It is common to assume the inevitability of history. After all, the story usually favors the victor. Was it really North America’s manifest destiny to be English? In the middle of the 17th century, it appeared North America could have become multi-national like Europe. Not everyone accepted that the establishment of the English colony at Jamestown, already hemmed in by the French in Canada and the Spanish in Florida, created an English claim to all the Eastern seaboard in between.

It is common to assume the inevitability of history. After all, the story usually favors the victor. Was it really North America’s manifest destiny to be English? In the middle of the 17th century, it appeared North America could have become multi-national like Europe. Not everyone accepted that the establishment of the English colony at Jamestown, already hemmed in by the French in Canada and the Spanish in Florida, created an English claim to all the Eastern seaboard in between.

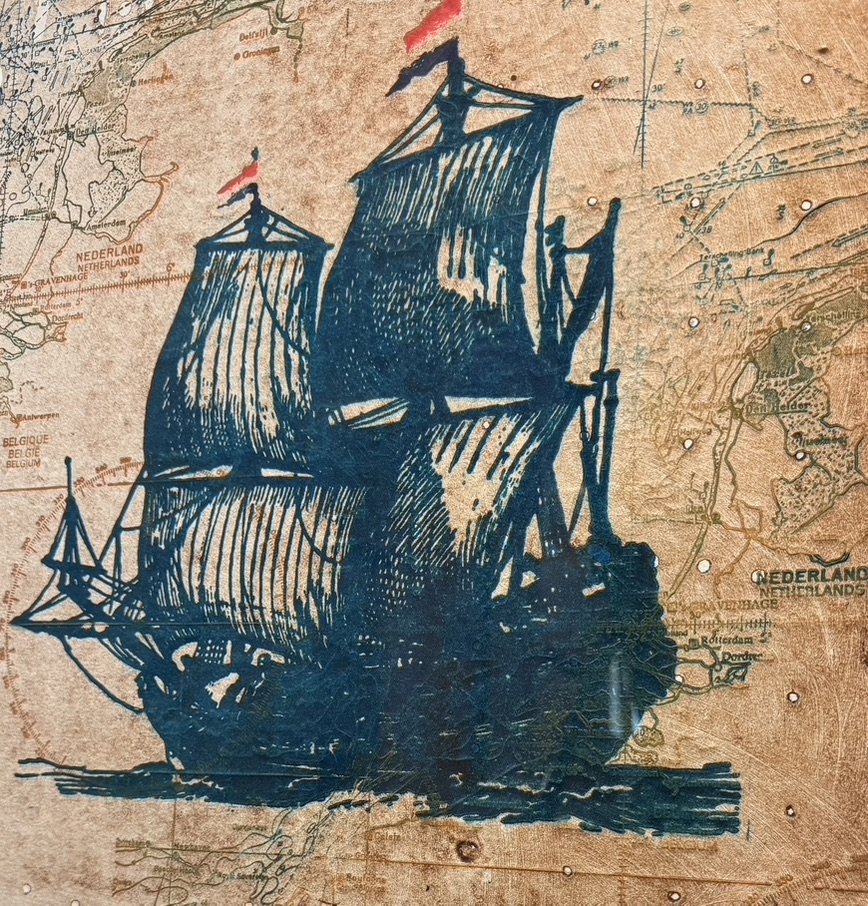

In 1609 when Jamestown was facing its Starving Time, Henry Hudson, an English explorer, accepted a commission from merchants of the Dutch East India Company of the Netherlands (which was in competition with the English East India Company) to find a northern sea route to the East Indies. On this journey, Hudson, finding the route across the Arctic still blocked with ice in May, turned his ship Halve Maeri (Half Moon) around and decided to look for a route through North America. Though not the first to find the “North River” (later renamed the Hudson River in his honor), his exploration went as far as present-day Albany. This became the basis of Dutch claims and the settlement of New Netherlands in what is now New York and New Jersey. Capt. Hudson journeyed as far south as the tip of the Chesapeake Penninsula. The following year, Hudson led an English expedition where he claimed Hudson Bay to the north for the English, after which he was set adrift by his own mutinous crew with his teenage son and 7 loyal crewmen in James Bay, never to be heard of again. [1]

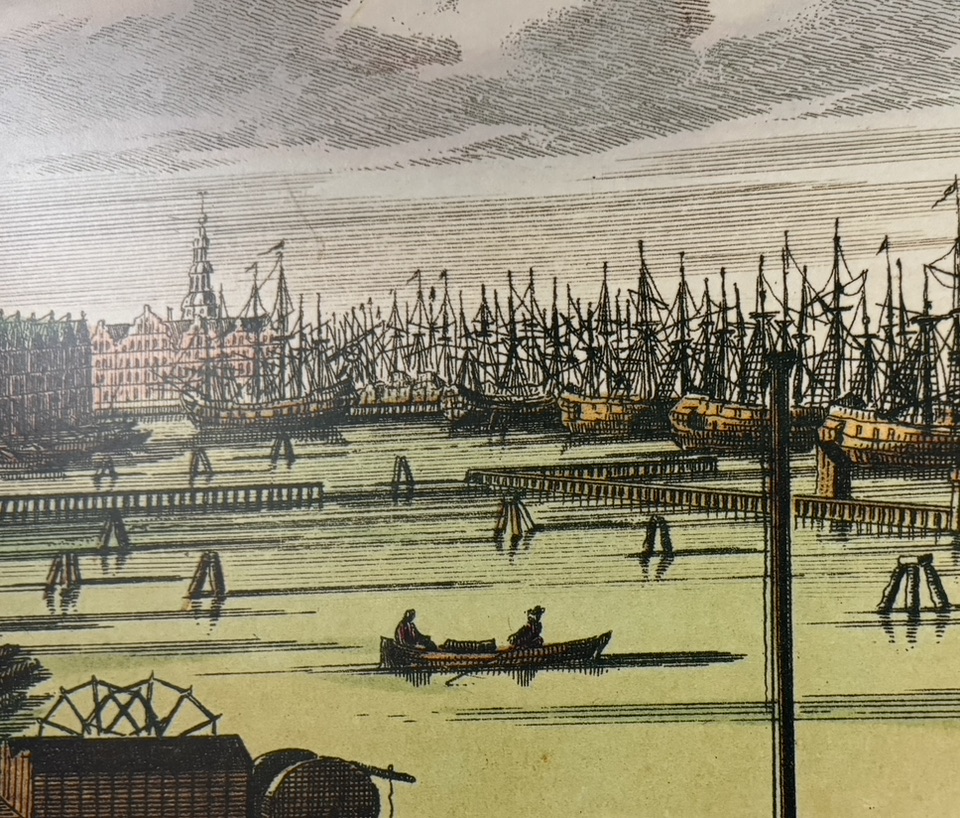

The Dutch settled New Netherlands by 1623 and founded their key city New Amsterdam (Manhattan) in 1626. Much of the wealth of the colony came from lucrative fur trading through alliances with the local indigenous tribes. Like its European namesake, New Amsterdam quickly drew settlers from a variety of countries. Alongside the Dutch lived French-speaking Huguenots, Scandinavians, Germans, and English. The Dutch were heavily involved in the slave trade, so Africans were unwillingly also part of their communities. [2]

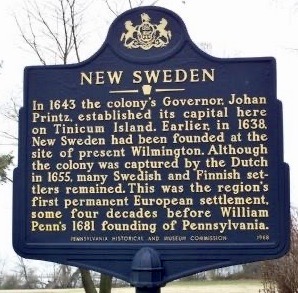

Nor were the Dutch the only Europeans settling the mid-Atlantic. Sweden, a rising European power, authorized the New Sweden Company and enticed Peter Minuit, a former governor of New Netherlands who was unhappy about his recall to Holland, to lead their first expedition to North America. They purchased land from the local Lenape chiefs and established Fort Christina in the area of today’s Wilmington, Delaware. In Anglo-centric history, William Penn is credited with founding Pennsylvania in 1681, but the Swedes were there by 1640 and had a thriving community outside today’s Philadelphia. Although there were bickering claims over the Delaware River Valley between the Dutch and Swedes, they combined forces in 1641-42 to drive out a group of English settlers trying to establish their claim there. Ultimately, the Dutch under their governor/ general Peter Stuyvesant attacked and conquered New Sweden in 1655. [3]

Nor were the Dutch the only Europeans settling the mid-Atlantic. Sweden, a rising European power, authorized the New Sweden Company and enticed Peter Minuit, a former governor of New Netherlands who was unhappy about his recall to Holland, to lead their first expedition to North America. They purchased land from the local Lenape chiefs and established Fort Christina in the area of today’s Wilmington, Delaware. In Anglo-centric history, William Penn is credited with founding Pennsylvania in 1681, but the Swedes were there by 1640 and had a thriving community outside today’s Philadelphia. Although there were bickering claims over the Delaware River Valley between the Dutch and Swedes, they combined forces in 1641-42 to drive out a group of English settlers trying to establish their claim there. Ultimately, the Dutch under their governor/ general Peter Stuyvesant attacked and conquered New Sweden in 1655. [3]

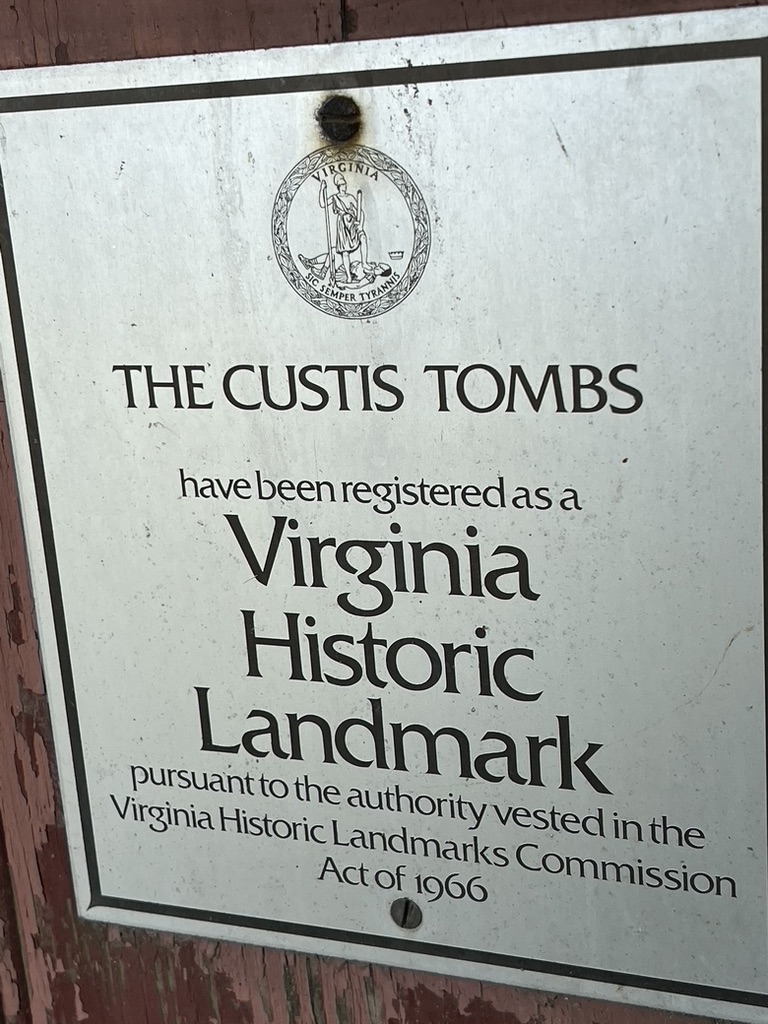

So what does this history have to do with my meandering story of the Thorowgoods in Virginia and their connections? First, one must grapple with the term “Dutch merchant.” Should that term be restricted to someone born of Dutch parents in the Netherlands who was engaged in trading goods in Dutch ships? Could it include those ex-patriots, born in England, but who migrated to the Netherlands to do business through Dutch or even English companies? What about those, like John Custis II, who were born in the Netherlands to English parents? Although John Custis II arrived in Virginia about 1651, he had to wait until 1658 before he was naturalized by an Act of the Assembly and received the rights with his Dutch-born brother William “as if they had been Englishmen born.” Were they considered “Dutch” before that? [4]

So what does this history have to do with my meandering story of the Thorowgoods in Virginia and their connections? First, one must grapple with the term “Dutch merchant.” Should that term be restricted to someone born of Dutch parents in the Netherlands who was engaged in trading goods in Dutch ships? Could it include those ex-patriots, born in England, but who migrated to the Netherlands to do business through Dutch or even English companies? What about those, like John Custis II, who were born in the Netherlands to English parents? Although John Custis II arrived in Virginia about 1651, he had to wait until 1658 before he was naturalized by an Act of the Assembly and received the rights with his Dutch-born brother William “as if they had been Englishmen born.” Were they considered “Dutch” before that? [4]

The nationality and birth place of those merchants sailing in and out of Dutch ports is not always known. The Dutch identity is further confused as “Dutch” is a language and adjective, not a country, but is usually associated with the country the Netherlands which was also known as the United Provinces, Dutch Republic, or Lowland Countries. However, that is not the same as Holland (an important province), and was distinct from Flanders or the Spanish Netherlands. Despite the confusions, much of the 17th century is viewed as the “Dutch Golden Age,” and the “Dutch” exerted great influence in the trade, arts, and politics of the time.

It was not surprising, then, that Capt. David DeVries, a noted Dutch explorer, visited Virginia in 1633. He had already had adventures in the Far East, encounters with indigenous tribes along the Delaware River, and provided service to the Dutch in New Netherlands. De Vries received a warm welcome from Virginia’s Gov. John Harvey, a former friend from their days in the East Indies. DeVries also visited Capt. Samuel Matthews, Capt. Stone, and Capt. Daniel Goegen (Gookin) along the Elizabeth River, through which he garnered valuable information about the the conditions, problems, and politics of the Virginia colony. DeVries visited Virginia thrice more in 1635, 1636, and 1643 . Daniel Gookin’s younger brother, John, with whom Daniel shared the plantation which DeVries visited, would become the second husband of Sarah Thorowgood Gookin Yeardley. [5] . See John Gookin, Sarah Thorowgood, the Nansemond Tribe, and Virginia Puritans

During this time of Dutch presence in North America, strong mercantile ties were established between the English colonies, the Netherlands, and New Netherlands. Virginians found a ready market there for their quality tobacco and enjoyed the Dutch-style “free-trade” arrangements for importing goods. During the tumultuous years of the English Civil War in the 1640s, there was relative stability in dealing with the Dutch. Over 33 Dutch ships were known to be involved in Virginia’s tobacco trade then. [6]

During this time of Dutch presence in North America, strong mercantile ties were established between the English colonies, the Netherlands, and New Netherlands. Virginians found a ready market there for their quality tobacco and enjoyed the Dutch-style “free-trade” arrangements for importing goods. During the tumultuous years of the English Civil War in the 1640s, there was relative stability in dealing with the Dutch. Over 33 Dutch ships were known to be involved in Virginia’s tobacco trade then. [6]

Argoll Yearley and his brother Francis, who had married the then twice-widowed Sarah Thorowgood Gookin, were among those Virginia planters who sold to the Dutch. A Dutch connection was not surprising in that their father, Gov. George Yeardley, had been one of the early Virginia leaders who had fought in the Low Countries war for the independence of the Dutch Republic. It was in a journey with his shipment of tobacco to Rotterdam in 1649 that Argoll Yeardley married Ann Custis, the daughter of English ex-patriots Henry and Joan Custis who managed a popular inn there. Subsequently, not only Ann, but her uncle John Custis I and brothers John Custis II, William II, and Joseph came from the Netherlands to the Eastern Shore, though John I did not settle there. [7] See Unexpected: Ann Custis Yeardley & Sarah Yeardley Part II

Argoll Yearley and his brother Francis, who had married the then twice-widowed Sarah Thorowgood Gookin, were among those Virginia planters who sold to the Dutch. A Dutch connection was not surprising in that their father, Gov. George Yeardley, had been one of the early Virginia leaders who had fought in the Low Countries war for the independence of the Dutch Republic. It was in a journey with his shipment of tobacco to Rotterdam in 1649 that Argoll Yeardley married Ann Custis, the daughter of English ex-patriots Henry and Joan Custis who managed a popular inn there. Subsequently, not only Ann, but her uncle John Custis I and brothers John Custis II, William II, and Joseph came from the Netherlands to the Eastern Shore, though John I did not settle there. [7] See Unexpected: Ann Custis Yeardley & Sarah Yeardley Part II

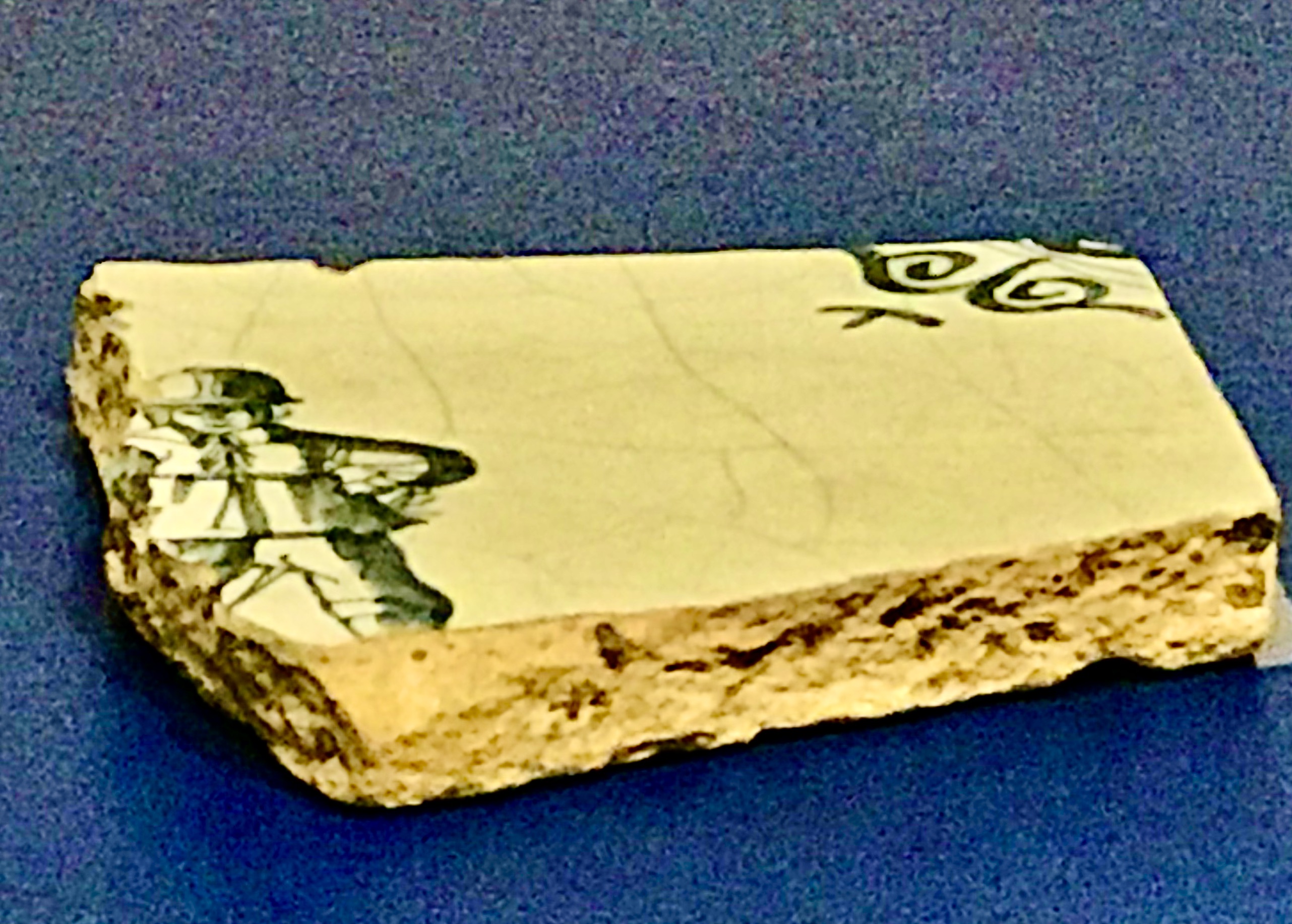

Exciting new archaeological evidence has been found of early Dutch influence and trading at Eyreville on the Cherrystone Inlet of the Eastern Shore. Having been the site of John Howe’s home in the 1630s and of the yellow-brick lined foundation of the 1657 house of William Kendall, a successful merchant and court commissioner, the artifacts reveal that this was one of the earliest sites on the Eastern Shore with substantial evidence of Dutch trade and/or possible short-term occupation. Numerous Dutch-made tobacco pipes, ceramics, and a great quantity of yellow bricks from the Netherlands have been found in the excavations. [8]

During this same time, another English merchant living in Rotterdam moved to Lower Norfolk County, Virginia, with his two sons William II and Arthur. William Moseley I and his wife Suzanne brought with them jewels from Rotterdam to use as an exchange to purchase needed livestock for their new home in Virginia.

As recorded in the Lower Norfolk Court records in November 1652, William Moseley paid the equivalent of 612 guilders for nine cattle from Francis Yeardley using an enameled gold and diamond buckle for a hat band, a gold ring set with a diamond, ruby, saphire and emerald, and a gold enameled pendant with diamonds. In a gracious letter, Suzanne Moseley wrote that “I had rather your wife should wear them than any gentlewomen I yet know in the country and … I wish Ms. Yeardley health and prosperity to wear them.” [9]

It is not surprising then that the remains of the original house built in Lower Norfolk County by Adam and Sarah Thorowgood and continually lived in by Sarah and her subsequent husbands should be replete with artifacts of Dutch goods. In a study of Dutch trade goods and ceramics in the 17th century English colonies, it was noted that “one of the largest aggregations of Dutch artifactual remains yet found archaeologically in Virginia was recovered from the so-called Chesapean site, believed to have been part of Adam Thoroughgood’s seventeenth century land holdings.” As that house burned and was abandoned in the 1650s, the artifacts are a time capsule of Dutch influence in that area. In addition, the inventory taken at Francis Yeardley’s death in 1656 included, among other items,”ten Dutch pictures.” [10] See The Material Culture of Sarah Offley Thorowgood Gookin Yeardley

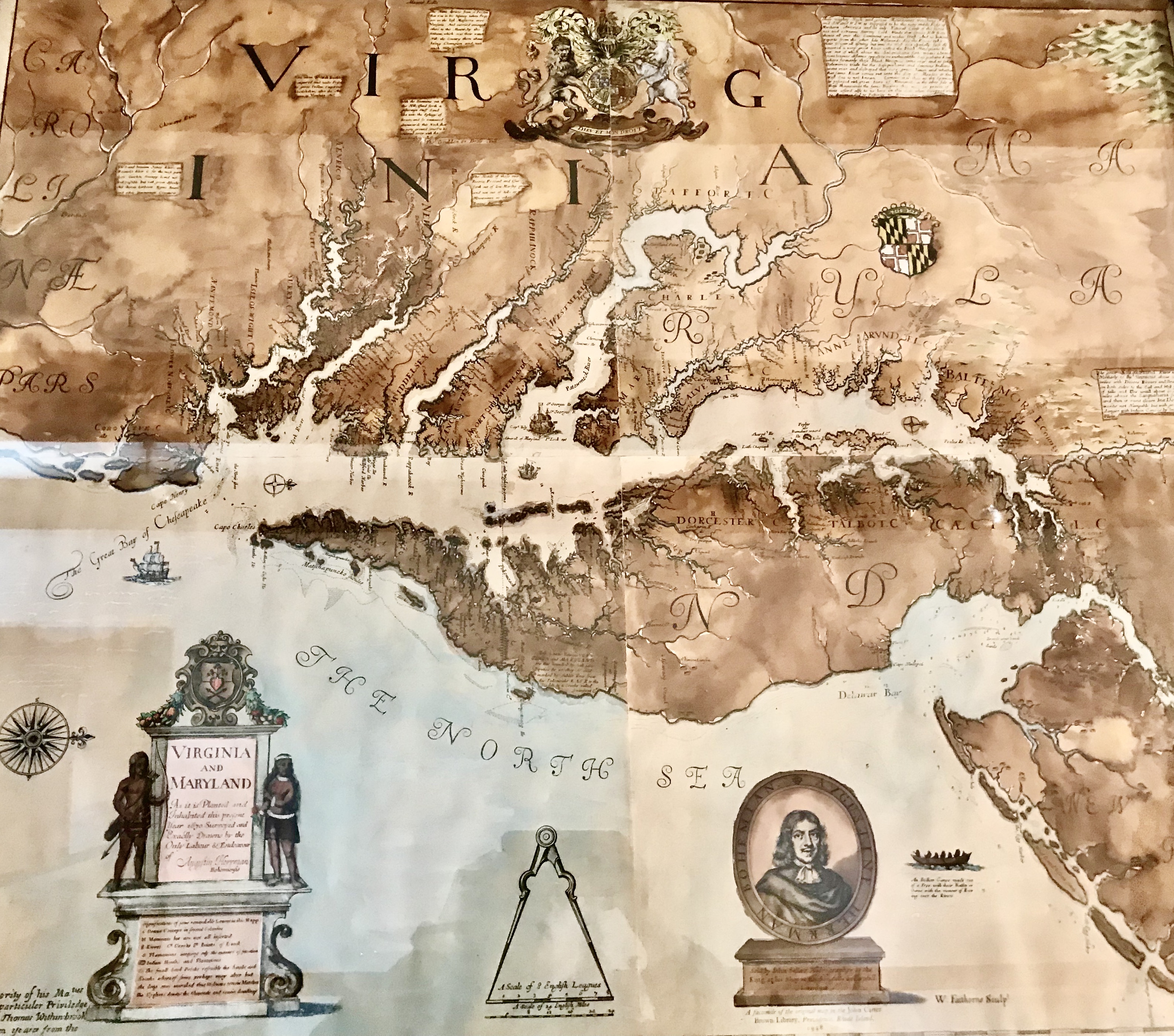

The complex interconnections are further evidenced in the experience of Augustine Herrman, a merchant born in Bohemia (now Czech Republic) who moved to Saxony (Germany), then the Netherlands, before coming to New Netherlands in 1644 as an agent for an Amsterdam merchant firm. As such, he traded with New Netherlands and New Sweden, then expanded into New England and the Chesapeake. He married Janetje Varleth of a notable Dutch merchant family and purchased land on the Eastern Shore of Virginia with the husband of his sister-in-law Ann Varleth, German-born Dr. George Hack. Hermann then expanded his networks south into Virginia’s Hampton Roads. He conducted business with the newly resident Dutch merchants John Michael and Simon Overzee, as well as John Custis, the Yeardleys, and Edmond Scarborough. Herrman also obtained land in St. Mary’s County, Maryland. As a skilled cartographer, successful merchant, and trusted negotiator, Herrman was asked to help resolve boundary disputes between the colonies. While Herrman may not have been able to satisfy all the claimants, he put his skills to creating one of best maps of the Chesapeake area of that time. [11]

However, not all were pleased with the profitable, free-flowing Dutch trade, especially in England, as the purpose of the colonies was to enrich the motherland. In an attempt to coerce and punish those colonies who remained loyal to the royalist cause, the Commonwealth Parliament in 1650 prohibited trade with the “notorious robbers and traitors ” in Antigua, Barbados, Bermuda, and Virginia and prohibited them from “any manner of commerce or traffic with any people whatsoever.” In addition, they declared that no foreign ships were allowed to trade with the English colonies without a permit from Parliament, a requirement that Parliament then turned into law in 1651 as the first of the Navigational Acts. Virginia’s Gov. Berkeley complained,

However, not all were pleased with the profitable, free-flowing Dutch trade, especially in England, as the purpose of the colonies was to enrich the motherland. In an attempt to coerce and punish those colonies who remained loyal to the royalist cause, the Commonwealth Parliament in 1650 prohibited trade with the “notorious robbers and traitors ” in Antigua, Barbados, Bermuda, and Virginia and prohibited them from “any manner of commerce or traffic with any people whatsoever.” In addition, they declared that no foreign ships were allowed to trade with the English colonies without a permit from Parliament, a requirement that Parliament then turned into law in 1651 as the first of the Navigational Acts. Virginia’s Gov. Berkeley complained,

“The Indians, God be blessed, round about us are subdued, we can only feare the Londoners, who would faine bring us to the same poverty, wherein the Dutch found and relieved us. [The Londoners] would take away the liberty of our consciences, and tongues, and our right of giving and selling our goods to whom we please.” [12]

Gov. Berkeley was dismissed; Virginia had to submit to the rule of Parliament; and the Anglo-Dutch trade suffered. Unlicensed Dutch vessels were captured in Virginia waters, and with the mounting tensions between the Netherlands and England, the first Anglo-Dutch War erupted on 30 June 1652. There were a series of naval battles as these two maritime powers fought for dominance over fishing grounds, trade in the East Indies and North America, and Caribbean possessions. It was a war that most English and Dutch colonists in America did not want, and it made Atlantic trade more risky. Northampton on the Eastern Shore even passed measures to protect Dutch traders. However, at the end of the war in 1654, enforcement of navigational restrictions was lax, especially in the outlying areas of the Eastern Shore and Lower Norfolk. The Dutch and Virginians became skilled at circumventing the laws. [13]

It was during this era that the daughters of Sarah and Adam Thorowgood were starting to come of age and be eligible for suitable marriages. In his will, Adam had given Sarah “guardianship of all of my children, until my daughters come to the age of sixteen years, and my son Adam to the age of one and twenty.” By 1649, Ann, the oldest, had married Job Chandler, an English immigrant who had lived not far from Francis Yeardley on the Eastern Shore and then apparently followed him to Lower Norfolk after Francis married Ann’s mother. Chandler purchased 240 acres there adjoining the Yeardleys. Although Chandler did not have Dutch ties himself, he quickly acquired connections. [14] See Fascinating and Formidable Sarah Offley Gookin Yeardley

It was during this era that the daughters of Sarah and Adam Thorowgood were starting to come of age and be eligible for suitable marriages. In his will, Adam had given Sarah “guardianship of all of my children, until my daughters come to the age of sixteen years, and my son Adam to the age of one and twenty.” By 1649, Ann, the oldest, had married Job Chandler, an English immigrant who had lived not far from Francis Yeardley on the Eastern Shore and then apparently followed him to Lower Norfolk after Francis married Ann’s mother. Chandler purchased 240 acres there adjoining the Yeardleys. Although Chandler did not have Dutch ties himself, he quickly acquired connections. [14] See Fascinating and Formidable Sarah Offley Gookin Yeardley

By 1646, the notable Dutch merchant, Simon (Symon) Overzee was trading for tobacco in Lower Norfolk County. In 1650, he and Francis Yeardley jointly purchased a Dutch ship, Het Wittepartt, for transporting tobacco. Job Chandler, who sometimes represented settlers in legal matters, did so for Simon Overzee in 1651. It was to this Simon Overzee that the second Thorowgood daughter, Sarah (II), was wed. Job and his wife Ann and Simon and his wife Sarah (II) soon thereafter moved to adjoining properties on Nangemy Creek in Charles County, Maryland. While in Maryland, Simon Overzee and Augustine Hermann set up a “firme Corpartnership and Common fellowship of trade and traffique for three yeares.” Even after the Overzees moved to the St. John’s house in St . Mary’s County, Maryland, he still continued to be actively involved in commerce in Lower Norfolk County and the Eastern Shore. It was at St. John’s that the tragic death of enslaved Antonio occurred. [15]

Elizabeth Thorowgood, Adam and Sarah’s third daughter, married John Michael (Machelle, Michielsz), a Dutch merchant from Graft, Holland, who was trading on the Eastern Shore by 1652. Michael was often asked to act as an attorney or representative in the affairs and disputes of other merchants from Amsterdam, New England, and Virginia. Still, in 1663, John Michael’s appointment to the Northampton Court was rescinded for a couple of months until he could provide proof that he was not an alien, but had been naturalized an English citizen. Margaret, a daughter of John and Elizabeth Thorowgood Michael, was the first wife of John Custis III and lived at Hunger’s Creek (Wilsonia) on the Eastern Shore. John Custis IV was one of her sons. [16]

Sarah Thorowgood Gookin Yeardley’s fourth daughter, Mary Gookin, was born from her second marriage. Mary would have only been about 15 years old when her mother died in 1657. However, the Dutch connection was maintained in her marriage as well. Mary married William Moseley II who had come with his parents from Rotterdam when they exchanged jewels for cattle with the Yeardleys in Lower Norfolk County. [17]

Notably, there was one Thorowgood groom, Adam Thorowgood II. He must have been quite young when his father Adam Thorowgood died in 1640, as he had not yet obtained his majority at the death of his mother in 1657. He, therefore, selected his brother-in-law Simon Overzee as his guardian. Nor did Adam II look much outside the family network when it was time to marry. He selected Frances Yeardley, the daughter of Argoll and his first wife. Although connected through marriages, they were not blood relations. Frances would have grown up under the influence of her step-mother, Ann Custis Yeardley. [18]

These marriages and families each have their own complex stories which have only been introduced in this post. Clearly, Dutch connections were part of their heritage. Their stories and that of the evolving colonial experience will be expanded in my subsequent posts.

In February 1657, Gov. Peter Stuyvesant and his New Netherlands Council called for a day of thanksgiving. The Anglo-Dutch war had ended, relations with the local tribes had improved, prosperity was increasing, settlement was expanding, and they had conquered New Sweden. Despite England’s attempts to regulate colonial trade, Dutch merchants were still doing a good, if illicit, business with the colonies. The Dutch had held their North American claim for nearly 50 years and anticipated that they were there to stay. [19]

In February 1657, Gov. Peter Stuyvesant and his New Netherlands Council called for a day of thanksgiving. The Anglo-Dutch war had ended, relations with the local tribes had improved, prosperity was increasing, settlement was expanding, and they had conquered New Sweden. Despite England’s attempts to regulate colonial trade, Dutch merchants were still doing a good, if illicit, business with the colonies. The Dutch had held their North American claim for nearly 50 years and anticipated that they were there to stay. [19]

However, in 1660 increased tensions between their motherlands led Gov. Stuyvesant and Gov. Berkeley, who had been reappointed with the Restoration, to create their own “Articles of amitie and commerce” to facilitate and protect trade between their colonies. However, Charles II increased trade restrictions and enforcement, and soon the Anglo-Dutch wars resumed. After an English fleet arrived at New Amsterdam, Peter Stuyvesant was forced to surrender on September 29, 1664. [20]

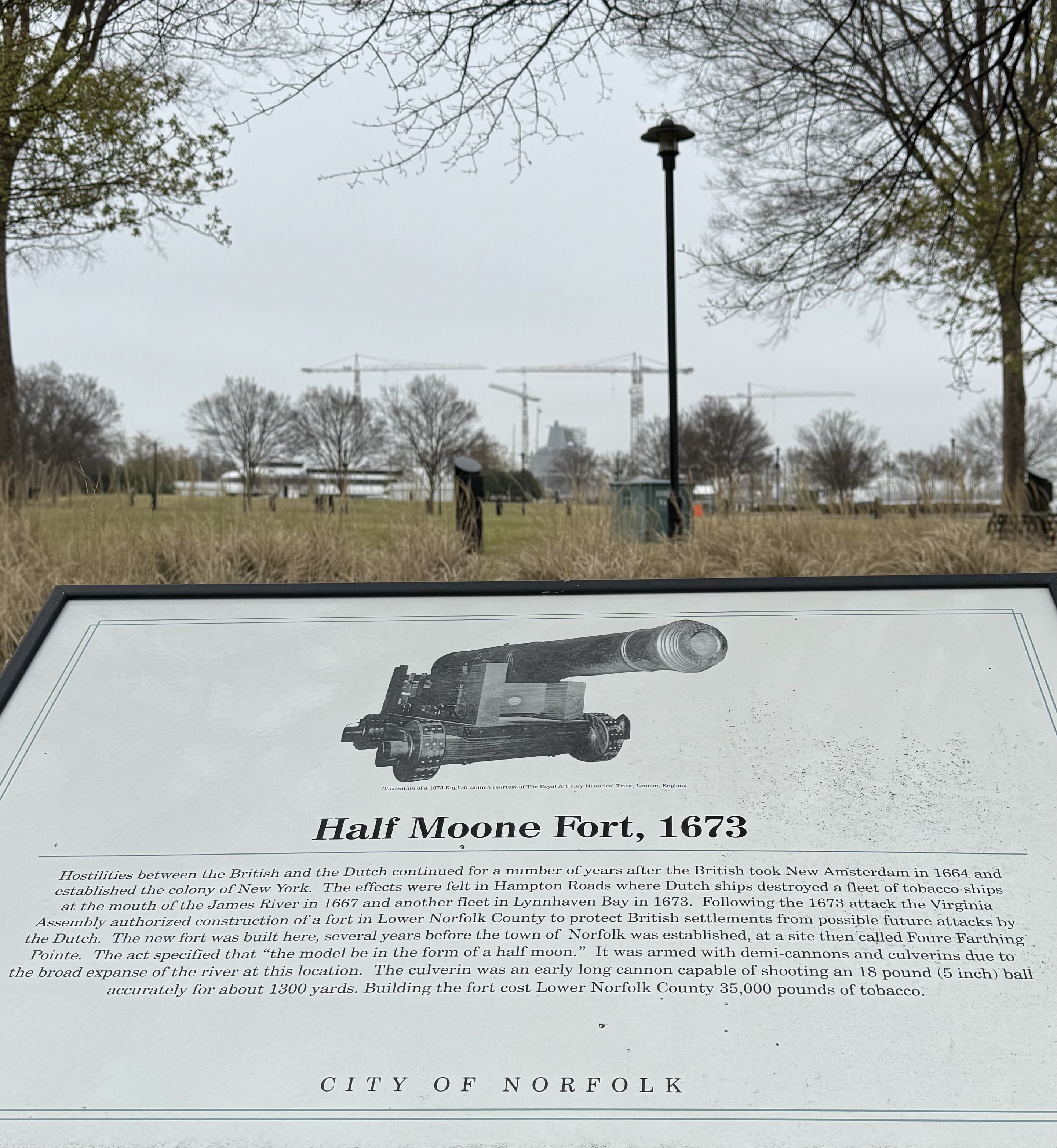

When the first Jamestown settlers built their fort, they installed cannon facing the James River, expecting to fight the Spanish. However, the Spanish never attacked. Despite years of friendship and mutually beneficial trade, it was the Dutch who ended up attacking Virginia. Dutch ships destroyed a fleet of Virginia tobacco ships at the mouth of the James River in 1667, and attacked ships in the Lynhaven Bay in Lower Norfolk County in 1673. In response, Virginia built the Half Moon Fort on the Elizabeth River (where Norfolk now stands) to protect themselves against further attacks. By then, England had aggressively captured New Netherlands, broken Dutch sea dominance, and established control over the North American eastern seaboard. Colonial resentment over England’s trade restrictions, however, continued to simmer until the Revolution a century later. [21]

When the first Jamestown settlers built their fort, they installed cannon facing the James River, expecting to fight the Spanish. However, the Spanish never attacked. Despite years of friendship and mutually beneficial trade, it was the Dutch who ended up attacking Virginia. Dutch ships destroyed a fleet of Virginia tobacco ships at the mouth of the James River in 1667, and attacked ships in the Lynhaven Bay in Lower Norfolk County in 1673. In response, Virginia built the Half Moon Fort on the Elizabeth River (where Norfolk now stands) to protect themselves against further attacks. By then, England had aggressively captured New Netherlands, broken Dutch sea dominance, and established control over the North American eastern seaboard. Colonial resentment over England’s trade restrictions, however, continued to simmer until the Revolution a century later. [21]

Special Thanks to Jenean Hall, Eastern Shore historian and author, for helping me locate and understand the Eastern Shore connections.

Footnotes:

[1] Jacobs, Jaap, The Colony of New Netherland: A Dutch Settlement in Seventeenth-Century America (Ithaca, New York: Cornell University, 2009), 21-22. “Henry Hudson,” accessed online on 4/3/2024 from Wikipedia at en.wikipedia.org/ wiki/Henry_ Hudson.

[2] Jacobs, 30-31. Romney, Susanah Shaw, New Netherland Connections: Intimate Networks and Atlantic Ties in Seventeenth-Century America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014), 13.

[3] Waldron, Richard, “New Sweden: An Interpretation,” in Revisiting New Netherland: Perspectives on Early Dutch America, ed. Joyce D. Goodfriend (Leiden: Brill, 2005), 73-75. Covart, Elizabeth, “New Sweden: A Brief History,” Penn State University Libraries (2004) accessed online on 3/15/2024 at Unearthing Past Student Research.

[4] Lynch, James B., Jr., The Custis Chronicles: The Years of Migration (Camden, Maine: Picton Press, 1992), 159-160.

[5] Parr, Charles McKew, The Voyages of David DeVries (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Co., 1969), 233; 236-238, 242-250. Lounsbury, Carl R., ” Golden Quarter” in The Material World of Eyre Hall: Four Centuries of Chesapeake History, ed. Carl R. Lounsbury (Baltimore: Maryland Center for History and Culture, 2021), 36. McCartney, Martha W. Jamestown People to 1800 (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company, 2012), 175-176

[6] Truxes, Thomas M., The Overseas Trade of British America (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2021), 95-97. Lounsbury, 36-37. Jacobs, 142. Waldron, 104-105. Pagan, John R., “Dutch Maritime and Commercial Activity in Mid-Seventeenth-Century Virginia,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, 90:4 (October 1982), 488-491.

[7] Lynch, 137-169. Lounsbury, 37. McCartney, 131-133, 462-463. Leath, Robert A. “Dutch Trade and Its Influence on Seventeenth-Century Chesapeake Furniture, ” accessed online on 3/12/2024 through Chipstone Foundation https://chipstone.org/content.php/24/Copyright. (1993-2016). Hall, Jenean, Another Day: More Stories from the Early Colonial Records of Virginia’s Eastern Shore (Kwe Publishing, 2023), 100.

[8] “Eyreville” National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (VLR Listed 6/15/2023; NRHP Listed 3/18/2024) Site VDHR #065-5126/44NH0507: Section 7: 27-30; Section 8: 39.

[9] “Virginia Council Journals” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, 35 (1927), 50-51. Brayton, John A., Transciption of Lower Norfolk County, Virginia Records Record Book “C” 16651-1656 Volume Two (Baltimore: Clearfield Company, 2010), 49-51 (24b). McCartney, 291.

[10] Wilcoxen, Charlotte, Dutch Trade and Ceramics in America in the Seventeenth Century (Albany: Albany Institute of History and Art, 1987), 21. Brayton, 435.

[11] Lounsbury, 38. Koot, Christian J., A Biography of a Map in Motion: Augustine Herrman’s Chesapeake (New York: New York University Press, 2018) 15-18, 25, 39-40. Whitelaw, Ralph T., Virginia’s Eastern Shore: A History of Northampton and Accomack Counties (Richmond, Virginia Historical Society, 1951), 687, 694-696]

[12] Pagan, 494.

[13] Truxes, 95. Pagan, 497. Jones, J.R., The Anglo-Dutch Wars of the Seventeenth Century (London: Longman Group, 1996), 11-12. Hainsworth, Roger and Christine Churches, The Anglo-Dutch Naval Wars 1652-1674 (Gloucestershire, England: Sutton Publishing, 1998), 16-18. Wise, Jennings Cropper, Ye Kingdome of Accawmacke of the Eastern Shore or Virginia in the Seventeenth Century (Richmond, The Bell Book and Stationary Co., 1911), 71. Leath (online).

[14]“The Thorowgood Family of Princess Anne County, Va, ” The Richmond Standard, 4: no. 13 (26 November 1882). Chandler, Joseph Barron, “Chandlers to Virginia 1607-1700, Part II” Tidewater Virginia Families: A Magazine of History and Genealogy, 12:3 (November/December 2003), 187-193.

[15] Jones, Jacqueline, A Dreadful Deceit (New York: Basic Books, 2013), 13-17. Koot, 40. Parramore, Thomas C., Norfolk: The First Four Centuries (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1994), 37-39.

[16] Koot, 39. Mackey, Howard and Marlene A. Groves, Northhampton County Virginia Record Book Court Cases Vol.8 1637-1664 (Rockport, Maine: Picton Press, 2002), 330, 341, 339. Whitelaw, 107-117. Hall, Jenean, unpublished papers on John Michael, 2023.

[17] McCartney, 291.

[18] McCartney, 403, 463 . Brayton, John A., Transcription of Lower Norfolk County, Virginia Records Wills and Deeds, Book “D,” 1656-1666 Volume One (Memphis: Cain Lithographers, 2007), 108.

[19] Romney 9-12.

[20] Pagan, 497. Jones, J. R., 3-10.

[21] Jones, J.R., 217-224. Pagan, 500-501. Quarstein, John V.,”Hampton Roads Invaded: The Anglo-Dutch Naval Wars” published online by The Mariners’ Museum and Park, Yorktown, Virginia on Oct 15, 2020. Accessed online 9/13/2023 at http://www.marinersmuseum.org.