“Rich widows are the best commodity this country affords,” wrote Aphra Behn, an English author, in her play about Virginian society called The Widow Ranter, or the History of Bacon in Virginia. Written around 1680, Behn combined a romanticized version of Bacon’s Rebellion with the fictitious story of a woman who came to Virginia as a servant, married a rich merchant, and became an unconventional, tobacco-smoking widow who donned men’s clothes to rescue someone in one of Bacon’s battles. The Widow Ranter defied the accepted conventions of London ladies and even of her good friend, the married Madame Surelove, suggesting that widows wielded greater freedom and power in Virginia. The wealth that Virginia widows could bring to a subsequent marriage may not have been what many imagined, for they rarely had as fashionable clothes or lovely homes as rich English widows, but they could be the means to control and consolidate precious land. [1]

Early Deaths

Sarah Thorowgood was 31 years old with four young children when her husband Adam Thorowgood suddenly died. In their twelve years of marriage in Virginia, they acquired land, notoriety, and wealth. At the time of Adam’s death, he owned about 6,000 acres, had been a Burgess, and was serving as the Presiding Justice of the Lower Norfolk County Court as well as a member of the Governor’s Council. After becoming ill while at Jamestown, he fortunately had time to prepare a will before he died at age 36 in 1640, leaving Sarah a rich and notable widow in Virginia. See posts: “The Death of Adam Thorowgood ,”and “The Fascinating and Formidable Sarah Offley Thorowgood Gookin Yeardley”

Death was ever present in the life of 17th century Virginians. By 1640, the death rate had certainly declined since the disastrous early years of settlement. Yet, it was still much higher than in England or even New England due to disease and the conditions of the settlements. Morgan, in his study to approximate the life expectancy of those in Lower Norfolk County, estimated the average age of death at 47 years during the mid 1600s, whereas it was as long as 71 years for men in Andover, Massachusetts. Averages, though, do not tell the story of turmoil to families that resulted from shortened life expectancies, nor do they reveal unique characteristics of the Virginia population.[2]

Death was ever present in the life of 17th century Virginians. By 1640, the death rate had certainly declined since the disastrous early years of settlement. Yet, it was still much higher than in England or even New England due to disease and the conditions of the settlements. Morgan, in his study to approximate the life expectancy of those in Lower Norfolk County, estimated the average age of death at 47 years during the mid 1600s, whereas it was as long as 71 years for men in Andover, Massachusetts. Averages, though, do not tell the story of turmoil to families that resulted from shortened life expectancies, nor do they reveal unique characteristics of the Virginia population.[2]

Marriage and Remarriage in Virginia

While Puritans and Pilgrims mostly migrated to New England in established family groups, most immigrants to Virginia came singly as young adults contracted in indentureships. The first women arrived in Virginia in 1608 with the Second Supply of settlers, but their numbers were few until around 1619 when women started being recruited to come as servants and/or wives. About 80% of the women who came in the 17th century to Virginia were under an indentured contract. However, even with this increase in women’s immigration, the ratio of men to women in the colony only decreased from 6:1 to around 3:1. The formation of families was hindered not only by the imbalance in numbers, but by indentureship contracts which delayed marriage by prohibiting it during their time of service. Furthermore, while Virginia may have sounded like a single’s haven, the settlers had spread out on the land rather than clustering in towns, which did not foster occasions for social interaction.[3]

The kind and amount of power a woman had was largely determined by the English legal concept of coverture. A woman who was married had no legal standing as a feme covert apart from her husband. In general, any property or goods she had belonged to her husband who was in charge of all important decisions regarding their family. If a women was single (unmarried or widowed), she could, as a feme sole, own property, make contracts, and handle family decisions. In a few situations, married women were permitted to be a feme sole trader if she had a business or to act under a power of attorney if her husband was away. [4]

The kind and amount of power a woman had was largely determined by the English legal concept of coverture. A woman who was married had no legal standing as a feme covert apart from her husband. In general, any property or goods she had belonged to her husband who was in charge of all important decisions regarding their family. If a women was single (unmarried or widowed), she could, as a feme sole, own property, make contracts, and handle family decisions. In a few situations, married women were permitted to be a feme sole trader if she had a business or to act under a power of attorney if her husband was away. [4]

Although their overall numbers were less, women often outlived their husbands in Virginia, if they could survive childbirth. As many Virginian wives were relatively young when first widowed, a quick remarriage was common, and many experienced serial marriages, losing multiple spouses. A widow with land was a highly prized marriage “catch.” One of the powers Virginian widows exercised was control over their selection of their next marriage partner. Both men and women attempted to increase in social standing and wealth by marrying “up,” and a good match could increase the couple’s wealth and consolidate land into greater estates. Women who did not choose carefully, however, could find themselves in a worse situation if they reverted to a feme covert only to find that the new husband was irresponsible and treasure-seeking. Wise women began to use their widowed status as a feme sole to demand pre-nuptial agreements or to find ways to retain some control over what they had received from their prior marriage before tying the knot again. [5]

Although their overall numbers were less, women often outlived their husbands in Virginia, if they could survive childbirth. As many Virginian wives were relatively young when first widowed, a quick remarriage was common, and many experienced serial marriages, losing multiple spouses. A widow with land was a highly prized marriage “catch.” One of the powers Virginian widows exercised was control over their selection of their next marriage partner. Both men and women attempted to increase in social standing and wealth by marrying “up,” and a good match could increase the couple’s wealth and consolidate land into greater estates. Women who did not choose carefully, however, could find themselves in a worse situation if they reverted to a feme covert only to find that the new husband was irresponsible and treasure-seeking. Wise women began to use their widowed status as a feme sole to demand pre-nuptial agreements or to find ways to retain some control over what they had received from their prior marriage before tying the knot again. [5]

Sarah Thorowgood, relict, married John Gookin, her second husband, about a year after Adam’s death. He was the son of the prominent early immigrant Daniel Gookin, and became a Burgess and Justice for Lower Norfolk County. Sarah bore an additional child, Mary Gookin, shortly before John died suddenly in 1643, leaving her then with five young children and even more of an estate to manage. Her Gookin marriage seemed to be a good one that probably benefitted both–she providing him with greater wealth to manage, and he giving her stability and security. It appeared that she had loved him, as Sarah, at the time of her death, ordered them a black marble tombstone from England. One cannot determine if this was a slight to her other husbands, as we do not know the type of tombstones that had been provided for them because the graveyard and church sunk into the Lynnhaven River.

After Gookin’s death, Sarah waited four years as a feme sole before she married for the third time. She had the advantage of wealth and servants and an overseer to ensure her properties were maintained, livestock looked after, and tobacco cultivated as her cash crop. Sarah secured a pre-nuptial agreement to protect her family property prior to her prestigious marriage to Francis Yeardley, the son of a former governor. At the time of their wedding, Francis was 23 years old, 15 years younger than Sarah. It seemed to be a marriage of convenience and ambition for both which will be detailed in a future post. [6]

However, those widows whose husbands had been tenant farmers or were just starting out with property of their own could find themselves in serious straits if, at the time of death, it was time for planting or harvesting, and there was no one to help. As the tobacco economy frequently involved extended credit until a crop could be sold, widows might have had to settle their husband’s debts while fretting over an uncertain crop. There was also the care of small children to be considered by both young widows and widowers if they had to work in the fields. Thus, there were many pragmatic reasons for a quick remarriage and for women to willingly revert to their feme covert status. [7]

However, those widows whose husbands had been tenant farmers or were just starting out with property of their own could find themselves in serious straits if, at the time of death, it was time for planting or harvesting, and there was no one to help. As the tobacco economy frequently involved extended credit until a crop could be sold, widows might have had to settle their husband’s debts while fretting over an uncertain crop. There was also the care of small children to be considered by both young widows and widowers if they had to work in the fields. Thus, there were many pragmatic reasons for a quick remarriage and for women to willingly revert to their feme covert status. [7]

“Ghost” Families

These serial remarriages led to some complex family situations. If either spouse had children, it set up what have been called “ghost families,” where some vestige of the prior family grouping was maintained through protection of their inheritances in the blended families. In their study of 17th century Middlesex County, Virginia, the Rutmans traced a particularly convoluted situation: Mary and George Keeble married around 1640 and had seven children, three of whom were still alive when, as a widow, she remarried Robert Beverley in 1666. She had five more children before she died in 1678. Robert Beverley then remarried Katharine Hone, a widow with a child. After four more children with Katherine, Robert Beverley died in 1687, so this widowed widow immediately married Christopher Robinson, a widower with four more children. They then had four of their children prior to Katharine’s death in 1692. The chain of marriages and remarriages was finally broken with Christopher Robinson’s death the next year. “In sum, the progeny of six marriages among seven people amounted to twenty-five known children. Not one of these children could have grown to maturity without losing at least one parent and passing through a period under a stepparent.” [8]

While keeping track of inheritances could be a challenge, the emotional toll of deaths on both parents and siblings must have been great. In a study in Virginia, 73% of children had lost one parent and 30% had lost both their natural parents before they reached maturity. Even if the mother survived, children were legally considered orphans if the father had died, so the courts generally appointed guardians to oversee their care and estates. Parents had the heartbreak of not only losing spouses, but also children. In the Chesapeake area of 17th century Maryland, the death rate of infants was 25%, with 40-55% of children not reaching maturity. Deaths created a sense of impermanence in marriages and fluidity in the formation of familial ties. [9]

While keeping track of inheritances could be a challenge, the emotional toll of deaths on both parents and siblings must have been great. In a study in Virginia, 73% of children had lost one parent and 30% had lost both their natural parents before they reached maturity. Even if the mother survived, children were legally considered orphans if the father had died, so the courts generally appointed guardians to oversee their care and estates. Parents had the heartbreak of not only losing spouses, but also children. In the Chesapeake area of 17th century Maryland, the death rate of infants was 25%, with 40-55% of children not reaching maturity. Deaths created a sense of impermanence in marriages and fluidity in the formation of familial ties. [9]

Family and Community Supports

Another challenge was the lack of extended family support in Virginia. As so many immigrants came to the colony without family, there were rarely siblings, parents, or grandparents who could assist in difficult situations or offer condolences or advice in those early generations. With early deaths, many of those raised in Virginia entered adulthood without parental support. Despite distances between neighbors, Walsh found that women in the Chesapeake area developed supportive networks usually within a five-mile radius of their home which would have been a journey of an hour or two. Church attendance and court day gatherings also gave opportunities for women to develop friendships (or enemies). Here again, Sarah Thorowgood Gookin Yeardley was more fortunate than most in that her older sister, Ann, had immigrated to Lower Norfolk County with her second husband, Robert Hayes, and her children from both marriages, giving Sarah a family network in the colony. [10]

Another challenge was the lack of extended family support in Virginia. As so many immigrants came to the colony without family, there were rarely siblings, parents, or grandparents who could assist in difficult situations or offer condolences or advice in those early generations. With early deaths, many of those raised in Virginia entered adulthood without parental support. Despite distances between neighbors, Walsh found that women in the Chesapeake area developed supportive networks usually within a five-mile radius of their home which would have been a journey of an hour or two. Church attendance and court day gatherings also gave opportunities for women to develop friendships (or enemies). Here again, Sarah Thorowgood Gookin Yeardley was more fortunate than most in that her older sister, Ann, had immigrated to Lower Norfolk County with her second husband, Robert Hayes, and her children from both marriages, giving Sarah a family network in the colony. [10]

An example of community support being provided when family support failed was evidenced in the Lower Norfolk County Court record of May 23, 1655 concerning Henry Woodhouse, a planter, justice, vestryman, and Burgess of Lower Norfolk. Woodhouse, whose father had been a member of the London Company and Governor of Bermuda, purchased land in Lynnhaven near the Thorowgoods in 1642 when he arrived with his second wife Mary from England. The court noted: [11]

This court having heard many complaints concerning the unkind usage of Mrs. Woodhouse towards her husband Mr. Woodhouse in the time of his sickness, it is by this court thought fit that some adjacent neighbor by the appointment and consent of Mr. Woodhouse and the approbation of Col. Sibley shall have free liberty to resort to the house of Mr. Woodhouse to see that he have what shall be sufficient and necessary for him during his sickness and according to his quality.

This incident left many unanswered questions such as why Mrs. Woodhouse wasn’t performing her wifely duty, what was the unkind usage, and whether any neighborly assistance was ever given. Clearly his wife was not meeting community expectations, and there were concerned neighbors and friends who were willing to step in. Some have speculated that Mrs. Woodhouse had left him, but on that same day in court, a complaint from Mr. Woodhouse joined with a petition from Mrs. Woodhouse asking that their run-away servant receive 20 lashes. Mrs. Woodhouse was still at home and back in court in August when a maid servant of Mr. Woodhouse was put in the Sheriff’s protective custody (where she died) after “being most unchristianlike used by her mistress.” It is unknown whether Mr. Woodhouse ever fully recovered from his illness, as he died in November 1655. Whatever tensions may have existed in their marriage, he still left his wife in his will the customary third of his moveable estate and use of his plantation until his son was of age. [12]

This incident left many unanswered questions such as why Mrs. Woodhouse wasn’t performing her wifely duty, what was the unkind usage, and whether any neighborly assistance was ever given. Clearly his wife was not meeting community expectations, and there were concerned neighbors and friends who were willing to step in. Some have speculated that Mrs. Woodhouse had left him, but on that same day in court, a complaint from Mr. Woodhouse joined with a petition from Mrs. Woodhouse asking that their run-away servant receive 20 lashes. Mrs. Woodhouse was still at home and back in court in August when a maid servant of Mr. Woodhouse was put in the Sheriff’s protective custody (where she died) after “being most unchristianlike used by her mistress.” It is unknown whether Mr. Woodhouse ever fully recovered from his illness, as he died in November 1655. Whatever tensions may have existed in their marriage, he still left his wife in his will the customary third of his moveable estate and use of his plantation until his son was of age. [12]

Protecting Inheritances

Mrs. Woodhouse remarried Nathaniel Batts about six months after Henry died. Mr. Batts was a colorful individual who had worked with Francis Yeardley, Sarah’s third husband, in his exploration of North Carolina, making connections with its local Indian tribes. As Mr. Batts had some debts when they married in May 1656, Mary Woodhouse required a pre-nuptial agreement. Batts promised:

I…firmly bind and engage myself not to meddle with any of the said widow’s estate in what kind or nature soever to satisfy my debts …and further engage not to dispose of any of the above’s estate without her consent….

However, Mrs. Woodhouse Batts might have soon wished for her prior husband, for she had not chosen well. Being foresworn not to use his wife’s inheritance, he tried to use that of his stepchildren. In January 1656/7, only eight months after their marriage, Mary Batts was back in court with a petition because her husband “contrary to her expectation, destroys, spends, and consumes the estate left her children by her late husband.” No court action was recorded, but courts usually moved to preserve children’s inheritances. The situation of Mrs. Batts and her children, though, only got worse with apparently little financial support provided by her new husband. Two years later, she returned to court asking to sell two of the biggest steers which were in the children’s inheritances because her Woodhouse children “are in great want of clothes and other necessaries.” The court allowed them to be sold as long as they were replaced with two young steers. Despite the struggles under their stepfather, the Woodhouse children did finally receive their inheritances, marry well, and become prominent in the community. [13]

However, Mrs. Woodhouse Batts might have soon wished for her prior husband, for she had not chosen well. Being foresworn not to use his wife’s inheritance, he tried to use that of his stepchildren. In January 1656/7, only eight months after their marriage, Mary Batts was back in court with a petition because her husband “contrary to her expectation, destroys, spends, and consumes the estate left her children by her late husband.” No court action was recorded, but courts usually moved to preserve children’s inheritances. The situation of Mrs. Batts and her children, though, only got worse with apparently little financial support provided by her new husband. Two years later, she returned to court asking to sell two of the biggest steers which were in the children’s inheritances because her Woodhouse children “are in great want of clothes and other necessaries.” The court allowed them to be sold as long as they were replaced with two young steers. Despite the struggles under their stepfather, the Woodhouse children did finally receive their inheritances, marry well, and become prominent in the community. [13]

Power Over Property

While there were many complexities in being a Virginian widow, there was also power as a feme sole for those willing to grasp it. In 17th century Virginia, it was common for a husband to make his wife and mother of their young children the executrix of his will as she best knew their situation. This allowed her some control over when and how payments were made to claimants within the dictates of the will. Whereas England and New England had moved to restrict the customary widow’s 1/3 inheritance to just personal property, Virginia and Maryland allowed a more generous legacy in both personal and real property.

While there were many complexities in being a Virginian widow, there was also power as a feme sole for those willing to grasp it. In 17th century Virginia, it was common for a husband to make his wife and mother of their young children the executrix of his will as she best knew their situation. This allowed her some control over when and how payments were made to claimants within the dictates of the will. Whereas England and New England had moved to restrict the customary widow’s 1/3 inheritance to just personal property, Virginia and Maryland allowed a more generous legacy in both personal and real property.

However, increased control over property still did not mean equality between men and women. A widowed woman could own and manage land but not dispose of it, as she usually had only life time rights. At her death, the property would go to her husband’s heirs. If she remarried, her designated property would be controlled by the new husband unless other provisions, such as encumbrances, trusts, or prenuptial agreements had been put in place. The husband was supposed to have his wife’s consent, obtained during her private meeting with justices, before he could sell any of her dower property, but a wife dependent on her husband rarely voiced objections to her husband’s associates. Some dying husbands had provisions put in the will to rescind or limit what his widow would receive if she remarried. [14]

Whether sole or covert, women exerted economic control as consumers and mistresses of their households. This power was increased as a femme sole to include making larger purchases, entering into contracts, collecting debts, and engaging in business. As such, she was more frequently involved with the courts on a near equal basis with men in managing such business affairs, although she might have used an overseer or male relative to represent her. The complex interactions of women with the county courts will be discussed more in future posts. However, not all transactions were open to women. Land for a husband’s headrights was rewarded to widows posthumously, but I could not find a femme sole who herself arranged to receive land by bringing immigrants to Virginia. [15]

Forgotten Women

So many women who came to Virginia left little or no record of their lives. Not being able to connect Sarah Taylor with a husband or children, one can only wonder what brought her to the colony and when she became a widow. The inventory that was taken for the Lower Norfolk County Court at her death in November 1640 gives a more personal glimpse into a fashionable woman’s wardrobe than is usually found in inventories. It can be surmised she was then living in someone’s house as she had only her small “seabed” with pillows and bedding and 2 spoons as household items. Yet, Sarah Taylor had 5 smocks, wearing linen (undergarments?), 2 gowns with petticoats and waistcoats in addition to a silk gown with a “taffity” petticoat, shoes and stockings, 2 pairs of gloves, a hat, and a sea-green apron. Rarely is color mentioned in inventories, so it must have been impressive to the gentlemen who inventoried. She also had a looking glass (mirror) and comb and brush as well as thread and a smoothing iron. Maybe she had been a seamstress or a mantua (dress) maker, though all her items were recorded as old with nothing newly made. What dreams did she bring to Virginia along with those gowns? I hope she had occasion to wear her silk gown, taffity petticoat, and sea green apron in Virginia before she died. [16]

So many women who came to Virginia left little or no record of their lives. Not being able to connect Sarah Taylor with a husband or children, one can only wonder what brought her to the colony and when she became a widow. The inventory that was taken for the Lower Norfolk County Court at her death in November 1640 gives a more personal glimpse into a fashionable woman’s wardrobe than is usually found in inventories. It can be surmised she was then living in someone’s house as she had only her small “seabed” with pillows and bedding and 2 spoons as household items. Yet, Sarah Taylor had 5 smocks, wearing linen (undergarments?), 2 gowns with petticoats and waistcoats in addition to a silk gown with a “taffity” petticoat, shoes and stockings, 2 pairs of gloves, a hat, and a sea-green apron. Rarely is color mentioned in inventories, so it must have been impressive to the gentlemen who inventoried. She also had a looking glass (mirror) and comb and brush as well as thread and a smoothing iron. Maybe she had been a seamstress or a mantua (dress) maker, though all her items were recorded as old with nothing newly made. What dreams did she bring to Virginia along with those gowns? I hope she had occasion to wear her silk gown, taffity petticoat, and sea green apron in Virginia before she died. [16]

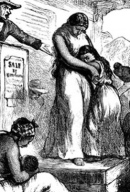

This discussion has obviously been about colonial white women. Tragically, enslaved Blacks lived in a permanent state of impermanency, never knowing when their families might be separated. Being considered among the “property” that created wealth, their marriages, if allowed, were not recognized, nor were their family ties respected. The death of a master created anxiety as to whether they would be sold or separated. They were denied the most basic of freedoms and powers. Their sorrows were unfathomable.[17]

This discussion has obviously been about colonial white women. Tragically, enslaved Blacks lived in a permanent state of impermanency, never knowing when their families might be separated. Being considered among the “property” that created wealth, their marriages, if allowed, were not recognized, nor were their family ties respected. The death of a master created anxiety as to whether they would be sold or separated. They were denied the most basic of freedoms and powers. Their sorrows were unfathomable.[17]

17th Century Space for Strong Women

Sarah Offley Thorowgood Gookin Yeardley died in 1657 at the age of 48. She buried three husbands, but raised 5 surviving children. She was strong and bold as a wife and widow in managing household affairs and estates. Sarah was relentless in pursing debts and defending her family’s reputation in the Lower Norfolk County Courts as a femme sole, yet repeatedly refused to give them the annual accounting of her children’s inheritances. Sarah contended that she should be exempt from the requirement to file in Orphan’s Court due to her status as the mother of the children and sole executrix and guardian “of all my children and their estates” according to Adam’s will. She even questioned the court’s jurisdiction in the matter. Sarah pushed the limits of woman’s power in her time. [18]

Because of the unique circumstances in 17th century Virginia, there was need for English women to assume greater responsibilities and to act with greater autonomy than elsewhere. However, as society became more stable, life expectancies extended, and the colony moved into the 18th century, a number of scholars have noted that the power and freedom given to women, especially widows, began to decrease. Sons, rather than wives, were made executors, women’s presence in the courts decreased, and widows’ opportunities to control property diminished. Linda Sturtz noted: “Seventeenth-century Virginia culture made space for self-willed women.” Sarah Thorowgood Gookin Yeardley was one of the brave women who filled that space. [19]

Because of the unique circumstances in 17th century Virginia, there was need for English women to assume greater responsibilities and to act with greater autonomy than elsewhere. However, as society became more stable, life expectancies extended, and the colony moved into the 18th century, a number of scholars have noted that the power and freedom given to women, especially widows, began to decrease. Sons, rather than wives, were made executors, women’s presence in the courts decreased, and widows’ opportunities to control property diminished. Linda Sturtz noted: “Seventeenth-century Virginia culture made space for self-willed women.” Sarah Thorowgood Gookin Yeardley was one of the brave women who filled that space. [19]

Footnotes:

- Morgan, Edmund S., American Slavery, American Freedom: The Ordeal of Colonial Virginia (New York: W.W. Norton & Co.,1975), 165. Snyder, Terri L., Rich Widows Are the Best Commodity This Country Affords: Gender Relations and the Rehabilitation of Patriarchy in Virginia 1660-1770, PhD Dissertation 1992. Copy located at Rockefeller Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. 1-2, 20-26.

- Morgan, 158-162.

- Horn, James, Adapting to a New World: English Society in the Seventeenth-Century Chesapeake (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press,1994), 204. Sturtz, Linda L., Within Her Power: Propertied Women in Colonial Virginia (New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2002), 5. Snyder, 54-57. Walsh, Lorena S., Women’s Networks in the Colonial Chesapeake, Presented to the Organization of American Historians, 198 . Copy located at Rockefeller Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1-2.

- Salmon, Marylynn, Women and the Law of Property in Early America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1986) 15-17, 55. Sturtz, 71-73.

- Morgan 160-165. Snyder, 55. Sturtz, 34-36.

- McCartney, Martha W., Jamestown People to 1800 (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company, 2012), 175-176, 403, 463. Paramore, Thomas C., Peter C. Stewart, and Tommy L. Bogger, Norfolk: The First Four Centuries (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1994), 37-38. Morgan, 167.

- Snyder, 123-126. Morgan 164.

- Sturtz, 13, 33-34. Rutman, Darrett B. and Anita H., “Now-Wives and Sons-in-Law; Parental Death in a Seventeenth-Century Virginia County” in The Chesapeake in the Seventeenth Century: Essays on Anglo-American Society, Thad W. Tate and David L. Ammerman, eds.(Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1979), 154-156.

- Rutman, 153. Morgan, 162, 168. Sturtz, 5. Billings, Warren, Thee Old Dominion in the Seventeenth Century (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2007), 380-381. Walsh, Lorena S., “Till Death Us Do Part: Marriage and Family in Seventeenth-Century Maryland,” in The Chesapeake in the Seventeenth Century: Essays on Anglo-American Society, Thad W. Tate and David L. Ammerman, eds.(Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1979), 143-147. Carr, Lois Green and Lorena S. Walsh, “The Planter’s Wife: The Experience of White Women in Seventeenth-Century Maryland” The William & Mary Quarterly, XXXIV: 344 (October, 1977), 542-543, 552.

- Horn, 216-218. Walsh, Networks, 2-7.

- Dorman, John Frederick, Adventurers of Purse and Person, Volume Three Families R-Z, 4th ed. (Baltimore:Genealogical Publishing Co., 2007), 678-679. Brayton, John A., Transcription of Lower Norfolk County, Virginia Records, Volume Two: Record Book “C” 1651-1656 (Baltimore: Clearfield Company, 2010), 338.

- Brayton, “C,” 337, 354.

- Brayton, “C,” 477. Dorman, 680. Brayton, John A., Transcription of Lower Norfolk County, Virginia Records, Volume One: Wills and Deeds, Book D 1656-1666 (Jackson, Mississippi: Cain Lithographers, Inc., 2007), 45, 218.

- Morgan, 165-166. Snyder, 144-150. Salmon, 18-21, 151-152.

- Sturtz, 5-7. Snyder, 200-208.

- Walter, Alice Granbery, Lower Norfolk County, Virginia, Court Records : Book “A,” 1637-1646 (Baltimore: Clearfield, 2009), 42.

- Morgan, 316-317. Sturtz, 52-54.

- Morgan 170. Walter, Alice Granbery, Lower Norfolk County, Virginia, Court Records : Book “B,” 1646-1651/2 (Baltimore: Clearfield, 2009), 47-48.

- Snyder, 128. Sturtz, 10, 41.

Fascinating exploration about the power of a widow in this era! Well done as usual!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: John Gookin, Sarah Thorowgood, Nansemond Indians, and Virginia Puritans from Ireland – Thorowgood World

Pingback: Lady Temperance and Preserving the Disputed Inheritance of Governor Yeardley’s Children in 17th Century Virginia – Thorowgood World

Pingback: Interwoven Yeardley, Custis, and Thorowgood Lives Part II: Marriage, Death, Taverns, Conspiracy, and an Expensive Face in 17th Century Virginia – Thorowgood World