Round 1: Win for the Council

On the night of April 27, 1635, a messenger arrived at the Jamestown home of Sir John Harvey, the temperamental Governor of Virginia, with news of mutinous secret meetings to circulate a petition of grievances against the Governor. The igniting spark was that Harvey had not forwarded to the King the original reply of the councillors and burgesses regarding the King’s proposed tobacco plan. Angry and suspicious, Harvey had his Secretary John Kemp roused that night to arrest three leaders of the protest (Francis Pott, Capt. Martin, and William English) and to summon his Council to consider trying them under martial law.

On the night of April 27, 1635, a messenger arrived at the Jamestown home of Sir John Harvey, the temperamental Governor of Virginia, with news of mutinous secret meetings to circulate a petition of grievances against the Governor. The igniting spark was that Harvey had not forwarded to the King the original reply of the councillors and burgesses regarding the King’s proposed tobacco plan. Angry and suspicious, Harvey had his Secretary John Kemp roused that night to arrest three leaders of the protest (Francis Pott, Capt. Martin, and William English) and to summon his Council to consider trying them under martial law.

When the Council met on April 29, most of them preferred to decide the matter as a civil case, but the Governor demanded each councillor write without discussion what should be the plight of those arrested, which several refused to do. The following day when George Menefie, a usually moderate councillor, answered Harvey’s question about the colonists’ complaints, the Governor decided Menefie must be complicit and struck him on the shoulder declaring, “I arrest you on suspicion of treason.” At that moment, Councillors Samuel Matthews and John Utie jumped up, seized the Governor, and placed him under house arrest. At a signal, Dr. John Potts, brother of arrested Francis Potts and himself a former interim Governor, had Harvey’s house where they were meeting surrounded by 40-50 armed musketeers “at the ready.” [1]

Or something like that. Governor Harvey wrote his version; Samuel Matthews prepared his own statement; Secretary Kemp sent a version to the Privy Council, and Sir John Zouch’s son sent his recollection to his father in England. Matthews complained: “the Governor usurped the whole power, in all causes without any respect to the votes of the council.” The Governor countered: “Instead of giving me assistance, they stand contesting and disputing my authority, averring that I can do nothing but what they shall advise me, and that my power extendeth no further than a bare casting voice.” There were small variances in the accounts, but the basic facts were undisputed. [2]

Or something like that. Governor Harvey wrote his version; Samuel Matthews prepared his own statement; Secretary Kemp sent a version to the Privy Council, and Sir John Zouch’s son sent his recollection to his father in England. Matthews complained: “the Governor usurped the whole power, in all causes without any respect to the votes of the council.” The Governor countered: “Instead of giving me assistance, they stand contesting and disputing my authority, averring that I can do nothing but what they shall advise me, and that my power extendeth no further than a bare casting voice.” There were small variances in the accounts, but the basic facts were undisputed. [2]

The incident was about the division of power much more than an unsent letter. With no granted authority, the Governor’s Council “thrust out” their governor and forced him to return to England to appear before the Privy Council. The Virginia Council then selected one of their own, John West, as the temporary governor. After some maneuvering, John Harvey returned to England on May 23, 1635 with two of his accusers. It was a successful coup and America’s first rebellion against royal authority, but the conflict was not yet over. [3]

Round 2: Win for the Governor

Sir John Harvey won Round 2 on January 18, 1636-7, when he landed back in Virginia as the recommissioned Governor of His Majesty, King Charles I. Although Harvey had had to pay for the sailors, supplies, and repairs to the leaky Black George to return, he had gotten his payback in having the accusers who had accompanied him to London themselves arrested before they could take action against him. When he appeared before the Privy Council in December, they found the councillor’s charges against him to be groundless. Gov. Harvey returned to Virginia not only with his commission but with warrants for Councillors Samuel Matthews, John Utie, William Pierce, John West, and George Menefie to answer charges in England. [4]

With his fiercest opponents gone, Gov. Harvey convened a much calmer General Assembly with his modified council and the elected burgesses on February 20, 1636-7. Harvey’s reconstituted council included those more favorable to him: Secretary Richard Kemp, George Donne, Thomas Purifye (or Purfoy), Henry Browne of the Four Mile Tree property, Francis Hooke, and four newly appointed Councillors: Adam Thorowgood, William Brocas, Francis Hooke, and John Hobson. George Donne, son of the poet John Donne, wrote a lengthy defense of Harvey when he was in England. [5]

This second term of Governor Harvey was less contentious, but, unfortunately, not well documented. There is an extant letter dated February 20, 1637-38 signed by Governor Harvey, Thorowgood, Brown, and Brocas to the King supporting the request for increased income for Secretary Richard Kemp. In the Assembly which met March-April of that year, the Burgesses continued to oppose the King’s proposed tobacco policy and requested free trade. However, they and the Govenor exchanged letters this time rather than blows. Repairs were ordered for the Point Comfort Fort, and construction of the first statehouse was approved. Yet, the prior power struggle was still not over. [6]

Prelude to the Fight

What had led to the literal stand off between Harvey and his Council? John Harvey had been a successful, though temperamental, sea captain who was awarded a tract of land by the Virginia Company in 1622 for transporting persons to the Colony, and he had invested in potash production there. In 1623, Harvey was appointed by King James I to chair the royal commission consisting of John Pory, Abraham Piersey, and Samuel Matthews (all influential in Jamestown) to ascertain and report on the conditions in the Colony after the recent Powhatan Uprising. While in Virginia, the colonists were suspicious of the commission, and Harvey garnered a bad reputation from his autocratic and threatening behavior with his ship’s crew as well as Virginia planters.

What had led to the literal stand off between Harvey and his Council? John Harvey had been a successful, though temperamental, sea captain who was awarded a tract of land by the Virginia Company in 1622 for transporting persons to the Colony, and he had invested in potash production there. In 1623, Harvey was appointed by King James I to chair the royal commission consisting of John Pory, Abraham Piersey, and Samuel Matthews (all influential in Jamestown) to ascertain and report on the conditions in the Colony after the recent Powhatan Uprising. While in Virginia, the colonists were suspicious of the commission, and Harvey garnered a bad reputation from his autocratic and threatening behavior with his ship’s crew as well as Virginia planters.

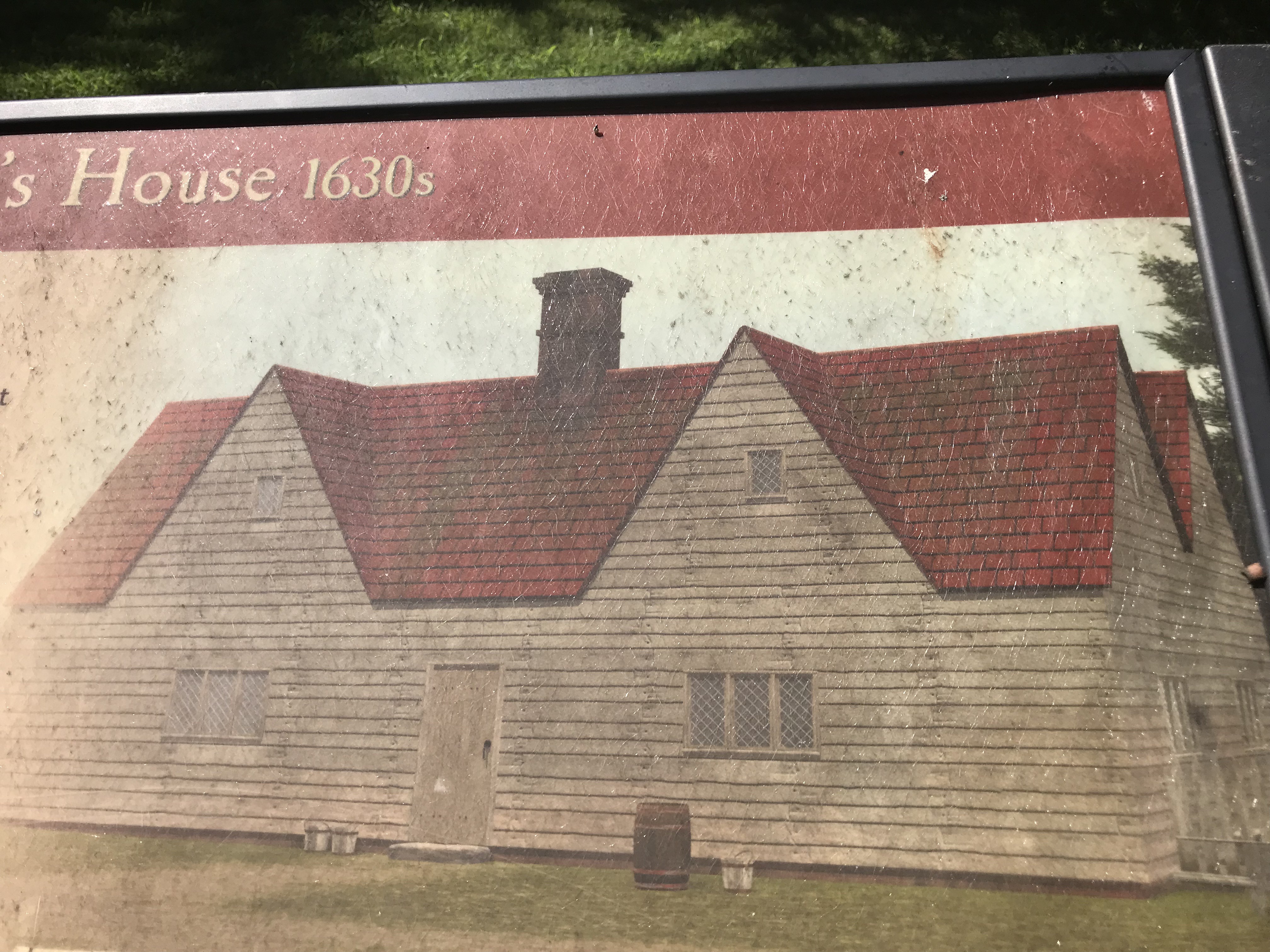

The commission reported to the Privy Council that the Colony was in better shape than expected, but was sorely lacking in needed arms and munitions. However, it was severely critical of the leadership of the Virginia Company. King James decided in 1624 to revoke the charter of the Virginia Company and make the settlement a royal colony. Many colonists opposed this and were fearful it would result in confiscation and reallocation of their land as the English had done in Ireland. For his part, John Harvey was knighted and designated to be the governor in 1628 after the death of Governor George Yeardley. [7]

While John Harvey had been an effective, if difficult, sea captain, he was poorly suited to run a “ship of state.” He did not come to Virginia as governor until 1630 when he replaced Dr. John Potts, the interim governor who was indicted for stealing cattle. Although Harvey had worked with Matthews on the commission, as governor, he soon ran afoul of the powerful coalition of councillors led by Samuel Matthews and William Claiborne. As important and wealthy tobacco planters and merchants, they had been working with influential London merchants to have the Virginia Company rechartered which Harvey opposed. Harvey’s negotiated peace with the Powhatans also displeased some councillors who wanted to take a harder stand.

While John Harvey had been an effective, if difficult, sea captain, he was poorly suited to run a “ship of state.” He did not come to Virginia as governor until 1630 when he replaced Dr. John Potts, the interim governor who was indicted for stealing cattle. Although Harvey had worked with Matthews on the commission, as governor, he soon ran afoul of the powerful coalition of councillors led by Samuel Matthews and William Claiborne. As important and wealthy tobacco planters and merchants, they had been working with influential London merchants to have the Virginia Company rechartered which Harvey opposed. Harvey’s negotiated peace with the Powhatans also displeased some councillors who wanted to take a harder stand.

Virginians were also strongly opposed to the charter given Lord Baltimore for the Colony of Maryland in which they were not only given land that had earlier been part of Virginia but also allowed Catholic settlers. They were upset when Harvey recognized Maryland’s royal charter and provided assistance to their colonists. Harvey also did not support his own councillor, William Claiborne, on his claims to Kent Island in the Chesapeake Bay against Maryland. Claiborne was absent from the “thrusting out” council meeting which fortunately kept him from being indicted with the others. Then there were the infamous temper tantrums of the Governor, such as when he took offense and bashed out several teeth of council member Richard Stephens with a cudgel and then justified his action because it was done in private and not in an official meeting. Remarkably, Harvey later married Stephen’s widow. [8]

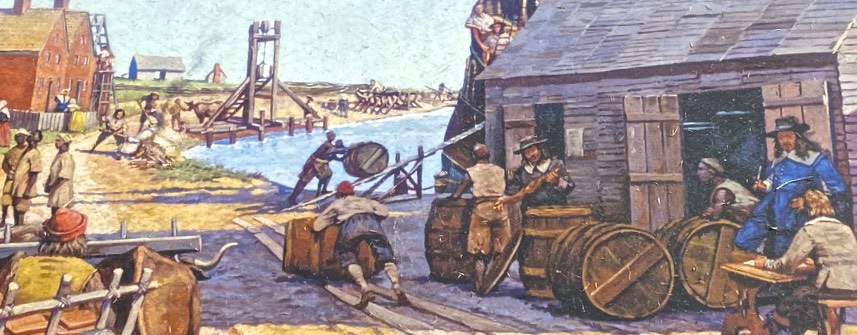

Current historians recognize, though, that there were good projects and policies implemented during Harvey’s term which are often overlooked because of his personality and conflicts. Working together, the Assembly and Governor created the eight county shires, established local courts, completed the palisade across the Middle Penninsula to protect settlers and enclose livestock, increased production of grain, and diversified endeavors. In 1633, Virginia was able to provide for their doubling population as well as send between 5,000- 10,000 bushels of grain to New England. [9]

Current historians recognize, though, that there were good projects and policies implemented during Harvey’s term which are often overlooked because of his personality and conflicts. Working together, the Assembly and Governor created the eight county shires, established local courts, completed the palisade across the Middle Penninsula to protect settlers and enclose livestock, increased production of grain, and diversified endeavors. In 1633, Virginia was able to provide for their doubling population as well as send between 5,000- 10,000 bushels of grain to New England. [9]

Was It The King’s Fault?

A leader bears responsibility for selecting good subordinates, and John Harvey had clearly shown that he did not have the appropriate temperament to lead the Colony. However, many Virginians would not have been satisfied even if Harvey had been pleasant, because he was dutifully supporting the king’s unpopular initiatives. When Charles I became king after his father had dissolved the Virginia Company, there was great anxiety as to what it would mean to be a royal colony which Charles did not clarify for years. During this time, King Charles asserted he could rule on his own and disbanded the English Parliament for 11 years, leaving Virginians to wonder if they would be allowed to keep their lands and representative government. It was, after all, Charles who had given Virginia land to Maryland. [10]

Another concern was how power would be balanced and decisions shared between the king, his governor, the assembly, and the local colonists. Neither the King nor Governor Harvey tolerated dissent. Even the spark that ignited the incident was of the King’s making. His proposal to create a royal monopoly over the tobacco trade united the factions of Virginia tobacco growers in opposition. To exert his royal privilege, King Charles did recommission Governor Harvey, but he did not give Harvey much support or seek to change or clarify the troubling situation in Virginia. The King insisted that Governor Harvey had to return “even if for only one day,” but delays in receiving his owed salary forced Harvey to have to borrow from those he was supposed to rule. [11]

Accepting a Council Appointment

There was no position in Virginia, except governor, with more power and prestige than that of a member of the governor’s council. Councillors were appointed and could serve for life, not elected like Burgesses. They had executive powers as advisors to the Governor, legislative powers as members of the unicameral General Assembly, and judicial powers as justices of the colony’s General Court. While they were supposed to act for the welfare of all Virginians, they were sometimes known to promote their own interests and those of their wealthy friends. [12]

Appointing Adam Thorowgood upon Harvey’s return in 1637 would have been a logical and wise choice. With his brother, Sir John Thorowgood of Kensington, serving in the court of Charles I and his vast land grant in Virginia coming at the recommendation of the King’s Privy Council in 1634, Adam Thorowgood had influential connections in both the Colony and England which could be helpful to Harvey. While himself a merchant-planter, Thorowgood had not closely aligned himself with the Matthews-Claiborne faction. Thorowgood supported free trade with the Dutch and diversified his land use, raising livestock as well as tobacco. However, he was not fully aligned with Harvey’s agenda. Adam was of Puritan background and likely would have opposed taking land assigned to Virginia to create the Catholic haven of Maryland. Still, he had not embroiled himself directly in the conflicts with Harvey and had served under him previously as a Burgess. Adam’s rapid rise in 15 years from an indentured servant to councillor indicates he was probably persistent, but also pragmatic.

Thorowgood likely added a stabilizing influence on the troubled Council. Adam would have been familiar with those on the Council, particularly his prior neighbor on the Back River, Thomas Purifye, with whom he had served as both a burgess and a justice from lower (eastern) Elizabeth City. Purifye along with Henry Browne were known to usually be supporters of Governor Harvey. This reconstituted council, though, soon had more vacancies as Purifye, Hooke, and Thorowgood all died by 1640. Adam Thorowgood did not have much opportunity to make his impact as a councillor. [13]

Round 3 and The Knockout: The Dismissal of Governor Harvey

Governor Harvey probably felt justified and secure in sending his rebellious councillors to England, but it ultimately worked against him. He had alienated many people and had few friends he could count on to pursue his case there. On the other hand, Matthews, Claiborne, Potts, and others aligned with them had close relations with the wealthy and influential London tobacco merchants and those formerly connected with the Virginia Company. Rather than facing condemnation and dismissal, they managed to convince the Privy Council and King that Governor Harvey should be replaced by a former governor, Francis Wyatt.

Governor Harvey probably felt justified and secure in sending his rebellious councillors to England, but it ultimately worked against him. He had alienated many people and had few friends he could count on to pursue his case there. On the other hand, Matthews, Claiborne, Potts, and others aligned with them had close relations with the wealthy and influential London tobacco merchants and those formerly connected with the Virginia Company. Rather than facing condemnation and dismissal, they managed to convince the Privy Council and King that Governor Harvey should be replaced by a former governor, Francis Wyatt.

In November 1639, Sir John Harvey was dismissed. He stayed in Virginia into 1640, but found himself “badly in debt and widely despised.” He returned to England and struggled to collect debts owed him in Virginia and England. Sir John Harvey died in poverty and disgrace in 1650. On the other hand, Samuel Matthews and the others were not convicted in England and were reinstated to their powerful places on the Council when they returned to Virginia. [14]

In November 1639, Sir John Harvey was dismissed. He stayed in Virginia into 1640, but found himself “badly in debt and widely despised.” He returned to England and struggled to collect debts owed him in Virginia and England. Sir John Harvey died in poverty and disgrace in 1650. On the other hand, Samuel Matthews and the others were not convicted in England and were reinstated to their powerful places on the Council when they returned to Virginia. [14]

After the Fight

Gov. Francis Wyatt was both cautious and conciliatory toward the Council in his second term. However, many Virginia governors after Harvey also experienced power struggles with their councillors. In 1694, Reverend James Blair, the commissary of the Bishop of London for Virginia, was appointed to the Council of Governor Edmund Andros. While Andros was not “thrust out” like Harvey, Blair and his faction of councillors successfully lobbied in London for his dismissal, and Andros resigned in 1699. Nor did they like Governor Nicholson who succeeded Andros, and they got Nicholson dismissed in 1705. Despite Lt. Governor Alexander Spotswood’s success in containing piracy and expanding westward, the Council under Blair also contended against him and had him unwillingly removed in 1722. Finally, Governor Dunmore and his family fled Williamsburg in the middle of the night in June 1775, ending the rule of British governors in Virginia.[15]

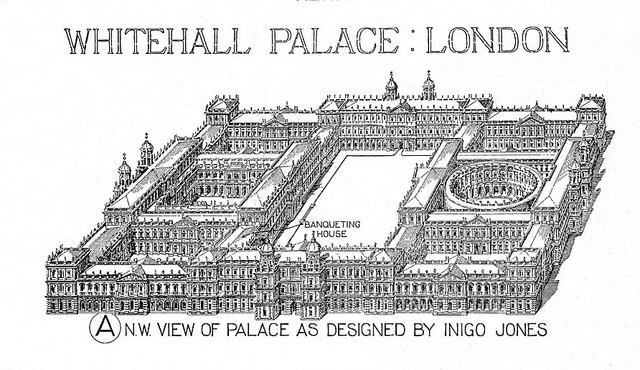

Governor Harvey’s difficulty with governing did not happen in isolation. In the following decade, England itself was engulfed in Civil War over the power struggle between Parliament and King. Ultimately, King Charles I was not only “thrust out,” but beheaded. While the ousting of Governor Harvey was not a populist movement like the later Bacon’s Rebellion in 1676, it was clear and early evidence of the developing desire of the English colonists for self-determination and participatory rule.[16]

Next Post: The Death Of Adam Thorowgood

Footnotes:

[1] Billings, Warren M., The Old Dominion in the Seventeenth Century (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007), 314-318. Neill, Edward D., Virginia Carolorum: The Colony Under the Rule of Charles the First and Second (Albany: Joel Munsell’s Sons, 1886; reprinted facsimile), 114-117. Tartar, Brent, “Sir John Harvey: Royal Governor of Virginia 1628-1639,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, 125:1 (2015), 9-22. Thornton, J. Mills, III, “The Thrusting Out of Governor Harvey: A Seventeenth Century Rebellion,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, 76:1 (January 1968), 11-12.

[2] Billings, Old Dominion, 310-318.

[3] Thornton, 26-27. Haskell, Alexander B., For God, King, & People: Forging Commonwealth Bonds in Renaissance Virginia (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017), 268-269.

[4] Billings, Old Dominion, 298-299. Tarter, 23-24.

[5] Tarter, 24- 26.

[6] Neill, 138-139. Virginia General Assembly, Journals of the House of Burgesses of Virginia, Volume 1, McIlwaine, Henry Read and John Pendleton Kennedy, eds. (Princeton: Princeton University, 1915; digitized by Library of Virginia 1/27/2009), 57-65. Accessed online. “Virginia in 1637-8,”Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, IX (June 1902), 408-409.

[7] Billings, Warren M., A Little Parliament: The Virginia General Assembly in the Seventeenth Century (Richmond: Library of Virginia, 2004), 71-72. McCartney, Martha W., Jamestown People to 1800 (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company, 2012), 197-198. Tarter, 3-7. Thornton, 13-17.

[8] Billings, Little Parliament, 92-93. Tarter, 11-12. Thornton, 19-24. McCartney, 385.

[9] Billings, Little Parliament, 72.

[10] Haskell, 263-269. Tarter 26-30.

[11] Billings, Little Parliament, 71-72. Haskell, 262. Tarter 22-29. Thornton, 14-19.

[12] Billings, Little Parliament, 21-22; 89-91.

[13] McCartney, 206, 214, 335, 403.

[14] McCartney, 197-198. Tarter, 24-28.

[15] Billings, Little Parliament, 21-22. “Governors Before 1776 Who Did Not Finish Their Terms in Office.” Accessed online at Virginia Places. org. on 9/7/2021 at http://www.virginiaplaces.org/government/governorfinishs.html

[16] Haskell, 268-270; Tarter, 29-30.

I believe you are mistaken about Richard Stephens and John Harvey’s relationship. Harvey married Stephens’ widow, Elizabeth Peirsey Stephens, not his daughter. The widow was considerably younger than Stephens.

LikeLike

Thanks for catching that. I’ve made the correction, changing “daughter” to “widow.” Have a Happy New Year!

LikeLike