The deposition of Henry Catelin…with Robert Hayes being appointed by order of the Court…to (ap)praise and divide the estate of Capt. Adam Thorowgood deceased doth say upon his oath that Mr. John Gookin and his wife Sarah were very careful to have the estate equally divided for the children[1]

Captain John Gookin, though not as well known or remembered as his famous father Daniel Gookin, Sr., or brother Daniel Gookin, Jr., left his mark on early life in Virginia through his complex, if short, life. John was respected and trusted by his community and competent in the handling of his estates and business affairs. At the early and unexpected death of her first husband, Sarah Thorowgood had become a wealthy widow in Lower Norfolk County, Virginia, responsible for a large estate and four children under 10 years of age. Within a year, she chose to marry John Gookin. See post “The Widow Thorowgood.”

English With An Irish Plantation

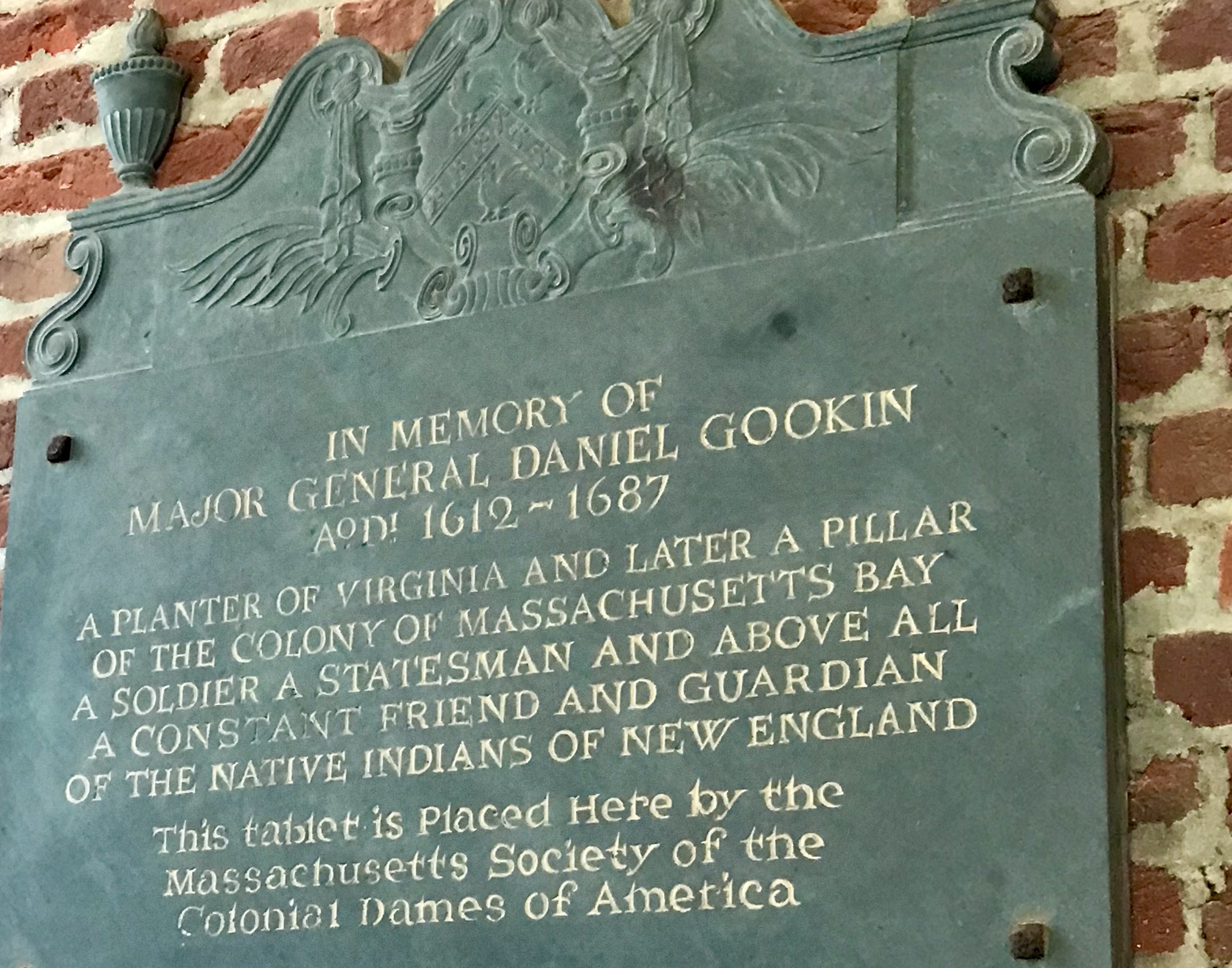

The Gookins were an established family in Kent, England in the 16th and 17th century with an acquired family seat at Ripple Court. On January 31, 1608/9, Daniel Sr. married Mary Byrd, the daughter of the learned Rev. Richard Byrd, a canon of Canterbury Cathedral. Daniel Sr. and Mary had five sons, naming their third Daniel (Jr.) and their fourth John (the name of Daniel Sr.’s father and brother). Daniel Jr. was born in 1612, and, based on the birthdates of the other brothers, John, the son of Daniel Sr., would have been born about 1613. Although Daniel Sr. received English lands from his father, he decided around 1611 to move his family to join his older brother Vincent Gookin who had established himself in Munster, Ireland, in 1606. John, the father of Daniel Sr. and Vincent, joined them soon thereafter.[2]

The Munster region in southwest Ireland was still recovering from the devastation of the Desmond Rebellions and the Nine Year’s War (Tyrone’s Rebellion) between the English and the Irish which did not conclude until 1603. The English poet Edmund Spenser, who fought in those wars, said that in parts of Munster, “they were brought to wretchedness…creeping forth upon their hands, for their legs could not bear them; they looked Anatomies of death; they spoke like ghosts crying out from their graves….a most populous and plentiful country suddenly left void of man or beast.” Shortly thereafter, the Gookins joined other “New English” Protestant settlers who were granted land to establish plantations on the confiscated lands of the Irish rebels. It was here that Daniel Jr. and John Gookin probably spent most of their childhoods.[3]

Vincent had settled at Courtmacsherry in County Cork to take up the profitable pilchard fishing industry. Daniel Sr. took residence in Coolmain across the bay from Vincent before purchasing the castle and lands of Carrigaline in 1616. Daniel Sr., though, had his sights on more than a piece of Ireland. For some, colonization in Ireland was a step towards the greater adventure of settling in the New World. Daniel Sr. was likely inspired and encouraged by his neighbor Captain William Neuce who was his business partner, a veteran of the Nine Years War, and founder of the successful Irish towns of Bandon-Bridge and Newcestown. Neuce and Gookin both invested in the Virginia Company, applied for land patents, and made plans to go to Virginia.[4]

Ventures to Virginia

When Capt. Neuce proposed to bring 1,000 settlers to Virginia at his own expense by 1625, the Virginia Company of London received the offer with enthusiasm and awarded him not only a patent, but privileges and the title of Marshall of the Colony, although they acknowledged “no present necessity ” for such an office. William, his wife, and brother Thomas came to Virginia in 1620 and settled in Elizabeth City (today’s Hampton/Newport News). Thomas became deputy for distribution of the Company lands, built two reception houses for new immigrants, and fortified his home to shelter neighbors.

Likely inspired by them, Daniel Gookin Sr. had an approved proposal to bring cattle out of Ireland to Virginia by November 1620, and in July 1621, he asked the Council to be granted a plantation as large as was given to William Neuce. Daniel Gookin Sr. arrived in Virginia from Ireland in November 1621 on the Flying Harte to the acclaim of the Virginia Council:[5]

Likely inspired by them, Daniel Gookin Sr. had an approved proposal to bring cattle out of Ireland to Virginia by November 1620, and in July 1621, he asked the Council to be granted a plantation as large as was given to William Neuce. Daniel Gookin Sr. arrived in Virginia from Ireland in November 1621 on the Flying Harte to the acclaim of the Virginia Council:[5]

There arrived here about the 22nd of November a ship of Mr. Gookins out of Ireland wholly upon his own adventure …which was so well furnished with all sorts of provision, as well with cattle as we could wish all follow their example, he hath also brought with him about 50 more…that adventure besides some 30 other Passengers. We have according to their desire seated them at Newports News, and we do conceive great hope (if the Irish plantation prosper) that from Ireland great multitudes of people will be like to come hither.

Despite glorious beginnings, fate was not kind to these ambitious and well-intentioned neighbors from Ireland. Thomas Neuce died of illness in 1622. Captain William Neuce was appointed to the Council by Governor Yeardley and recommended for knighthood, but was dead by January 1623. Daniel Sr. continued his efforts in colonization, but never attained financial success for his endeavors and died impoverished in Ireland in 1633. [6]

The same fall that Gookin Sr. arrived in Virginia, the 17-year-old Adam Thorowgood disembarked from the Charles at Jamestown and proceeded to Water’s Creek near Blount Point in Elizabeth City to serve as an indentured servant to Edward Waters. Daniel Gookin Sr. claimed the land just below Water’s Creek on the James River and called his new home Marie’s Mount. Being neighbors, their paths surely crossed, but with no thought that their families would eventually intertwine. They were both survivors of the Powhatan Uprising of 1622, only months after their arrival. [7] See post “1622: The Powhatan Uprising”

Marie’s Mount

Good real estate often stays good real estate. The site that Daniel Gookin Sr. chose on the James River not far from the confluence with the Nansemond River is today covered by the Newport News shipyard (America’s largest industrial shipbuilder) and a terminus for the largest coal exporting site in the U.S. While nothing of Marie’s Mount remains to be found, a small window opened between 1928 and 1935 when a Newport News physician, Jerome Knowles, found a large exposed 17th century trash pit on the eroding banks of the James River in the area of Marie’s Mount. Dr. Knowles eventually donated the artifacts to Iver Noel Hume, the director of archaeology for Colonial Williamsburg, where the collection still resides. Dr. Hume noted the artifacts were from the 2nd quarter of the 17th century (the Gookin era) and stated there was “the finest group of Pisa marbled slipwares that I have seen or heard of from any other site.” The quantity and type of artifacts in this happenstance collection seemed to be in line with the presence of around 30-50 people at the Gookin site. [8]

Good real estate often stays good real estate. The site that Daniel Gookin Sr. chose on the James River not far from the confluence with the Nansemond River is today covered by the Newport News shipyard (America’s largest industrial shipbuilder) and a terminus for the largest coal exporting site in the U.S. While nothing of Marie’s Mount remains to be found, a small window opened between 1928 and 1935 when a Newport News physician, Jerome Knowles, found a large exposed 17th century trash pit on the eroding banks of the James River in the area of Marie’s Mount. Dr. Knowles eventually donated the artifacts to Iver Noel Hume, the director of archaeology for Colonial Williamsburg, where the collection still resides. Dr. Hume noted the artifacts were from the 2nd quarter of the 17th century (the Gookin era) and stated there was “the finest group of Pisa marbled slipwares that I have seen or heard of from any other site.” The quantity and type of artifacts in this happenstance collection seemed to be in line with the presence of around 30-50 people at the Gookin site. [8]

Daniel Sr. did not bring his family with him to Virginia in 1621, but in the few months before the unforeseen Powhatan uprising, he apparently had sufficient houses and fortifications constructed for the 35 or so people at Marie’s Mount so that there was not the devastation that occurred at other settlements. Feeling confident, he did not obey the Commissioner’s command to pull his group back to Elizabeth City for safety, but continued to cultivate his land. A few months later, Daniel Sr. returned to London, then Ireland, leaving his plantation in the care of his servants. He sent additional supplies and 40 more settlers, but never himself returned to Virginia.

Despite the provisions and protective buildings, the plantation suffered from disease and continued attacks from the Nansemond warriors. An inventory for the 1624 Muster revealed that Marie’s Mount had only 20 settlers remaining, but was well provisioned with, among other items, 16 “pieces” (guns), 200 lbs. of shot, 20 swords, 2,000 dried fish, and 15 cattle. Back in England, Daniel Sr. was appointed by the Virginia Company to assess colonists’ losses from the massacre. [9]

Not giving up hope despite the risks, Daniel Sr. sent his two sons, Daniel Jr. and John, to the plantation at Marie’s Mount. In 1630 Daniel “Gooking, gent. in Newport Newes, Virginia,” who would have turned 18 , granted land to the servant Thomas Addison for his service to the family. There were also reports that Daniel Jr. was involved in trade and exploration among the Indians in the upper Potomac region and developed skills as an interpreter of the Algonkian language. In 1633, Captain David DeVries, a Dutch merchant, visited the “wealthy planter named Goegen” when anchored off Newport News. When Daniel Gookin Sr. died in 1633, he left Marie’s Mount jointly to Daniel Jr. and John, implying that John had been living there as well. Later, they conveyed the land to John Chandler.[10]

Living Along the Nansemond River

As the threats of Indian attacks decreased and settlers started moving south of the James River, New Norfolk County was created in 1636. Just a year later, that county was ready to be divided again, becoming Upper Norfolk County (which became Nansemond, then Suffolk County) and Lower Norfolk County. Over 35,000 acres were claimed in patents in just three years. Adam Thorowgood received a 5,000+ acre grant in Lower Norfolk County (later Princess Ann County).

The Gookin brothers each acquired land in Upper Norfolk. Daniel claimed the upper knob of land between Chuckatuck Creek and the western bank of the Nansemond River near where it joins the James River. In October 1636, John received 500 acres a little south of Daniel’s plot but also along the upper western bank of the Nansemond. See post “English Settlers to Virginia Beach”

John ultimately acquired 1490 acres, including 640 acres in Lower Norfolk County adjoining the Thorowgood estate in October 1641 after his marriage to Sarah Thorowgood. This land came to him for transporting 13 persons, which included 7 unnamed negroes. John and Daniel Gookin also patented land on the Rappahannock River along with Richard Bennett and other neighbors from the Nansemond region, although neither were resident there. [11]

John ultimately acquired 1490 acres, including 640 acres in Lower Norfolk County adjoining the Thorowgood estate in October 1641 after his marriage to Sarah Thorowgood. This land came to him for transporting 13 persons, which included 7 unnamed negroes. John and Daniel Gookin also patented land on the Rappahannock River along with Richard Bennett and other neighbors from the Nansemond region, although neither were resident there. [11]

Early settlers constructed Nansemond Fort probably as a defensive palisade when they started to move into this isolated area. The fort site was occupied by English settlers continuously from 1635-1680, but evolved in its uses and construction. Fortunately, an archaeological excavation was conducted at the site under Nicholas Luccketti of the James River Institute for Archaeology in 1988 prior to the land being developed. It appeared to be a private fortification that served for both protection and to separate ownership and work areas. Dr. Luke Pecocaro noted similarities between the construction at the fort during the 1640s and Irish bawn enclosures and fortifications. Settlers, such as the Gookins and others with Irish plantations, seemed to draw upon their Irish experiences in establishing their Virginia homesteads.[12]

Puritan by Association

Daniel Gookin Jr. was a well known Puritan in Virginia, Maryland, and Massachusetts. But was John? There were those fervent Puritan devotees who left England for New England in that era, but there were many in England and even Virginia with more moderate Puritan leanings who desired church reform and simplification, supported Puritan Parliament initiatives, and were concerned with King Charles I and his brother James II’s toleration of Catholic “popery.” Religious affiliation in Virginia was somewhat obscured by the limited number of ministers available for congregations.[13]

While most government officials and Jamestown residents remained staunchly Anglican and tried to enforce adherence to the official religion, there were dissensions in Virginia as well as England in this pre-English Civil War era. The Munster area in Ireland that the Gookins came from was also known to have Puritan connections. Puritan influence in Virginia became particularly strong in Upper and Lower Norfolk and on the Eastern Shore. Richard Bennett, a friend and neighbor of the Gookins, went on to become the first Governor under the Puritan Commonwealth Era government.[14]

While most government officials and Jamestown residents remained staunchly Anglican and tried to enforce adherence to the official religion, there were dissensions in Virginia as well as England in this pre-English Civil War era. The Munster area in Ireland that the Gookins came from was also known to have Puritan connections. Puritan influence in Virginia became particularly strong in Upper and Lower Norfolk and on the Eastern Shore. Richard Bennett, a friend and neighbor of the Gookins, went on to become the first Governor under the Puritan Commonwealth Era government.[14]

Lacking a qualified minister, Daniel Gookin, Richard Bennett, and 69 other citizens from Upper Norfolk signed a letter in May 1642 addressed, not to William Laud, the Archbishop of Canterbury, but to Puritan “Pastors and Elders of Christ Church in New England.” They requested ministers be sent them from New England “that the word of God might be planted amongst us by Faithful Pastors and Teachers.” Unfortunately, only 10 of the 71 signers are now known. John Gookin was at that time living in Lower Norfolk, but still had land in Upper Norfolk, so may well have been one of the signatories. As early as 1633 when the Dutch visitor, Capt. DeVries, discussed English politics with Daniel Jr., Daniel leaned toward supporting Parliament, rather than the royalists. Daniel Jr. also became involved in intercolonial trade with the Puritans in New England even before he moved there. [15]

Lacking a qualified minister, Daniel Gookin, Richard Bennett, and 69 other citizens from Upper Norfolk signed a letter in May 1642 addressed, not to William Laud, the Archbishop of Canterbury, but to Puritan “Pastors and Elders of Christ Church in New England.” They requested ministers be sent them from New England “that the word of God might be planted amongst us by Faithful Pastors and Teachers.” Unfortunately, only 10 of the 71 signers are now known. John Gookin was at that time living in Lower Norfolk, but still had land in Upper Norfolk, so may well have been one of the signatories. As early as 1633 when the Dutch visitor, Capt. DeVries, discussed English politics with Daniel Jr., Daniel leaned toward supporting Parliament, rather than the royalists. Daniel Jr. also became involved in intercolonial trade with the Puritans in New England even before he moved there. [15]

Adam Thorowgood was another with Puritan leanings. His brother, Rev. Thomas Thorowgood, in England became one of the Puritan Westminster Divines. Sarah and Adam were married in a congregation in London with strong Puritan ties, so she would not have opposed Puritan views in her new husband. In the 1640s, many in Lower Norfolk County supported their popular Puritan preacher, Rev. Thomas Harrison, even though he was brought to court for not teaching out of the Anglican Common Book of Prayer and was ultimately forced to leave by Berkeley’s government. I would put John Gookin at least in the probably Puritan leaning category. The next post will further explore Puritan connections with Virginia , including Daniel Gookin Jr.’s contributions to the Puritan cause in New England. [16]

Mr. and Mrs. John Gookin

How and when Sarah Thorowgood met John Gookin is unknown. Adam would have known John’s father from Marie’s Mount. Being influential and wealthy families in the New Norfolk area, the Thorowgoods and Gookins would have interacted. John was about 28 years old and never married when the 31-year-old widow Sarah Thorowgood agreed to marry him out of many possible suitors. They were married before March 15, 1640/41 when the courts ordered Mrs. Sarah Gookin to make an inventory of Adam Thorowgood’s estate. Over the next year, Sarah and John had a child, Mary Gookin. Mary grew up to marry Capt. William Moseley II, the son of William I and Susannah Moseley, the very couple who exchanged jewels for cattle with Sarah and her third husband, Francis Yeardley, when they arrived from Rotterdam.[17]

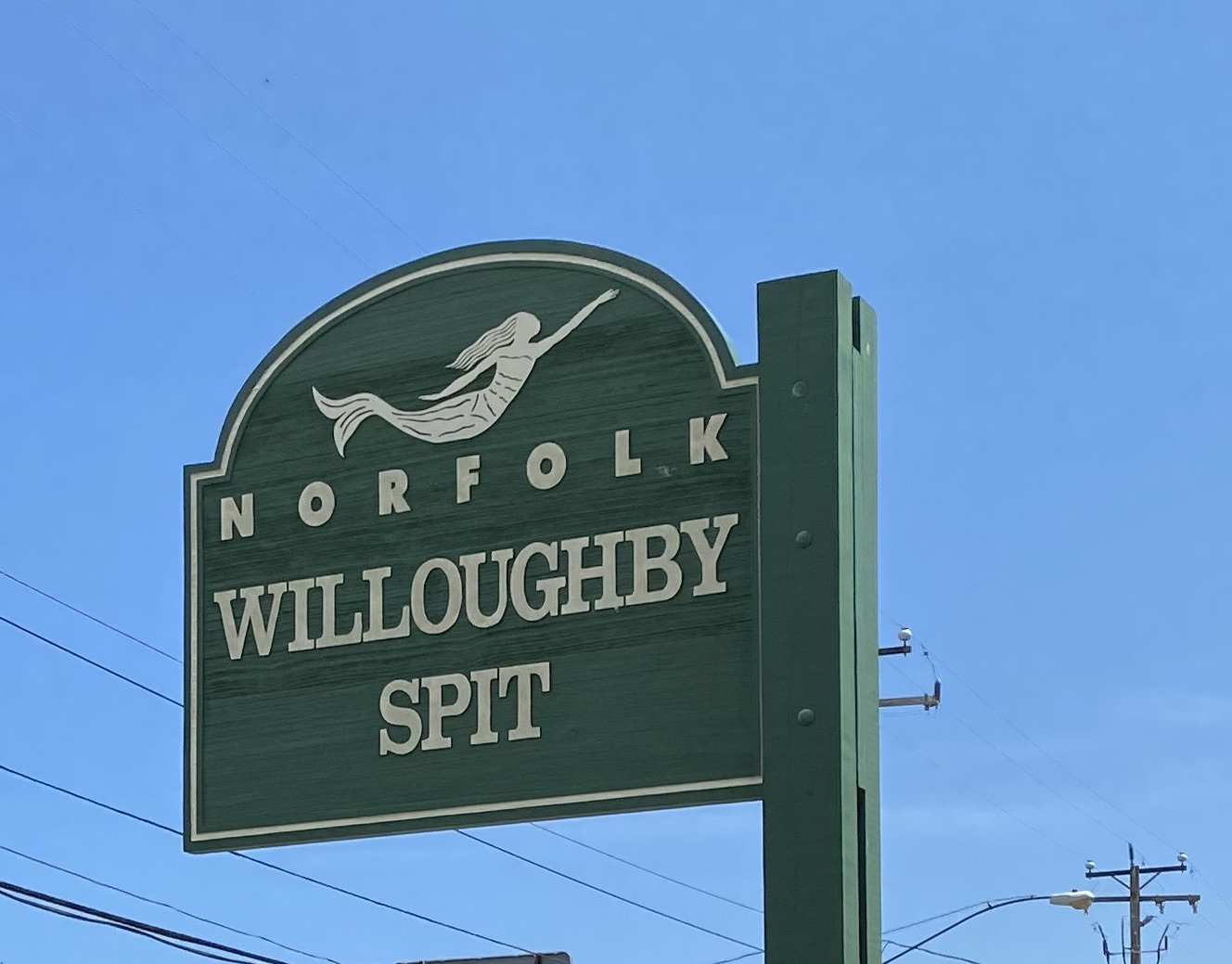

As would be expected under the legal concept of coverture, John Gookin took financial responsibility for the Thorowgood estate after the marriage. He pursued debt collection and represented the Thorowgood heirs in land matters in court. After his marriage, John stepped out of his older brother’s shadow and was quickly elevated to responsible positions and accorded increased status. Thomas Willoughby and John Gookin agreed to jointly build a store at Willoughby Point for the benefit of the community. John later was designated to provide a ferry at Lynnhaven on the lands of the Thorowgood heirs. “John Gookin’s Landing,” referred to in later deeds, was on Samuel Bennett’s Creek near the site called Ferry where the Old Donation Church was built. John was reported to represent Lower Norfolk County in the Assembly in 1640. [18]

As would be expected under the legal concept of coverture, John Gookin took financial responsibility for the Thorowgood estate after the marriage. He pursued debt collection and represented the Thorowgood heirs in land matters in court. After his marriage, John stepped out of his older brother’s shadow and was quickly elevated to responsible positions and accorded increased status. Thomas Willoughby and John Gookin agreed to jointly build a store at Willoughby Point for the benefit of the community. John later was designated to provide a ferry at Lynnhaven on the lands of the Thorowgood heirs. “John Gookin’s Landing,” referred to in later deeds, was on Samuel Bennett’s Creek near the site called Ferry where the Old Donation Church was built. John was reported to represent Lower Norfolk County in the Assembly in 1640. [18]

John Gookin, Esq., Commissioner and Commander

In 1642, Governor Berkeley appointed John Gookin, Esq., a commissioner of the Lower Norfolk County Court and Commander of all the Western Shore of Linhaven. That same year, his brother Capt. Daniel Gookin Jr. was also appointed by Gov. Berkeley as a commander in Upper Norfolk. John assumed responsibilities previously held by Adam Thorowgood and became the presiding justice of the court that year. The elegant and spacious Thorowgood home into which John had moved was once again in the rotation of places to hold court. However, being a justice did not prevent him from being sued. John Gookin was held financially liable for the physical injuries that his overseer, who had then died, had inflicted on another servant.[19] See post “Archaeological Discovery of …Chesopean Home.”

The first jury trial in Lower Norfolk County also concerned John Gookin. Whereas fellow justices generally had no qualms about passing judgment on cases involving their peers, they decided that using a jury of 12 men provided the “most equitable way” in this matter. As noted in a prior post, the hogs belonging to Capt. John Gookin escaped their pen and damaged the corn field of his neighbor Richard Foster. As Gookin had installed sturdy fencing to try to keep his hogs in and Foster had none to keep animals out, the jury found for Gookin. At that time, planters were expected to fence in their plants if they wanted to protect them from roaming animals. [20]

The first jury trial in Lower Norfolk County also concerned John Gookin. Whereas fellow justices generally had no qualms about passing judgment on cases involving their peers, they decided that using a jury of 12 men provided the “most equitable way” in this matter. As noted in a prior post, the hogs belonging to Capt. John Gookin escaped their pen and damaged the corn field of his neighbor Richard Foster. As Gookin had installed sturdy fencing to try to keep his hogs in and Foster had none to keep animals out, the jury found for Gookin. At that time, planters were expected to fence in their plants if they wanted to protect them from roaming animals. [20]

The Gookins and the Nansemond Indians

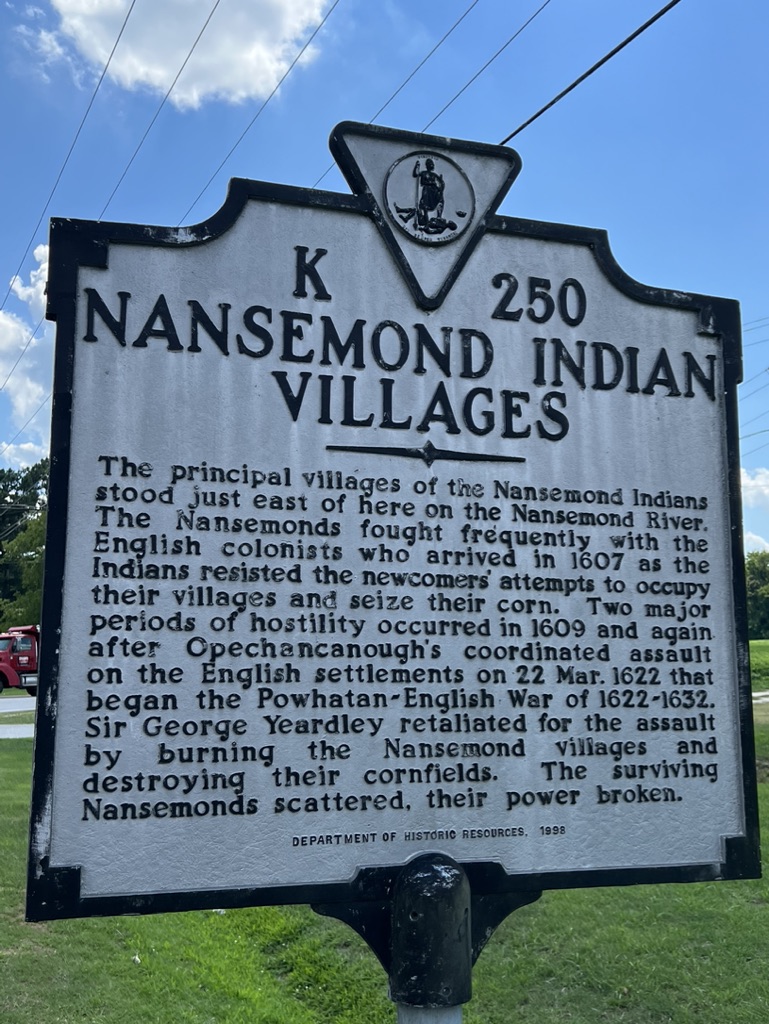

In the early years of the Jamestown Settlement, settlers had the expectation that the Indians would provide them corn, either by trade or force. The Nansemond tribe south of the James River under the paramount chiefdom of Powhatan first encountered Capt. John Smith and the English in 1608 when, under threat, they provided 400 baskets of corn. Although in the English perspective they parted good friends, hostilities increased as more demands were made for food and land. In 1609, Capt. John Martin was ordered to settle with his soldiers on Nansemond lands, but two of his advance soldiers went missing and were later found dead. After having been told that his men had been sacrificed and that “their brains had been cut and scraped out of their heads with mussel shells,” Capt. Martin ordered a complete destruction and desecration of the Nansemond’s sacred Dumpling Island. George Percy reported: [21]

In the early years of the Jamestown Settlement, settlers had the expectation that the Indians would provide them corn, either by trade or force. The Nansemond tribe south of the James River under the paramount chiefdom of Powhatan first encountered Capt. John Smith and the English in 1608 when, under threat, they provided 400 baskets of corn. Although in the English perspective they parted good friends, hostilities increased as more demands were made for food and land. In 1609, Capt. John Martin was ordered to settle with his soldiers on Nansemond lands, but two of his advance soldiers went missing and were later found dead. After having been told that his men had been sacrificed and that “their brains had been cut and scraped out of their heads with mussel shells,” Capt. Martin ordered a complete destruction and desecration of the Nansemond’s sacred Dumpling Island. George Percy reported: [21]

We beat the savages out of the island, burned their houses, ransacked their temples, took down the corpse’ of their dead kings from off their tombs, and carried away their pearls, copper, and bracelets where with they do decore their kings’ funerals.

Thereafter, the English and Nansemonds were avowed enemies. The Nansemonds participated in the Powhatan uprising of 1622 and attacked Daniel Gookin Sr.’s Marie’s Mount and Edward Water’s Blount Point where they kidnapped Adam Thorowgood’s master and mistress. However, Edward Bennett’s plantation bore the brunt of that Nansemond attack with 53 dead. As noted earlier, the Nansemonds continued to periodically attack settlers at Marie’s Mount. The English sought revenge, but it was not until the late 1630s that the Nansemond threat was lessened, and they started to withdraw upriver or into the southern and northwestern branches of the Nansemond River.[22]

Thereafter, the English and Nansemonds were avowed enemies. The Nansemonds participated in the Powhatan uprising of 1622 and attacked Daniel Gookin Sr.’s Marie’s Mount and Edward Water’s Blount Point where they kidnapped Adam Thorowgood’s master and mistress. However, Edward Bennett’s plantation bore the brunt of that Nansemond attack with 53 dead. As noted earlier, the Nansemonds continued to periodically attack settlers at Marie’s Mount. The English sought revenge, but it was not until the late 1630s that the Nansemond threat was lessened, and they started to withdraw upriver or into the southern and northwestern branches of the Nansemond River.[22]

With many of the Powhatan tribes subdued and pushed off their lands, the Virginia General Assembly took a more reasoned approach in 1640 in handling individual conflicts between Indians and the English. A law was passed that if an Englishman had a grievance against an Indian, he “should take it to the nearest militia commander, who would then detain without violence the next available Indian person from the same tribe as the one accused,” who would then be exchanged for the culprit. It was under this law, then, that Commander John Gookin reported to the colony’s Quarter Court at James City in November 1642 the “outrages and robberies committed by the Indians belonging to Nansemond in the County of Upper Norfolk and secured an order that they should be punished.” The Nansemond crimes must have occurred in Lower Norfolk, but as the Nansemonds lived in Upper Norfolk, it fell to John’s brother, Commander Daniel Gookin, “to approach the Nansemond chief, for return of the stolen items and to apprehend the culprits.” The outcome is unknown. [23]

However, not all relations with the Nansemonds were hostile. In 1638, John, the son of Captain Nathaniel Bass, married a Christianized Nansemond woman, ” ye daughter of ye King of ye Nansemond Nation, by name Elizabeth.” Other Nansemonds also converted and married into the Bass family, resulting in a group of Christianized Nansemonds during the 17th and 18th centuries that were allowed to continue to live on their lands. Some of their descendants are still living in Portsmouth and Suffolk County, Virginia. [24]

An Early Death

John Gookin was dead by November 22, 1643 at the age of 30. Sarah Offley Thorowgood Gookin, 33, was once again a widow, now with 5 young children and responsibility for administering John’s estate as well as that of her former husband Adam Thorowgood. No record exists with Sarah’s thoughts about her husbands or her feelings of loss with their deaths. Nor do we know the cause of John’s death or the arrangements she made for his burial. However, he must have held a special place in her heart. At the time of her death 14 years later, she ordered two black marble tombstones from England, one being inscribed:

John Gookin was dead by November 22, 1643 at the age of 30. Sarah Offley Thorowgood Gookin, 33, was once again a widow, now with 5 young children and responsibility for administering John’s estate as well as that of her former husband Adam Thorowgood. No record exists with Sarah’s thoughts about her husbands or her feelings of loss with their deaths. Nor do we know the cause of John’s death or the arrangements she made for his burial. However, he must have held a special place in her heart. At the time of her death 14 years later, she ordered two black marble tombstones from England, one being inscribed:

Here lyeth ye body of

Captain John Gookin

and also ye body of

Mrs. Sarah Yeardley

who was wife to Captain Adam Thorowgood

first, Captain John Gookin and

Colonel Francis Yeardley

who deceased August 1657

This inscription was recorded in 1819 when someone visited the graveyard of the first Lynnhaven Church that was sinking into the Lynnhaven River. Today there is only a memorial near the site of church and graveyard. There was no record made of what had been written on the second black marble tombstone or any of the other graves at the site. However, by 1853, all vestiges of the church and graveyard were gone. It was reported that “a tall man may wade out to this submerged burial-place and feel with his feet… the gravestones and their inscriptions.” William Forrest in his description of the Lynnhaven at that time further reflected, [25]

the remains of those who were interred there, now lie low beneath the sandy band of the river; and over the stones which mark ‘a couch of lowly sleep,’ rolls on the cool, clear flood of Lynnhaven….How deeply, how strangely, how securely buried!

Special thanks to Dr. Luke Pecoraro, Director of Archaeology, Drayton Hall, South Carolina, for his insights and assistance.

Footnotes

[1] Walter, Alice Granberry, Lower Norfolk County, Virginia Court Records Book “A” 1637-1646 (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company, 1994), 100.

[2] Gookin, Frederick William, Daniel Gookin, 1612-1687, Assistant and Major General of the Massachusetts Bay Colony (Chicago: privately printed, 1912; Reprinted through Bibliolife), 11-16, 30.

[3] Pecoraro, Luke J. “Mr. Gookin Out of Ireland, Wholly Upon His Owne Adventure”: An Archaeological Study of Intercolonial and Transatlantic Connections in the Seventeenth Century, PhD. Dissertation, Boston University Theses and Dissertations, 2015, 85-93. Gookin, 29-30. “Desmond Rebellions,” Wikipedia, accessed online August 1, 2022.

[4] Pecoraro, 92-95, 100. Kingsbury, Susan Myra, The Records of the Virginia Company of London volume IV (Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1935), 210.

[5] Gookin, 38-39. Kingsbury, Susan Myra, The Records of the Virginia Company of London volume III (Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1933), 587. McCartney, Martha W., Virginia Immigrants and Adventurers 1607-1635: A Biographical Dictionary, (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company, 2007), 519.

[6] Gookin, 50-55. Horning, Audrey, Ireland in the Virginian Sea: Colonialism in the British Atlantic (Chapel Hill: North Carolina University Press, 2013), 315-316. McCartney, 519-520. Percoraro, 39.

[7] Pecoraro, 11-12. Stauffer, W.T., “The Old Farms,” William and Mary College Quarterly Historical Magazine, 14:3 2nd series (July 1934), 203-204.

[8] Pecoraro, 263-264.

[9] Pecoraro, 40-42. McCartney, 332.

[10] Pecoraro, 44-48. Stauffer, 203-204.

[11] Gookin, 57. Nugent, Nell Marion, Cavaliers and Pioneers: Abstracts of Land Patents and Grants 1623-1666 (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., Inc., 1979) 100, 129. Mason, G.C. “The Colonial Churches of Nansemond County, Virginia,” William and Mary College Quarterly Historical Magazine, 21:1 series 2 (January 1941), 37-38. Pecoraro, 184.

[12] Horning, 342. Pecoraro, 211-214, 241.

[13] Gookin, 65. Butterfield, Kevin, “Puritans and Religious Strife in the Early Chesapeake,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, 109:1 (January 2001), 6-8.

[14] Pecoraro, 44, 50-52. Butterfield, 9-11. Hatfield, April Lee, Atlantic Virginia: Intercolonial Relation in the Seventeenth Century (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004), 115-116.

[15] Butterfield, 11-13. Hatfield, 105-106, 116. Pecoraro, 44, 50-52. Neill, Edward D., Virginia Carolorum: The Colony Under the Rule of Charles the First and Second (Albany:Joel Munsell’s and Sons, 1886, reprinted by Scholar Select), 167-168.

[16] Butterfield 10-11, 22-28.

[17] Walter, 45. Dorman, John Frederick, Adventurers of Purse and Person 1607-1624/5 volume 2 (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., Inc., 2005, fourth edition), 99-105, 107.

[18] Walter, 66, 89, 113, 116b, 118. McCartney, Martha W., Jamestown People to 1800 (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company, 2012), 175-176. Kellam, Sadie Scott and V. Hope Kellam, Old Houses in Princess Anne Virginia (Portsmouth, VA: Printcraft Press, 1931), 27-28.

[19] Walter, 90, 95, 97, 100. Gookin, 65. Pecoraro, 49.

[20] Walter, 103.

[21] Rountree, Helen C., Pocahontas’s People: The Powhatan Indians of Virginia through Four Centuries (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1990), 47, 52. Percy, George, “A True Relation of the Proceedings and Occurrents of Moment which Have Happened in Virginia” in Edward Wright Haile (ed.) Jamestown Narratives (Champlain, Virginia: Roundhouse, 1998), 501.

[22] Rountree, 79-82.

[23] Rountree, 83-84. Dorman, 103. Horning, 342.

[24] Rountree, 84-85.

[25] Dorman, 103. Forrest, William, Historical and Descriptive Sketches in Norfolk and Vicinity (Philadelphia: Lindsay and Blakiston, 1853), 459-460. Turner, Florence Kimberly, Gateway to the New World: A History of Princess Anne County, Virginia 1607-1824 (Easley, South Carolina: Southern Historical Press, Inc, 1984), 57. Mason, G.C. “The Colonial Churches of Norfolk County, Virginia,” William and Mary College Quarterly Historical Magazine, 21:2 series 2 (April 1941).

Pingback: Religious Tolerance/ Intolerance in 17th Century Virginia: Anglicans, Puritans, Catholics, and Quakers – Thorowgood World