudson.

[2] Jacobs, 30-31. Romney, Susanah Shaw, New Netherland Connections: Intimate Networks and Atlantic Ties in Seventeenth-Century America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014), 13.

[3] Waldron, Richard, “New Sweden: An Interpretation,” in Revisiting New Netherland: Perspectives on Early Dutch America, ed. Joyce D. Goodfriend (Leiden: Brill, 2005), 73-75. Covart, Elizabeth, “New Sweden: A Brief History,” Penn State University Libraries (2004) accessed online on 3/15/2024 at Unearthing Past Student Research.

[4] Lynch, James B., Jr., The Custis Chronicles: The Years of Migration (Camden, Maine: Picton Press, 1992), 159-160.

[5] Parr, Charles McKew, The Voyages of David DeVries (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Co., 1969), 233; 236-238, 242-250. Lounsbury, Carl R., ” Golden Quarter” in The Material World of Eyre Hall: Four Centuries of Chesapeake History, ed. Carl R. Lounsbury (Baltimore: Maryland Center for History and Culture, 2021), 36. McCartney, Martha W. Jamestown People to 1800 (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company, 2012), 175-176. See John Gookin, Sarah Thorowgood, the Nansemond Tribe, and Virginia Puritans

[6] Truxes, Thomas M., The Overseas Trade of British America (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2021), 95-97. Lounsbury, 36-37. Jacobs, 142. Waldron, 104-105. Pagan, John R., “Dutch Maritime and Commercial Activity in Mid-Seventeenth-Century Virginia,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, 90:4 (October 1982), 488-491.

[7] Lynch, 137-169. Lounsbury, 37. McCartney, 131-133, 462-463. Leath, Robert A. “Dutch Trade and Its Influence on Seventeenth-Century Chesapeake Furniture, ” accessed online on 3/12/2024 through Chipstone Foundation https://chipstone.org/content.php/24/Copyright. (1993-2016). Hall, Jenean, Another Day: More Stories from the Early Colonial Records of Virginia’s Eastern Shore (Kwe Publishing, 2023), 100. See Unexpected: Ann Custis Yeardley & Sarah Yeardley Part II

[8] “Eyreville” National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (VLR Listed 6/15/2023; NRHP Listed 3/18/2024) Site VDHR #065-5126/44NH0507: Section 7: 27-30; Section 8: 39.

[9] “Virginia Council Journals” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, 35 (1927), 50-51. Brayton, John A., Transciption of Lower Norfolk County, Virginia Records Record Book “C” 16651-1656 Volume Two (Baltimore: Clearfield Company, 2010), 49-51 (24b). McCartney, 291.

[10] Wilcoxen, Charlotte, Dutch Trade and Ceramics in America in the Seventeenth Century (Albany: Albany Institute of History and Art, 1987), 21. Brayton, 435. See The Material Culture of Sarah Offley Thorowgood Gookin Yeardley

[11] Lounsbury, 38. Koot, Christian J., A Biography of a Map in Motion: Augustine Herrman’s Chesapeake (New York: New York University Press, 2018) 15-18, 25, 39-40. Whitelaw, Ralph T., Virginia’s Eastern Shore: A History of Northampton and Accomack Counties (Richmond, Virginia Historical Society, 1951), 687, 694-696]

[12] Pagan, 494.

[13] Truxes, 95. Pagan, 497. Jones, J.R., The Anglo-Dutch Wars of the Seventeenth Century (London: Longman Group, 1996), 11-12. Hainsworth, Roger and Christine Churches, The Anglo-Dutch Naval Wars 1652-1674 (Gloucestershire, England: Sutton Publishing, 1998), 16-18. Wise, Jennings Cropper, Ye Kingdome of Accawmacke of the Eastern Shore or Virginia in the Seventeenth Century (Richmond, The Bell Book and Stationary Co., 1911), 71. Leath (online).

[14]“The Thorowgood Family of Princess Anne County, Va, ” The Richmond Standard, 4: no. 13 (26 November 1882). Chandler, Joseph Barron, “Chandlers to Virginia 1607-1700, Part II” Tidewater Virginia Families: A Magazine of History and Genealogy, 12:3 (November/December 2003), 187-193. See Fascinating and Formidable Sarah Offley Gooking Yeardley

[15] Jones, Jacqueline, A Dreadful Deceit (New York: Basic Books, 2013), 13-17. Koot, 40. Parramore, Thomas C., Norfolk: The First Four Centuries (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1994), 37-39.

[16] Koot, 39. Mackey, Howard and Marlene A. Groves, Northhampton County Virginia Record Book Court Cases Vol.8 1637-1664 (Rockport, Maine: Picton Press, 2002), 330, 341, 339. Whitelaw, 107-117. Hall, Jenean, unpublished papers on John Michael, 2023.

[17] McCartney, 291.

[18] McCartney, 403, 463 . Brayton, John A., Transcription of Lower Norfolk County, Virginia Records Wills and Deeds, Book “D,” 1656-1666 Volume One (Memphis: Cain Lithographers, 2007), 108.

[19] Romney 9-12.

[20] Pagan, 497. Jones, J. R., 3-10.

[21] Jones, J.R., 217-224. Pagan, 500-501. Quarstein, John V.,”Hampton Roads Invaded: The Anglo-Dutch Naval Wars” published online by The Mariners’ Museum and Park, Yorktown, Virginia on Oct 15, 2020. Accessed online 9/13/2023 at http://www.marinersmuseum.org.

Eastern Shore and Lower Norfolk residents often shared merchant ties and attitudes from their common “outlier” status in the Virginia Colony. As the Thorowgood’s Lower Norfolk lands were close to Cape Henry at the entrance to the Chesapeake Bay, there would have been much shipping passing by, and it was a straight path from Hungars and Nassawadox Creek where the Yeardleys lived to the Thorowgood lands on the Lynnhaven Bay/River. So whether Francis came there for business or was looking for additional land and opportunities, he and several local acquaintances spent the night of June 10, 1647 at the house of the twice widowed Sarah Thorowgood Gookin.

Eastern Shore and Lower Norfolk residents often shared merchant ties and attitudes from their common “outlier” status in the Virginia Colony. As the Thorowgood’s Lower Norfolk lands were close to Cape Henry at the entrance to the Chesapeake Bay, there would have been much shipping passing by, and it was a straight path from Hungars and Nassawadox Creek where the Yeardleys lived to the Thorowgood lands on the Lynnhaven Bay/River. So whether Francis came there for business or was looking for additional land and opportunities, he and several local acquaintances spent the night of June 10, 1647 at the house of the twice widowed Sarah Thorowgood Gookin.

Ann’s acceptance of the marriage proposal brought the Custis family to Virginia. Her uncle, John Custis I, may have accompanied them or arrived shortly thereafter. Although John I conducted business, acquired property, and made periodic visits, he never settled there.

Ann’s acceptance of the marriage proposal brought the Custis family to Virginia. Her uncle, John Custis I, may have accompanied them or arrived shortly thereafter. Although John I conducted business, acquired property, and made periodic visits, he never settled there.

Shortly after the English Civil War began, Richard Ingle, the master of the ship Reformation and an avowed supporter of the parliamentary cause, got into an argument with Francis Yeardley about the King and Parliament while he was docked on the Eastern Shore. Argoll, who was also on board, attempted to calm them. However, Ingle grabbed a poleax and a cutlass and ordered all Virginians off his ship. As a Councillor and the Commander of the Eastern Shore, Argoll responded, “I arrest you in the King’s name.” Ingle replied, “If you had arrested me in the King and Parliaments name I would have obeyed it for so it is now.” He then forced the Virginians, including Francis and Argoll, to leave his ship and sailed to Maryland, boasting of his defiance of Yeardley. However, months later, Argoll forgave Inge “of and from all manner of debts, suits, and controversies.”[11]

Shortly after the English Civil War began, Richard Ingle, the master of the ship Reformation and an avowed supporter of the parliamentary cause, got into an argument with Francis Yeardley about the King and Parliament while he was docked on the Eastern Shore. Argoll, who was also on board, attempted to calm them. However, Ingle grabbed a poleax and a cutlass and ordered all Virginians off his ship. As a Councillor and the Commander of the Eastern Shore, Argoll responded, “I arrest you in the King’s name.” Ingle replied, “If you had arrested me in the King and Parliaments name I would have obeyed it for so it is now.” He then forced the Virginians, including Francis and Argoll, to leave his ship and sailed to Maryland, boasting of his defiance of Yeardley. However, months later, Argoll forgave Inge “of and from all manner of debts, suits, and controversies.”[11]

They likewise shared common grief in losing their Yeardley husbands a year apart: Argoll in 1655 and Francis in 1656. We do not know the circumstances of their deaths, but both died unexpectedly without wills. Did Sarah and Ann confide concerns about their husbands’ health or exchange condolences? Sarah died a year after Francis. They had not had any children together. [13]

They likewise shared common grief in losing their Yeardley husbands a year apart: Argoll in 1655 and Francis in 1656. We do not know the circumstances of their deaths, but both died unexpectedly without wills. Did Sarah and Ann confide concerns about their husbands’ health or exchange condolences? Sarah died a year after Francis. They had not had any children together. [13] Ann was appointed the executrix of Argoll’s estate when he died intestate. Settling his estate was complex. The inventory and appraisal of the estate on October 29, 1655 revealed that Argoll had 10 ewes, 16 cows, and 3 horses; 2 indentured servants with 3 months of service left in their contracts; and 2 Negro men, 2 Negro women (their wives), and 4 Negro children, only one of which was to be freed at adulthood (see prior post), providing further evidence that their Africans were enslaved, not indentured. The Yeardleys had lived comfortably with cupboards, beds, linens, a large Dutch looking glass (mirror), books, cookware, pewter, silver plate, a small boat, and more. Argoll’s estate was appraised at the equivalent of 41,269 pounds of tobacco which should have been adequate to pay off the usual debts.[14]

Ann was appointed the executrix of Argoll’s estate when he died intestate. Settling his estate was complex. The inventory and appraisal of the estate on October 29, 1655 revealed that Argoll had 10 ewes, 16 cows, and 3 horses; 2 indentured servants with 3 months of service left in their contracts; and 2 Negro men, 2 Negro women (their wives), and 4 Negro children, only one of which was to be freed at adulthood (see prior post), providing further evidence that their Africans were enslaved, not indentured. The Yeardleys had lived comfortably with cupboards, beds, linens, a large Dutch looking glass (mirror), books, cookware, pewter, silver plate, a small boat, and more. Argoll’s estate was appraised at the equivalent of 41,269 pounds of tobacco which should have been adequate to pay off the usual debts.[14] However, growers of tobacco and trade merchants lived in a world of credit, and their cash flow was often in flux. At the moment of Argoll’s unexpected death, he had extended his credit beyond his means, for Ann reported to the court in November 1655 that she had paid out “a considerable sum of tobacco beyond assets to the creditors of her dead husband.” Ann Yeardley was ordered to find what she could to pay debts, but was granted a Quietus Est or termination of remaining debts by the court. Fortunately, real estate was not included in the assessment, so Argoll II still inherited his father’s property, and Ann received her widow’s dower interest which she released to Argol II when he agreed to deed land to her sons (his stepbrothers). [ 15]

However, growers of tobacco and trade merchants lived in a world of credit, and their cash flow was often in flux. At the moment of Argoll’s unexpected death, he had extended his credit beyond his means, for Ann reported to the court in November 1655 that she had paid out “a considerable sum of tobacco beyond assets to the creditors of her dead husband.” Ann Yeardley was ordered to find what she could to pay debts, but was granted a Quietus Est or termination of remaining debts by the court. Fortunately, real estate was not included in the assessment, so Argoll II still inherited his father’s property, and Ann received her widow’s dower interest which she released to Argol II when he agreed to deed land to her sons (his stepbrothers). [ 15]

According to one conspirator’s confession, the plan also included hiring a ship of one of Edmund’s brothers (likely Robert who was a shipmaster) to smuggle additional arms into England. Edmund claimed that the arms he had in the house were to send to Virginia, but the Commonwealth Assembly had not requested them. Edmund was sent to prison with Norwood. After Captain Norwood had innocently stayed at the Yeardley’s home in 1650, he had gone to Jamestown and may have initiated the plot in conjunction with Governor Berkeley. Assets of 1,000 pounds from Governor Berkeley were subsequently funneled to Edmund Custis.[17]

According to one conspirator’s confession, the plan also included hiring a ship of one of Edmund’s brothers (likely Robert who was a shipmaster) to smuggle additional arms into England. Edmund claimed that the arms he had in the house were to send to Virginia, but the Commonwealth Assembly had not requested them. Edmund was sent to prison with Norwood. After Captain Norwood had innocently stayed at the Yeardley’s home in 1650, he had gone to Jamestown and may have initiated the plot in conjunction with Governor Berkeley. Assets of 1,000 pounds from Governor Berkeley were subsequently funneled to Edmund Custis.[17]

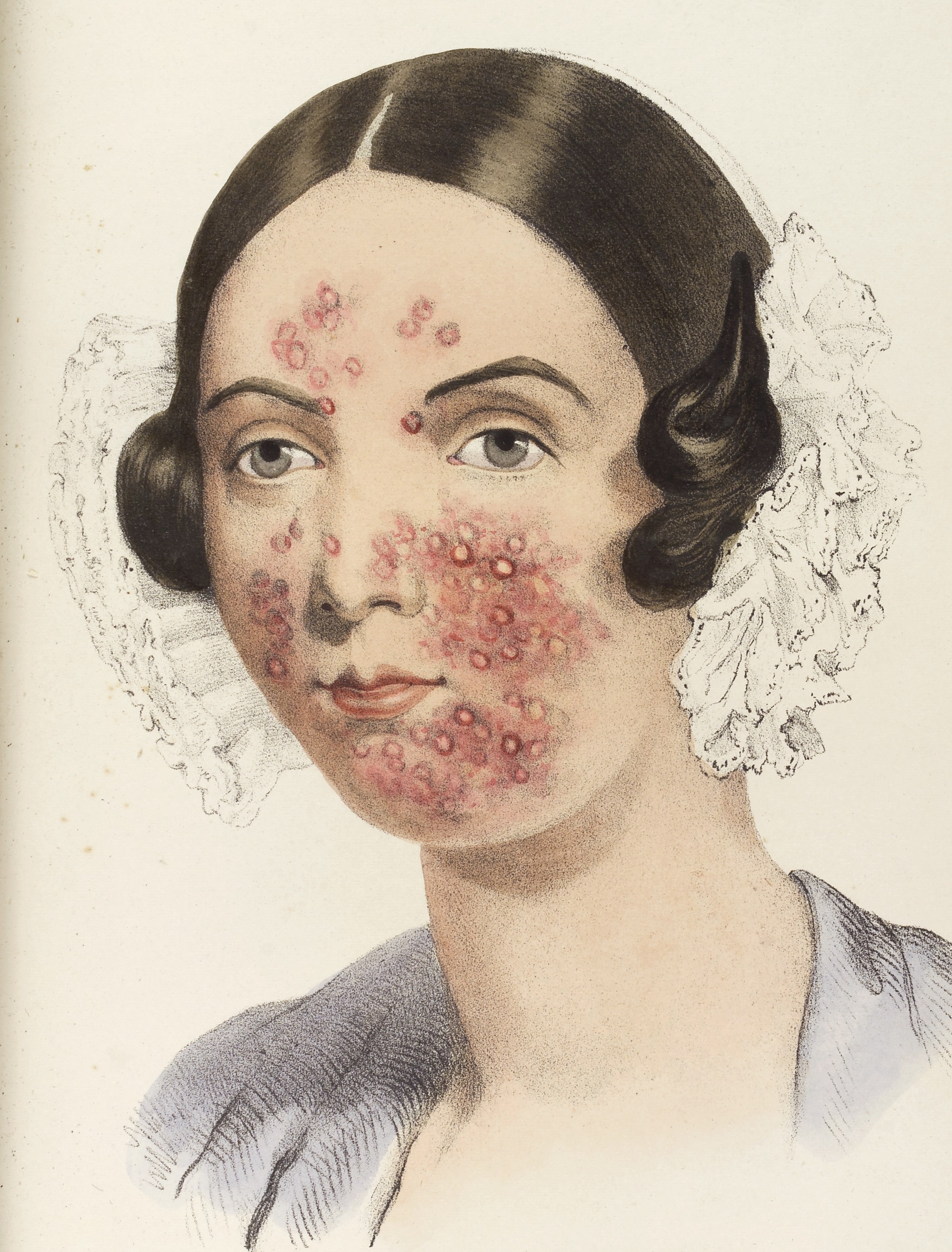

Sadly, it seems Ann was not cured at the time, but many questions remain unanswered. Was this a case of exorbitant doctor fees or lofty claims of a cure that could not be provided? A gesture of love or a demand for vanity? What sort of sores were these? It was likely more than a case of usual acne or hormonal imbalance, as Ann had borne children before. Perhaps, acne had worsened with streptococcus or staphylococcus bacteria. The sores did not sound like pox marks which would not have had seasonal variation.

Sadly, it seems Ann was not cured at the time, but many questions remain unanswered. Was this a case of exorbitant doctor fees or lofty claims of a cure that could not be provided? A gesture of love or a demand for vanity? What sort of sores were these? It was likely more than a case of usual acne or hormonal imbalance, as Ann had borne children before. Perhaps, acne had worsened with streptococcus or staphylococcus bacteria. The sores did not sound like pox marks which would not have had seasonal variation. In May 1662 just prior to his death, John Wilcocks prepared a will and shortly thereafter revised it. He left to his wife Ann his “whole estate real & personal lands and chattels during her natural life” which, on her decease, would go to their “child or children now in her womb.” But he was also inclusive of his stepsons, Henry and Edmond (Ann’s children with Argoll Yeardley), authorizing Ann to divide of his personal estate as inheritance for them as “to her shall seem fitting” and made them successively his heirs in case of the death of the child in the womb. He reminded his wife that he had “desired to be in some large measure helpful to the children or child of my brother Henry if he should have any.”

In May 1662 just prior to his death, John Wilcocks prepared a will and shortly thereafter revised it. He left to his wife Ann his “whole estate real & personal lands and chattels during her natural life” which, on her decease, would go to their “child or children now in her womb.” But he was also inclusive of his stepsons, Henry and Edmond (Ann’s children with Argoll Yeardley), authorizing Ann to divide of his personal estate as inheritance for them as “to her shall seem fitting” and made them successively his heirs in case of the death of the child in the womb. He reminded his wife that he had “desired to be in some large measure helpful to the children or child of my brother Henry if he should have any.” The Thorowgoods are rarely acknowledged in Eastern Shore history; yet as Francis’ wife, the powerful Sarah would have had some impact on affairs there. The Thorowgood genes and heritage infused the Eastern Shore through the marriage of her daughter Elizabeth Thorowgood to John Michaels, and thus to their Custis grandchildren. The Yeardley genes and heritage likewise came to Lower Norfolk through Argoll’s daughter Frances Yeardley II who married Adam Thorowgood II. The Thorowgood, Custis, and Yeardley women may not be the names that are usually remembered in history, but they played important roles in weaving the complex tapestry of the developing Virginia society.

The Thorowgoods are rarely acknowledged in Eastern Shore history; yet as Francis’ wife, the powerful Sarah would have had some impact on affairs there. The Thorowgood genes and heritage infused the Eastern Shore through the marriage of her daughter Elizabeth Thorowgood to John Michaels, and thus to their Custis grandchildren. The Yeardley genes and heritage likewise came to Lower Norfolk through Argoll’s daughter Frances Yeardley II who married Adam Thorowgood II. The Thorowgood, Custis, and Yeardley women may not be the names that are usually remembered in history, but they played important roles in weaving the complex tapestry of the developing Virginia society.

Sadly, very little was created and even less preserved to document the thoughts and lives of these women, so we must again turn to the stories and documents of the men to catch them in the shadows. In the prior post, the children of Gov. George and Lady Temperance Yeardley were left orphaned in Jamestown and returned to England under the guardianship of their uncle, Ralph Yeardley. Nothing is known of their English childhoods. Their uncle was an apothecary of the merchant class, but with the wealth and status of Sir & Lady Yeardley, these orphans likely had an advantageous upbringing and an acquaintance with the cultured ways of English society. The daughter Elizabeth then disappeared from the records, hopefully through marriage rather than death. Argoll and Francis reappeared when they returned to Virginia to claim their inheritances. (See

Sadly, very little was created and even less preserved to document the thoughts and lives of these women, so we must again turn to the stories and documents of the men to catch them in the shadows. In the prior post, the children of Gov. George and Lady Temperance Yeardley were left orphaned in Jamestown and returned to England under the guardianship of their uncle, Ralph Yeardley. Nothing is known of their English childhoods. Their uncle was an apothecary of the merchant class, but with the wealth and status of Sir & Lady Yeardley, these orphans likely had an advantageous upbringing and an acquaintance with the cultured ways of English society. The daughter Elizabeth then disappeared from the records, hopefully through marriage rather than death. Argoll and Francis reappeared when they returned to Virginia to claim their inheritances. (See  Sir George had left his sons the acreage he had received on the Eastern Shore (Chesapeake Penninsula) from the Accomac chieftain called The Laughing King. However, that was not where Argoll acquired his first property in Virginia. Before returning to Virginia, Argoll had married Frances Knight of London and so listed her as one of his headrights to patent 500 acres of land on Dumpling Island on the Nansemond River in Upper Norfolk County (later Nansemond Co.) in February 1637/38. An approximate birthdate of 1620 based on the 1624 Jamestown census would have made Argoll only about 18 years old when he patented land, which was unusually young for that time. There is some question as to the reference point of the ages on the Muster, and depositions given in 1630, indicate that Argoll and Francis were about two years older than reported on the Muster.* To maintain a land claim, it had to be “seated” (settled) and there had to be improvements made on the land. It is unknown what kind of improvements Argoll made there or whether he or Francis ever lived in Upper Norfolk . [2]

Sir George had left his sons the acreage he had received on the Eastern Shore (Chesapeake Penninsula) from the Accomac chieftain called The Laughing King. However, that was not where Argoll acquired his first property in Virginia. Before returning to Virginia, Argoll had married Frances Knight of London and so listed her as one of his headrights to patent 500 acres of land on Dumpling Island on the Nansemond River in Upper Norfolk County (later Nansemond Co.) in February 1637/38. An approximate birthdate of 1620 based on the 1624 Jamestown census would have made Argoll only about 18 years old when he patented land, which was unusually young for that time. There is some question as to the reference point of the ages on the Muster, and depositions given in 1630, indicate that Argoll and Francis were about two years older than reported on the Muster.* To maintain a land claim, it had to be “seated” (settled) and there had to be improvements made on the land. It is unknown what kind of improvements Argoll made there or whether he or Francis ever lived in Upper Norfolk . [2] A few months later in September 1638, Argoll Yeardley, was designated as Esquire (a gentleman, not a lawyer) and was granted 3700 acres as his father’s inheritance on Hungars Creek in Accomack Co. (later Northampton Co.) of the Eastern Shore. Despite his young age, he was quickly accepted into the developing elite Virginia society and was recommended by Sir Francis Wyatt for his Governor’s Council. While Burgesses were elected, councillors were recommended by the governor and appointed for life by the King, with vacancies often filled by the sons or relatives of former councillors. Argoll would have served briefly with Adam Thorowgood on the Council before Adam suddenly died in 1640. [3]

A few months later in September 1638, Argoll Yeardley, was designated as Esquire (a gentleman, not a lawyer) and was granted 3700 acres as his father’s inheritance on Hungars Creek in Accomack Co. (later Northampton Co.) of the Eastern Shore. Despite his young age, he was quickly accepted into the developing elite Virginia society and was recommended by Sir Francis Wyatt for his Governor’s Council. While Burgesses were elected, councillors were recommended by the governor and appointed for life by the King, with vacancies often filled by the sons or relatives of former councillors. Argoll would have served briefly with Adam Thorowgood on the Council before Adam suddenly died in 1640. [3] In January 1641/42, Argoll was also appointed a commissioner and justice for Accomack County. However, not all residents were content with this young man’s authority. A contentious resident Thomas Parks was sent for trial by the Council (of which Argoll was a part) in 1643 for insulting and slandering Argoll’s parents’ background, disputing Argoll’s fairness, and threatening to take his grievances to Maryland or the native tribes (which could have stirred up trouble). Parke did not seem to learn that disrespect toward those in authority would not be tolerated, as he reappeared in court a few months later for affronting Yeardley and other commissioners and received 30 lashes. Two years later, he defamed Commissioner Obedience Robins, but was spared another whipping when he finally apologized. However, the councillors themselves were not above reprimands. Argoll himself was charged with contempt in 1644. [4]

In January 1641/42, Argoll was also appointed a commissioner and justice for Accomack County. However, not all residents were content with this young man’s authority. A contentious resident Thomas Parks was sent for trial by the Council (of which Argoll was a part) in 1643 for insulting and slandering Argoll’s parents’ background, disputing Argoll’s fairness, and threatening to take his grievances to Maryland or the native tribes (which could have stirred up trouble). Parke did not seem to learn that disrespect toward those in authority would not be tolerated, as he reappeared in court a few months later for affronting Yeardley and other commissioners and received 30 lashes. Two years later, he defamed Commissioner Obedience Robins, but was spared another whipping when he finally apologized. However, the councillors themselves were not above reprimands. Argoll himself was charged with contempt in 1644. [4]

The Eastern Shore settlement grew outwards along the bayside from the inlet at Old Plantation and the Ackomack River (later called Cherrystone) to King’s Creek and further up to Hungars and Nassawadox where the Yeardleys lived. As the land was divided by many streams and inlets, travel would have been challenging, going either by skiff (small open boat) or by walking paths around the water and marshy lands. It is likely that most of Frances’ social network would have been within a five mile radius (journey of an hour or two), as was found in a study of 17th c women in the Chesapeake area. Church and court days would have increased opportunities to develop relationships. [5]

The Eastern Shore settlement grew outwards along the bayside from the inlet at Old Plantation and the Ackomack River (later called Cherrystone) to King’s Creek and further up to Hungars and Nassawadox where the Yeardleys lived. As the land was divided by many streams and inlets, travel would have been challenging, going either by skiff (small open boat) or by walking paths around the water and marshy lands. It is likely that most of Frances’ social network would have been within a five mile radius (journey of an hour or two), as was found in a study of 17th c women in the Chesapeake area. Church and court days would have increased opportunities to develop relationships. [5] Frances must have been delighted when Argoll got a horse in 1642 (the first known horse purchased on the Eastern Shore) and continued to expand his herd. Hopefully, Frances had use of the horses, although it might have created some local jealousy as happened when Sarah Thorowgood rode her horse in Lower Norfolk. Overall, horses continued to be scarce on the Eastern Shore with only 6 landowners having horses by 1650 which only grew to 22 by 1655.

Frances must have been delighted when Argoll got a horse in 1642 (the first known horse purchased on the Eastern Shore) and continued to expand his herd. Hopefully, Frances had use of the horses, although it might have created some local jealousy as happened when Sarah Thorowgood rode her horse in Lower Norfolk. Overall, horses continued to be scarce on the Eastern Shore with only 6 landowners having horses by 1650 which only grew to 22 by 1655.

Despite Francis’ young age and lack of any military experience, Gov. Berkeley appointed him as a captain of the militia shortly after his arrival in Virginia. Francis had the authority “to appoint subordinate officers, exercise his company once a month, and levy a special tax to raise funds for the purchase of a drum, colors, and tent” for the King’s Creek to Hungars Creek area. Although relations were generally peaceful with the Accomac tribe on the Eastern Shore when Francis was appointed, the militia was reorganized shortly thereafter in response to increasing colony concerns in the era of the third Anglo-Powhatan War from 1644-1646. Francis continued as a captain, but Argoll eventually became the Commander of the Eastern Shore. [12]

Despite Francis’ young age and lack of any military experience, Gov. Berkeley appointed him as a captain of the militia shortly after his arrival in Virginia. Francis had the authority “to appoint subordinate officers, exercise his company once a month, and levy a special tax to raise funds for the purchase of a drum, colors, and tent” for the King’s Creek to Hungars Creek area. Although relations were generally peaceful with the Accomac tribe on the Eastern Shore when Francis was appointed, the militia was reorganized shortly thereafter in response to increasing colony concerns in the era of the third Anglo-Powhatan War from 1644-1646. Francis continued as a captain, but Argoll eventually became the Commander of the Eastern Shore. [12] Francis did not appear to have his older brother’s business skills. In a tobacco economy based upon the annual sale of the crop, it could be tricky to manage finances. While Francis was land rich, his bills were not always paid on time. In 1646, the county court on which his brother sat found Francis owed Thomas Savage, a cooper/carpenter, for his 4 years of service (possibly from an indentureship) 2 suits of clothes, 2 pair shoes, Irish stockings, 2 shirts, 1 cap, and 1 servants bed. Mr. Stephen Charlton had earlier warned a prospective worker to avoid working for Mr. Yeardley who, though a gentleman, had not given Thomas Savage anything for his work for 2 years. Francis Yeardley was also ordered in 1646 to pay his debts of £6+ to Obedience Robins and 50 guilders to William Waters. The bachelor Francis, though, was resourceful and improved his situation that next year by moving and marrying a rich Virginia widow. [13]

Francis did not appear to have his older brother’s business skills. In a tobacco economy based upon the annual sale of the crop, it could be tricky to manage finances. While Francis was land rich, his bills were not always paid on time. In 1646, the county court on which his brother sat found Francis owed Thomas Savage, a cooper/carpenter, for his 4 years of service (possibly from an indentureship) 2 suits of clothes, 2 pair shoes, Irish stockings, 2 shirts, 1 cap, and 1 servants bed. Mr. Stephen Charlton had earlier warned a prospective worker to avoid working for Mr. Yeardley who, though a gentleman, had not given Thomas Savage anything for his work for 2 years. Francis Yeardley was also ordered in 1646 to pay his debts of £6+ to Obedience Robins and 50 guilders to William Waters. The bachelor Francis, though, was resourceful and improved his situation that next year by moving and marrying a rich Virginia widow. [13] So, how did Ann Custis from Rotterdam and Sarah Offley Thorowgood Gookin from Lower Norfolk County, Virginia, get entangled in this story and end up as sisters in law? What impact did they have on the Eastern Shore story? Did Sarah really run a tavern? And whose complexion was worth 1,000 lbs. of tobacco?

So, how did Ann Custis from Rotterdam and Sarah Offley Thorowgood Gookin from Lower Norfolk County, Virginia, get entangled in this story and end up as sisters in law? What impact did they have on the Eastern Shore story? Did Sarah really run a tavern? And whose complexion was worth 1,000 lbs. of tobacco?

Inspired by Cromwell’s successes, Parliament was preparing at the end of 1644 to reorganize its army into the national New Model Army which would emphasize efficiency and merit. In an attempt to make this new army less political, those serving in both the military and Parliament were forced to choose between those positions through the Self-Denying Ordinance. However, the army ended up with greater representation of Independents like Cromwell than fervent Presbyterians which ultimately resulted in its own conflicts. While the New Model Army’s focus was to win battles, there was a general religious orientation, and they were issued a special Soldiers Catechism. It was also the first time there was a national uniform created for the troops who became called “redcoats.” [5]

Inspired by Cromwell’s successes, Parliament was preparing at the end of 1644 to reorganize its army into the national New Model Army which would emphasize efficiency and merit. In an attempt to make this new army less political, those serving in both the military and Parliament were forced to choose between those positions through the Self-Denying Ordinance. However, the army ended up with greater representation of Independents like Cromwell than fervent Presbyterians which ultimately resulted in its own conflicts. While the New Model Army’s focus was to win battles, there was a general religious orientation, and they were issued a special Soldiers Catechism. It was also the first time there was a national uniform created for the troops who became called “redcoats.” [5]

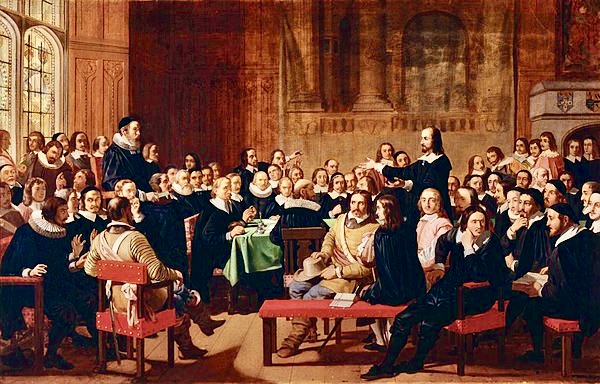

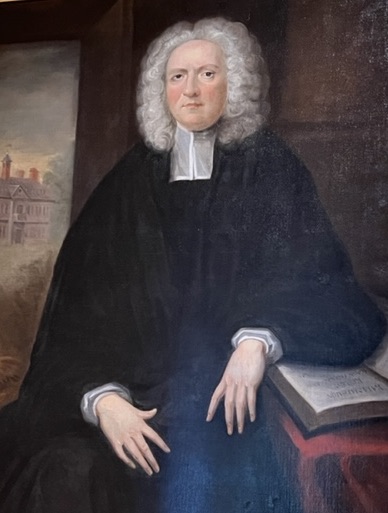

In April 1642, Parliament authorized the calling of an Anglo-Scottish synod of “divines” to revise the prayer book (rejecting the Anglican Common Book of Prayer) and decide matters regarding acceptable church liturgy, practices, and governance. Invited were 121 ordained ministers, 10 peers, 20 MPs as lay assessors, and 8 Scots (5 clerics and 3 laymen). The Assembly opened on July 1, 1643 at Westminster and continued until 1653. No Anglican ministers were appointed. Thomas Thorowgood was one of two selected to represent Norfolk, and he served from 1643 until 1649. In 1646, the Assembly published a New Confession of Faith based on Calvinistic doctrine and prescribed a Presbyterian form of church governance. Although the church in Scotland continued to employ the Westminster Assembly’s standards, they were revoked in England in 1660 when the Anglican Church was reinstated with the restoration of Charles II. [8]

In April 1642, Parliament authorized the calling of an Anglo-Scottish synod of “divines” to revise the prayer book (rejecting the Anglican Common Book of Prayer) and decide matters regarding acceptable church liturgy, practices, and governance. Invited were 121 ordained ministers, 10 peers, 20 MPs as lay assessors, and 8 Scots (5 clerics and 3 laymen). The Assembly opened on July 1, 1643 at Westminster and continued until 1653. No Anglican ministers were appointed. Thomas Thorowgood was one of two selected to represent Norfolk, and he served from 1643 until 1649. In 1646, the Assembly published a New Confession of Faith based on Calvinistic doctrine and prescribed a Presbyterian form of church governance. Although the church in Scotland continued to employ the Westminster Assembly’s standards, they were revoked in England in 1660 when the Anglican Church was reinstated with the restoration of Charles II. [8]

This approach to Christmas was not well received by the populace. Apprentices who lost their day off rioted in London against shop owners who complied with keeping their shops open in non-observance of the holiday. Some homes and even a few Puritan churches continued to decorate for Christmas. The declared Puritan days of fasts and thanksgivings never captured the hearts and imaginations of the people or produced a communal feeling like the religious festivals had. The denial of such entertainments only led to increased noncompliance and resentment against Puritan leaders. [13]

This approach to Christmas was not well received by the populace. Apprentices who lost their day off rioted in London against shop owners who complied with keeping their shops open in non-observance of the holiday. Some homes and even a few Puritan churches continued to decorate for Christmas. The declared Puritan days of fasts and thanksgivings never captured the hearts and imaginations of the people or produced a communal feeling like the religious festivals had. The denial of such entertainments only led to increased noncompliance and resentment against Puritan leaders. [13]  Noting that the choice of the date and manner of the Christmas celebration had more to do with the pagan solstice celebrations than Christ’s actual birth date which Rev. Thorowgood and others had concluded was likely in the spring, Thorowgood expressed willingness to accept another date and manner of celebrating the birth:

Noting that the choice of the date and manner of the Christmas celebration had more to do with the pagan solstice celebrations than Christ’s actual birth date which Rev. Thorowgood and others had concluded was likely in the spring, Thorowgood expressed willingness to accept another date and manner of celebrating the birth:

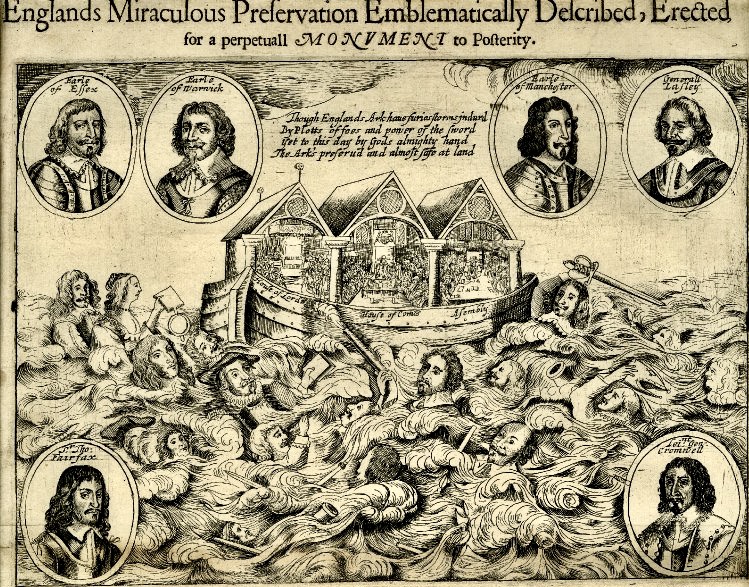

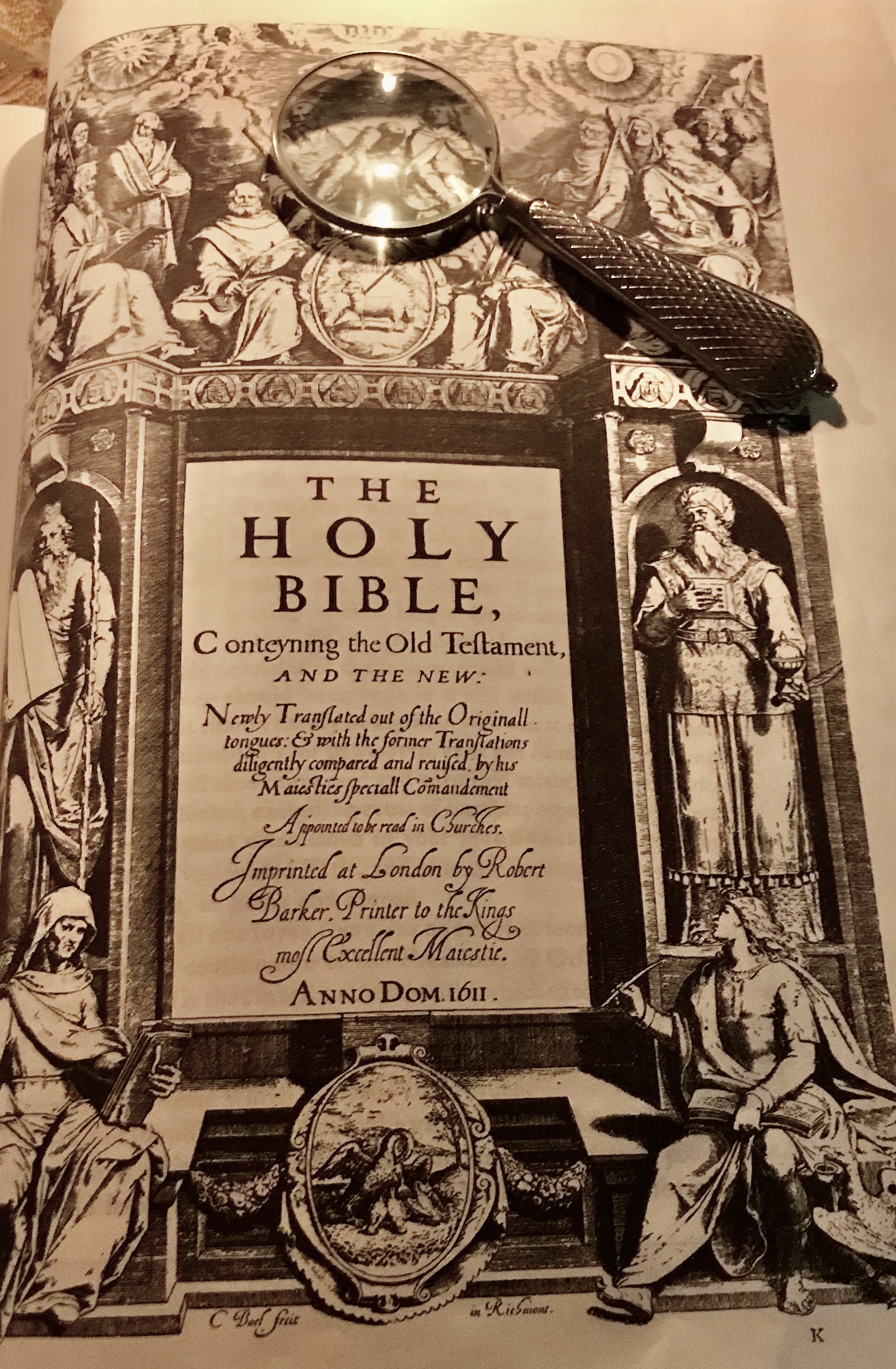

In 1589, John Aylmer, who became Bishop of London, declared that “God is English.” That same year Richard Hakluyt glorified the efforts of English colonization in North America to spread the “true” religion. In 1610, William Crashaw preached that England and the struggling Virginia colonists were “the friend of God.” The Protestant English of the 17th century believed they were now God’s chosen people and that, like the Israelites of the Old Testament, God intended them to possess this new promised land. [3]

In 1589, John Aylmer, who became Bishop of London, declared that “God is English.” That same year Richard Hakluyt glorified the efforts of English colonization in North America to spread the “true” religion. In 1610, William Crashaw preached that England and the struggling Virginia colonists were “the friend of God.” The Protestant English of the 17th century believed they were now God’s chosen people and that, like the Israelites of the Old Testament, God intended them to possess this new promised land. [3]

As noted in the last post, Daniel Gookin, Richard Bennett, and 69 others from the Nansemond area requested ministers from Puritans in New England in May 1642. Their letter was received favorably by the elders of Christ Church in Boston and, after consideration, three suitable ministers were sent to Virginia: William Tompson, John Knowles, and Thomas James. Wanting to be respectful of the Virginian leaders, they arrived with a letter of introduction from Gov. Winthrop to Virginia’s relatively new Gov. William Berkeley. Although the Assembly initially seemed pleased that colonists had successfully solicited ministers, Berkeley did not welcome them. However, many Virginians responded to their religious fervor. It was reported they “preached openly unto the people for some space of time, and also from house to house exhorted the people daily that they would cleave unto the Lord; the harvest they had was plentiful for the little space of time they were there.” Knowles reported, “The people’s hearts were inflamed with desire to hear them.” [18]

As noted in the last post, Daniel Gookin, Richard Bennett, and 69 others from the Nansemond area requested ministers from Puritans in New England in May 1642. Their letter was received favorably by the elders of Christ Church in Boston and, after consideration, three suitable ministers were sent to Virginia: William Tompson, John Knowles, and Thomas James. Wanting to be respectful of the Virginian leaders, they arrived with a letter of introduction from Gov. Winthrop to Virginia’s relatively new Gov. William Berkeley. Although the Assembly initially seemed pleased that colonists had successfully solicited ministers, Berkeley did not welcome them. However, many Virginians responded to their religious fervor. It was reported they “preached openly unto the people for some space of time, and also from house to house exhorted the people daily that they would cleave unto the Lord; the harvest they had was plentiful for the little space of time they were there.” Knowles reported, “The people’s hearts were inflamed with desire to hear them.” [18]  The conflict became particularly heated in the Elizabeth River Parish of Lower Norfolk County when the popular Puritan Rev. Harrison was charged with nonconformity in 1645 by the Anglican justices of a divided county court. When Harrison left and went to the welcoming Nansemond parishes, William Durand, an unordained minister, began to preach Puritan doctrine in his stead, but was arrested, and his unauthorized flock was told to disperse. Puritan Cornelius Lloyd, a Lower Norfolk Burgess, and his brother Edward Lloyd, a former Burgess, came to Durand’s defense which resulted in them being accused as “abettors to much sedition and mutiny.” In 1648, Berkeley and his council banished Harrison and Durand from the colony. That next year when Charles I was deposed, Virginia Puritans appealed to the English Parliamentary Council of State who ordered Berkeley to reinstate the Rev. Harrison, but he had already left for New England and never returned. [20]

The conflict became particularly heated in the Elizabeth River Parish of Lower Norfolk County when the popular Puritan Rev. Harrison was charged with nonconformity in 1645 by the Anglican justices of a divided county court. When Harrison left and went to the welcoming Nansemond parishes, William Durand, an unordained minister, began to preach Puritan doctrine in his stead, but was arrested, and his unauthorized flock was told to disperse. Puritan Cornelius Lloyd, a Lower Norfolk Burgess, and his brother Edward Lloyd, a former Burgess, came to Durand’s defense which resulted in them being accused as “abettors to much sedition and mutiny.” In 1648, Berkeley and his council banished Harrison and Durand from the colony. That next year when Charles I was deposed, Virginia Puritans appealed to the English Parliamentary Council of State who ordered Berkeley to reinstate the Rev. Harrison, but he had already left for New England and never returned. [20]

Another important trader on the Chesapeake was the Dutch merchant Simon Overzee who married Adam and Sarah Thorowgood’s daughter Sarah and moved from Virginia to St. Mary’s County in the 1650s. The Thorowgood’s daughter Ann married Job Chandler, a friend of the Maryland governor, and also moved to Maryland in 1651. With the increasing persecution in Virginia, ultimately about 300 Puritan men, women, and children decided to leave their homes in Virginia in the 1650s. These Virginians established the town Providence, now known as Annapolis, in Maryland where they received fertile land as well as “the liberty of our consciences in matter of religion and all other privileges of English subjects.” Ironically, the Act of Toleration that had initially protected those Puritans was repealed when they took over the Maryland government in 1652, but it was reinstated in 1657. [22]

Another important trader on the Chesapeake was the Dutch merchant Simon Overzee who married Adam and Sarah Thorowgood’s daughter Sarah and moved from Virginia to St. Mary’s County in the 1650s. The Thorowgood’s daughter Ann married Job Chandler, a friend of the Maryland governor, and also moved to Maryland in 1651. With the increasing persecution in Virginia, ultimately about 300 Puritan men, women, and children decided to leave their homes in Virginia in the 1650s. These Virginians established the town Providence, now known as Annapolis, in Maryland where they received fertile land as well as “the liberty of our consciences in matter of religion and all other privileges of English subjects.” Ironically, the Act of Toleration that had initially protected those Puritans was repealed when they took over the Maryland government in 1652, but it was reinstated in 1657. [22]

Cromwell’s Commonwealth ended shortly after his death, and by the time King Charles II ascended to the throne, Berkeley had been returned as Virginia’s governor. Berkeley was less strident in his persecution of religious dissidents in his second term, but faced other challenges building to Bacon’s Rebellion in 1675.

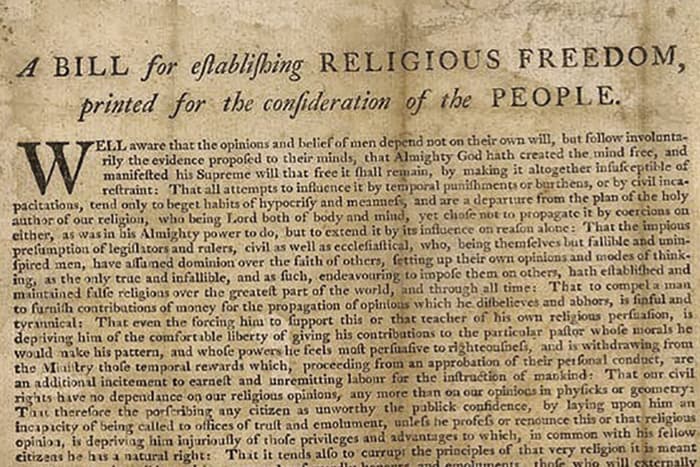

Cromwell’s Commonwealth ended shortly after his death, and by the time King Charles II ascended to the throne, Berkeley had been returned as Virginia’s governor. Berkeley was less strident in his persecution of religious dissidents in his second term, but faced other challenges building to Bacon’s Rebellion in 1675.  Under Bishop Compton’s commissaries, Virginia became more solidly Anglican in the 18th century. Persecution continued against nonconformists who expanded to include Presbyterians, Baptists, and Methodists. It was not until the throes of the American Revolution that Thomas Jefferson’s bill The Virginia Statute for Establishing Religious Freedom, was proposed, although it was not passed by the Virginia Assembly until 1786. At last there was separation of church and state, and Virginians were free to select their own faith without coercion or persecution. [26]

Under Bishop Compton’s commissaries, Virginia became more solidly Anglican in the 18th century. Persecution continued against nonconformists who expanded to include Presbyterians, Baptists, and Methodists. It was not until the throes of the American Revolution that Thomas Jefferson’s bill The Virginia Statute for Establishing Religious Freedom, was proposed, although it was not passed by the Virginia Assembly until 1786. At last there was separation of church and state, and Virginians were free to select their own faith without coercion or persecution. [26]

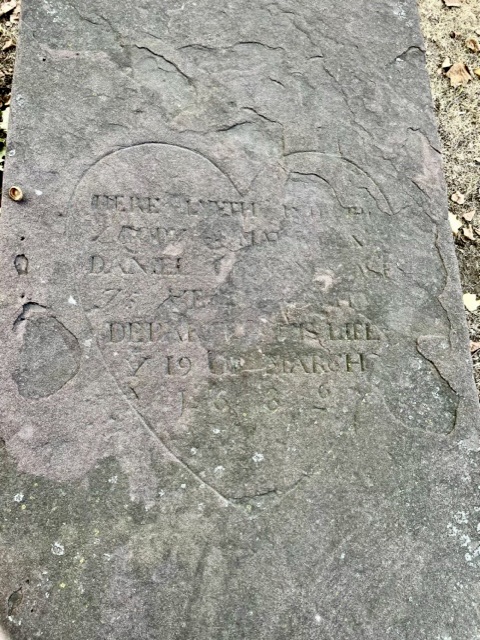

Likely inspired by them, Daniel Gookin Sr. had an approved proposal to bring cattle out of Ireland to Virginia by November 1620, and in July 1621, he asked the Council to be granted a plantation as large as was given to William Neuce. Daniel Gookin Sr. arrived in Virginia from Ireland in November 1621 on the Flying Harte to the acclaim of the Virginia Council:[5]

Likely inspired by them, Daniel Gookin Sr. had an approved proposal to bring cattle out of Ireland to Virginia by November 1620, and in July 1621, he asked the Council to be granted a plantation as large as was given to William Neuce. Daniel Gookin Sr. arrived in Virginia from Ireland in November 1621 on the Flying Harte to the acclaim of the Virginia Council:[5]

Good real estate often stays good real estate. The site that Daniel Gookin Sr. chose on the James River not far from the confluence with the Nansemond River is today covered by the Newport News shipyard (America’s largest industrial shipbuilder) and a terminus for the largest coal exporting site in the U.S. While nothing of Marie’s Mount remains to be found, a small window opened between 1928 and 1935 when a Newport News physician, Jerome Knowles, found a large exposed 17th century trash pit on the eroding banks of the James River in the area of Marie’s Mount. Dr. Knowles eventually donated the artifacts to Iver Noel Hume, the director of archaeology for Colonial Williamsburg, where the collection still resides. Dr. Hume noted the artifacts were from the 2nd quarter of the 17th century (the Gookin era) and stated there was “the finest group of Pisa marbled slipwares that I have seen or heard of from any other site.” The quantity and type of artifacts in this happenstance collection seemed to be in line with the presence of around 30-50 people at the Gookin site. [8]

Good real estate often stays good real estate. The site that Daniel Gookin Sr. chose on the James River not far from the confluence with the Nansemond River is today covered by the Newport News shipyard (America’s largest industrial shipbuilder) and a terminus for the largest coal exporting site in the U.S. While nothing of Marie’s Mount remains to be found, a small window opened between 1928 and 1935 when a Newport News physician, Jerome Knowles, found a large exposed 17th century trash pit on the eroding banks of the James River in the area of Marie’s Mount. Dr. Knowles eventually donated the artifacts to Iver Noel Hume, the director of archaeology for Colonial Williamsburg, where the collection still resides. Dr. Hume noted the artifacts were from the 2nd quarter of the 17th century (the Gookin era) and stated there was “the finest group of Pisa marbled slipwares that I have seen or heard of from any other site.” The quantity and type of artifacts in this happenstance collection seemed to be in line with the presence of around 30-50 people at the Gookin site. [8]

John ultimately acquired 1490 acres, including 640 acres in Lower Norfolk County adjoining the Thorowgood estate in October 1641 after his marriage to Sarah Thorowgood. This land came to him for transporting 13 persons, which included 7 unnamed negroes. John and Daniel Gookin also patented land on the Rappahannock River along with Richard Bennett and other neighbors from the Nansemond region, although neither were resident there. [11]

John ultimately acquired 1490 acres, including 640 acres in Lower Norfolk County adjoining the Thorowgood estate in October 1641 after his marriage to Sarah Thorowgood. This land came to him for transporting 13 persons, which included 7 unnamed negroes. John and Daniel Gookin also patented land on the Rappahannock River along with Richard Bennett and other neighbors from the Nansemond region, although neither were resident there. [11]

While most government officials and Jamestown residents remained staunchly Anglican and tried to enforce adherence to the official religion, there were dissensions in Virginia as well as England in this pre-English Civil War era. The Munster area in Ireland that the Gookins came from was also known to have Puritan connections. Puritan influence in Virginia became particularly strong in Upper and Lower Norfolk and on the Eastern Shore. Richard Bennett, a friend and neighbor of the Gookins, went on to become the first Governor under the Puritan Commonwealth Era government.[14]

While most government officials and Jamestown residents remained staunchly Anglican and tried to enforce adherence to the official religion, there were dissensions in Virginia as well as England in this pre-English Civil War era. The Munster area in Ireland that the Gookins came from was also known to have Puritan connections. Puritan influence in Virginia became particularly strong in Upper and Lower Norfolk and on the Eastern Shore. Richard Bennett, a friend and neighbor of the Gookins, went on to become the first Governor under the Puritan Commonwealth Era government.[14]

As would be expected under the legal concept of coverture, John Gookin took financial responsibility for the Thorowgood estate after the marriage. He pursued debt collection and represented the Thorowgood heirs in land matters in court. After his marriage, John stepped out of his older brother’s shadow and was quickly elevated to responsible positions and accorded increased status. Thomas Willoughby and John Gookin agreed to jointly build a store at Willoughby Point for the benefit of the community. John later was designated to provide a ferry at Lynnhaven on the lands of the Thorowgood heirs. “John Gookin’s Landing,” referred to in later deeds, was on Samuel Bennett’s Creek near the site called Ferry where the Old Donation Church was built. John was reported to represent Lower Norfolk County in the Assembly in 1640. [18]

As would be expected under the legal concept of coverture, John Gookin took financial responsibility for the Thorowgood estate after the marriage. He pursued debt collection and represented the Thorowgood heirs in land matters in court. After his marriage, John stepped out of his older brother’s shadow and was quickly elevated to responsible positions and accorded increased status. Thomas Willoughby and John Gookin agreed to jointly build a store at Willoughby Point for the benefit of the community. John later was designated to provide a ferry at Lynnhaven on the lands of the Thorowgood heirs. “John Gookin’s Landing,” referred to in later deeds, was on Samuel Bennett’s Creek near the site called Ferry where the Old Donation Church was built. John was reported to represent Lower Norfolk County in the Assembly in 1640. [18]

The first jury trial in Lower Norfolk County also concerned John Gookin. Whereas fellow justices generally had no qualms about passing judgment on cases involving their peers, they decided that using a jury of 12 men provided the “most equitable way” in this matter. As noted in a prior post, the hogs belonging to Capt. John Gookin escaped their pen and damaged the corn field of his neighbor Richard Foster. As Gookin had installed sturdy fencing to try to keep his hogs in and Foster had none to keep animals out, the jury found for Gookin. At that time, planters were expected to fence in their plants if they wanted to protect them from roaming animals. [20]

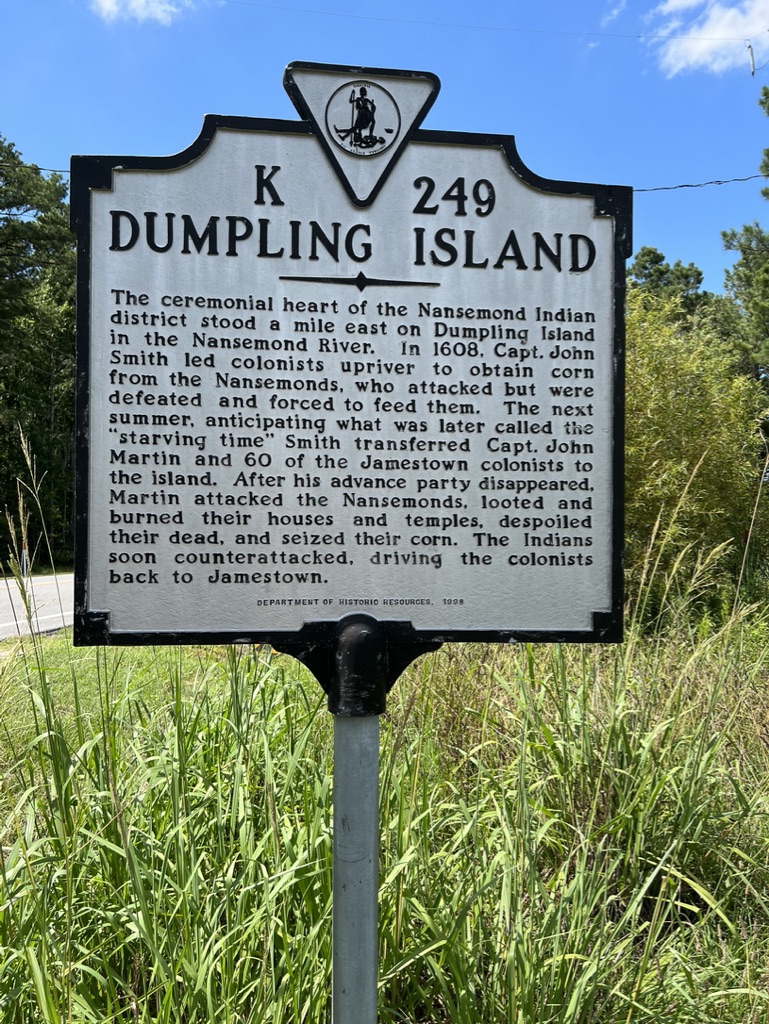

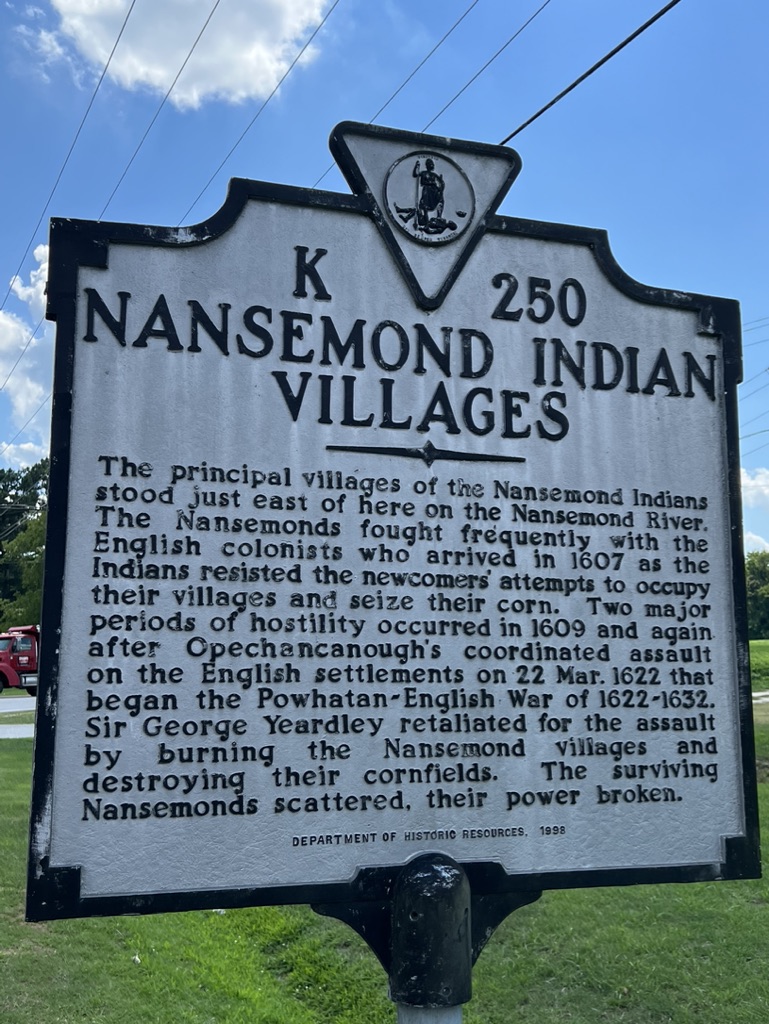

The first jury trial in Lower Norfolk County also concerned John Gookin. Whereas fellow justices generally had no qualms about passing judgment on cases involving their peers, they decided that using a jury of 12 men provided the “most equitable way” in this matter. As noted in a prior post, the hogs belonging to Capt. John Gookin escaped their pen and damaged the corn field of his neighbor Richard Foster. As Gookin had installed sturdy fencing to try to keep his hogs in and Foster had none to keep animals out, the jury found for Gookin. At that time, planters were expected to fence in their plants if they wanted to protect them from roaming animals. [20]  In the early years of the Jamestown Settlement, settlers had the expectation that the Indians would provide them corn, either by trade or force. The Nansemond tribe south of the James River under the paramount chiefdom of Powhatan first encountered Capt. John Smith and the English in 1608 when, under threat, they provided 400 baskets of corn. Although in the English perspective they parted good friends, hostilities increased as more demands were made for food and land. In 1609, Capt. John Martin was ordered to settle with his soldiers on Nansemond lands, but two of his advance soldiers went missing and were later found dead. After having been told that his men had been sacrificed and that “their brains had been cut and scraped out of their heads with mussel shells,” Capt. Martin ordered a complete destruction and desecration of the Nansemond’s sacred Dumpling Island. George Percy reported: [21]

In the early years of the Jamestown Settlement, settlers had the expectation that the Indians would provide them corn, either by trade or force. The Nansemond tribe south of the James River under the paramount chiefdom of Powhatan first encountered Capt. John Smith and the English in 1608 when, under threat, they provided 400 baskets of corn. Although in the English perspective they parted good friends, hostilities increased as more demands were made for food and land. In 1609, Capt. John Martin was ordered to settle with his soldiers on Nansemond lands, but two of his advance soldiers went missing and were later found dead. After having been told that his men had been sacrificed and that “their brains had been cut and scraped out of their heads with mussel shells,” Capt. Martin ordered a complete destruction and desecration of the Nansemond’s sacred Dumpling Island. George Percy reported: [21] Thereafter, the English and Nansemonds were avowed enemies. The Nansemonds participated in the Powhatan uprising of 1622 and attacked Daniel Gookin Sr.’s Marie’s Mount and Edward Water’s Blount Point where they kidnapped Adam Thorowgood’s master and mistress. However, Edward Bennett’s plantation bore the brunt of that Nansemond attack with 53 dead. As noted earlier, the Nansemonds continued to periodically attack settlers at Marie’s Mount. The English sought revenge, but it was not until the late 1630s that the Nansemond threat was lessened, and they started to withdraw upriver or into the southern and northwestern branches of the Nansemond River.[22]